The Unfinished Gesture

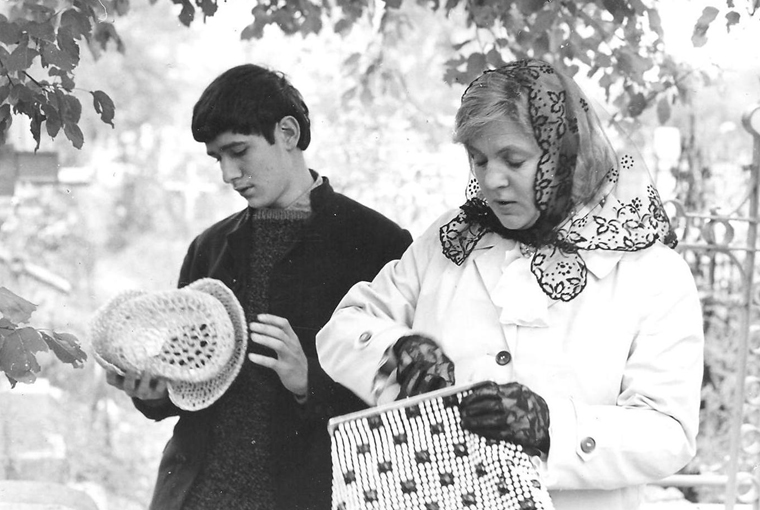

Kira Muratova’s Long Farewells (Dolgie provody, 1971)

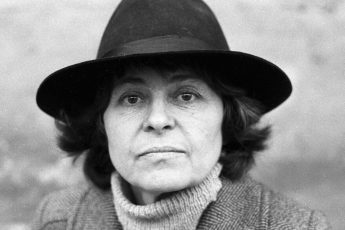

Vol. 98 (October 2019) by Eugénie Zvonkine

In her second feature with sole director’s credit, Long Farewells (1971), Kira Muratova offers a cinematographic method based on the unfinished. Previously, I have compared the film to a ‘hesitation waltz’1 between a mother and her son, the latter hesitant to leave home, the former trying to stop him, only to give up in the end. It’s worth remarking that most expectations in the narration are dashed: the love story between Evgenia Vassilievna (the mother, wonderfully played by Zinaida Sharko) and Nikolay, whom she meets at a friend’s place, is doomed; the telephone call between Masha and Sasha, who is in love with her, won’t take place either, because he asks his friend to speak on his behalf. These ‘disappointments’ orchestrated by the filmmaker prepare us for the final plot twist: the adolescent’s promised departure doesn’t occur — Sasha decides not to leave his mother after all.

But it is not only the characters and their paths that suffer from incompleteness. All aspects of the film’s diegesis are caught up in it. Objects won’t fit and gestures struggle for completion. Thus, the ink pen used by Evgenia Vassilievna to write a telegram to her ex-husband rolls off the post office desk several times when she tries to put it down. This entire scene is significant because the heroine attempts several openings – “Leave us alone”, “Please…”, “If you don’t…” – before giving up on the very idea of sending a telegram. Another action incomplete. Before she gives up, the audience sees clearly (in a close up which reveals the very texture of the page) her hesitant hand, the words traced by a trembling pencil, before they are crumpled up and thrown out of frame. In the same way, when Sasha tries to jump over a fence during a sports class, the editor replays the jump several times, as if to stop him from succeeding.

One moment at the beginning of the film illustrates this difficulty of finishing a movement, although this scene may seem unremarkable. In the flower shop, Sasha turns while holding onto a beam above his head. Just when this gesture is about to end, we jump to a repeat cut (no doubt shot at the same time) which shows the same action from the beginning. Kira Muratova often plays around in this film with starting an action and then interrupting it just before it has ended. She does the same thing when she shows two young women walking around the flower shop. The two shots of Sasha turning are accompanied by a particular extradiegetic music which accentuates this “stuttering”. The music has trouble coming to an end too: Muratova opts for a melody played on a piano which is slightly out of tune and the melodic line of which only rarely arrives at resolution.2 It’s a repetitive melody, duplicated in different keys. In the above-mentioned passage, the music continues for several minutes before vanishing as if it were dissolving into the soundtrack without reaching a melodic resolution.

