There Are No Perfect Places for Living

Lidia Duda’s Forest (Las, 2024)

Vol. 140 (December 2023) by Jack Page

On its surface, Forest begins as a documentary that details the daily mundane routine of a small family secluded in the woods of the Polish-Belarusian border. As the film develops, it depicts a courageous family that are prepared to risk everything in order to help refugees in need. However, their humanitarian tendencies introduce additional complications and their safehouse cannot protect them from the inherent grief and guilt they will face as a result of the government’s treatment of migrants.

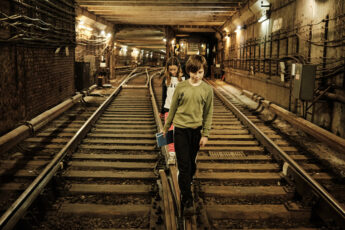

Settled in the very heart of the forest, the roles of the resilient household extend beyond that of a typical nuclear family. They are also farmers, beekeepers, gardeners, hunters, foragers, and protectors. They find an innate pleasure in nature, whether it’s frolicking naked in the fresh snowfall of winter or crowding around the camera trap like a television set to watch footage of elks. What seems at first to be a carefree and resourceful existence is swiftly interrupted by murmurings of paranoia and surveillance. In the dead of night, they leave the safety of the home, equipped with medical supplies and food. Gazing out into the darkness with his binoculars the father shouts, “Do you need help? What are your names?” The mother is convinced she sees people hiding in the trees and during their patrols they begin to track human footprints. The insidious reveal that the family aren’t spying on strangers, but searching for refugees to aid them in their journey is achieved with an engaging level of tension. Scattered throughout the film, there are heavily stylized sequences wherein the camera steadily crawls through the leafy ground of the forest. Backlit by an amber torch, the creeping frame pulls the spectator into the foliage and eerie shadows. The tracking shot’s momentum is both hypnotic and menacing, and the soft focus prevents the viewer from seeing what lies ahead. It is the closest experience in which the spectator can align their point of view with that of the refugee: it’s frightening, it’s disorientating, and it’s the unknown. With each repetition, these sequences become longer in duration and the mystery of the abstract shapes and sensory illusion is explained. These flashbacks allude to an event in which the family were able to aid a group of refugees with shelter, light, water, food, and guidance.

When the family clean up the remnants of a recently abandoned campsite, they investigate some of the artifacts at home. Some sodden paperwork is a collection of maps, school degrees, and employment letters, all important documents in relocating and finding housing in a new country. There are close-ups of ID photos, regional stamps and religious jewelry as the family hypothesize the faith, race, and failed future of the individual. The harsh reality of this imagined persona is too much for the mother, who claims, “Poland only welcomes those with white skin” as she turns off camera to weep. There are many pivotal dialogs between the parents in which they contemplate their “pseudo-paradise”. In the kitchen, they deliberate if – given the choice – they would decide to move out to the forest knowing what they know now. The mother particularly seems guilt-ridden, to the extent she refuses to drink a cup of coffee as she is aware that the refugees can’t afford such luxuries. How can they celebrate the small, everyday victories of life on the farm when there are people dying in the forest? In a very honest and intimate scene, the parents begin to debate the consequences of having children and how that has impacted their ability to help the refugees as well as taken a toll on their own relationship: “it’s either the kids or the refugees”.

In the film’s closing scenes, there is a montage of refugees caught by the camera traps set up by the family. The camera footage shows glimpses of exhausted and disheveled people, traipsing through the barren wilderness. With their torn clothes, muddied faces, and weather-worn skin, it is clear that their ordeal is far from over. Some individuals lack any kind of supplies and clutch at their own shoulders for warmth as they pass by the frame. These static shots are juxtaposed against the film’s more stylized final sequence, in which the camera soars above the treetops of the forest. Panning high amongst the swaying branches, the extended duration of the shot amplifies the vastness of the woods as if the land stretches on forever. The only accompanying audio is the chilling sound of the howling wind, further establishing the grueling conditions of the setting and the brutal expanse that the refugees must inhabit as they travel wearily through.

Lidia Duda’s seemingly formulaic yet endearing family portrait transforms into something more sinister as it unveils Europe’s refugee crisis between the Polish-Belarusian border. In capturing the daily existence of a local case study, the documentary is open to explore the controversial, global conversation around migrants and the country’s own accountability. Through the somber discussions between the mother and father, whose quiet existence in the forest has been unexpectedly disrupted by the struggles of the neighboring refugees, the director aims to expose the government’s responsibility (or lack thereof) for these civilian consequences. The bleak conclusion of Forest is an astute reminder of the tragedies that already occurred, but it also seeks to look towards the future and asks the viewer what can be done to change the course of the sad European migration tale.

Leave a Comment