Thus it is in the editing of the film that the essential links are made between the feeling of incompleteness of the gestures, the words and the thoughts of the protagonists. This is particularly apparent during the transition between the sequences, because almost none of them come neatly to an end. They are mostly interrupted in mid-flight. The end of the sequence in the flower shop which opens the film is thus interrupted with the image of one of the young girls turning towards her friend. The camera swings away in a rapid pan from left to right, following her gaze, before the shot is suddenly interrupted and we cut to a shot of Sasha, already at the cemetery. We’ve thus closed one sequence and arrived at the next (which takes place later and in another place) while the spectator believes they are witnessing a match cut. Even when the editing is less abrupt, the sensation of incompletion remains: at the end of the bus scene, when the mother and son argue over an invitation to visit their friends’ place that Sasha doesn’t want to accept, the camera leaves the two of them to follow three silhouettes, visible from the window of the bus, running in the field. Who are they? We’ll never know. The music is interrupted between two notes and the shot is suddenly cut. We find ourselves at the dacha where the next scene will take place. It’s as though the director wanted to place a mystery scene at the end of the sequence, a shot which questions the spectator without allowing them a clear response to the questions asked, to force them to experience the sensation of a missing explanation for a mystery that they encounter without being able to resolve it.

This brings us back to a remark made in passing by Kira Muratova herself in the role of Valentina Ivanova in Brief Encounters (1967), which gives us a valuable insight into her work:

If you watch a film or you read a book, everyone in it is so beautiful. Their feelings, their actions are so well thought-out, so consistent. Even when they suffer, everything is logical and coherent. We understand the reasons and the consequences. There is a beginning, a middle and an end. But here, everything is vague and shapeless.

Muratova thus proposes us a world not to be understood in Cartesian terms but centered upon the unresolved mystery of existence, on its incompleteness. This reminds us of a speech by Maurice Merleau-Ponty about incompleteness as an unavoidable criterion of the world: “The world and reason aren’t a problem; let’s say, if we wish to, that they are mysterious, but that this mystery defines them. There’s no question of clearing them up with a ‘solution’, it is beyond solutions”,3 and later on, “My life escapes me on every side,” because our awareness of life is defined by the “unfinished”4.

Therefore, “Real philosophy is to relearn to see the world, and in this way the telling of a story can represent the world with as much ‘depth’ as a philosophy essay”.5 This is the program that the filmmaker seems to have assigned to herself, and to us. In effect, we are shocked when the trajectory of a gesture is interrupted. As the object of extreme attention from the filmmaker, these unfulfilled gestures carry the idea of the process being more important than the result. They tell us that we should relearn to see the world around us with, at its central focus, all that is usually set aside in traditional fiction.

In the same way, the filmmaker puts traces of the film’s creation into the film by introducing several shots of the same scene and refusing to settle on one (another patent example of this procedure is the confrontation sequence between Evgenia Vassilievna and her boss about the invitation of an external translator). Kira Muratova could have taken part in an “association for the safeguarding of rushes and the rehabilitation of unused footage” that Jean-François Lyotard wished for in Acinema. She even claimed to have a true passion for outtakes and often kept them in the montage, because they each appealed to her for different reasons.6

The film itself is thus presented as an unfinished gesture, the intention of which is not to give us a clear and organized picture of the world, nor to recount a story that is “flawless”, but to offer us an experience of vision and perception that preserves its share of mystery and irresolution until the end.

Translated from French into English by Colette de Castro

References

-

1.Eugénie Zvonkine, Kira Mouratova, un cinéma de la dissonance, éd. L’Âge d’Homme, Lausanne, 2012, p.229.

-

2.To learn about the creation of this music, read the interview with the music’s composer Oleg Karavaichuk: Oleg Karavajčuk, «Porjadok not», Iskusstvo Kino, N° 2 from 1995, p.107-111.

-

3.Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la perception, éd. La Librairie Gallimard, NRF, coll. Collection Bibliothèque des idées, Paris, 1945, p.xvi.

-

4.Maurice Merleau-Ponty, op.cit., p.382.

-

5.Maurice Merleau-Ponty, op.cit., p. xvi.

-

6.Kira Mouratova, interview with the author, Odessa, April 13, 2009.

Leave a Comment