We met Georgian filmmaker Tato Kotetishvili during the Golden Apricot Film Festival in Yerevan (13–20 July). Kotetishvili discusses the particular style and directing approach of his debut feature, and the difficult political circumstances he and his fellow Georgian filmmakers are facing.

While watching your film I wondered about your cinematic influences. What influences from Georgian cinema have you drawn on in this film in particular?

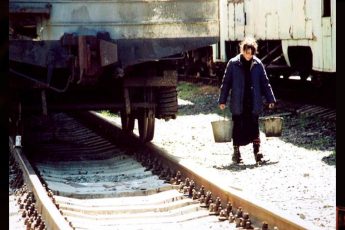

Everything influences me – Georgian cinema in general. My uncle was a director, and Otar Iosseliani also influences me. But it’s hard to say exactly what influences me. Some people say my style somehow reminds them of Paradjanov, but I’m not sure – maybe it’s the flea market atmosphere. In Armenia, no one mentioned Paradjanov’s influence, but in Germany, they were saying it. I think of my film as a kind of collage. Visually, it’s very distinct. It started from a desire to shoot in these locations – scrapyards – which are like collages themselves. I’m interested in architecture and in people who renovate small parts of their homes. The story came from this idea of refurbishing. Each element of the film is part of a collage; the story works as a collage of different stories. I like the idea of using old things to make something new.

Tbilisi is also traditionally a city of trade, of merchants – there’s the history of the caravanserai. That idea of trade is also present in your film: people refurbishing waste. Paradjanov had this idea that objects could have a kind of transformational role – for him, objects were much more than props. How did you work with all these objects?

We chose the objects instinctively. Objects hold stories. They gave us the story. Like the old lady who sells toys in her apartment – those toys and objects had a history. My father is actually a designer and has a lot of objects like that. I grew up in a flea market atmosphere, surrounded by collections. Objects also give actors something to talk about. That scene where the old lady is asked about the toy – “Does it make a sound?” – and she replies, “No, it doesn’t make a sound.” She’s talking about the object, not reciting lines. That’s something I liked.

So would you say it’s about found objects? Or did you work closely with a set designer?

We had a set designer, but many things were done on location. We chose a lot of locations that already had many objects. Then we took some things out or added what we needed. Some places already had a great atmosphere. We worked with a documentary approach – we created from what we observed.

That neon cross – is it referencing something spiritual or religious? I was reminded of Power Trip, the 2001 documentary about the electricity crisis in Tbilisi. In that film, electricity becomes a metaphor for the energy of the city and its political situation.

I don’t know… It’s however you want to see it. It’s open to interpretation. When I was writing the script, we had to explain everything, but now I don’t want to. I think explaining would make it worse, you know? The most important thing is to create a certain atmosphere.

We’ve talked about waste and objects – maybe we can turn to people now. You mentioned that the characters were played by real people, and that you improvised a lot. Can you tell us more about your actors and non-actors?

All of them were first-time actors, except for Bart’s crush – but she had only been an extra before. Casting took the most time. We did small rehearsal tests, like screen tests, to see if they could improvise and feel free in front of the camera. Once I found them, I spent time getting to know them. Sometimes they surprised me by doing things I didn’t expect – and that was great. We didn’t do multiple takes. Even if we repeated a scene, it was different each time. We had scripted dialogues as a backup plan but I didn’t use them much. The actors improvised perfectly. We shot chronologically, to understand how the story would evolve. The dialogue came out of the personalities. For example, Bart read the script but forgot it immediately, which was good for me because he could act with the flow. Another example – Gonga really broke his hand during the shoot, so instead of waiting for him to take one month off, we waited several days for him to recover and incorporated the broken hand into the story, and continued shooting.

The people you chose – they all seem to reflect a kind of marginal status. And there’s a reflection on transgender identity in the film as well.

The story is set on the margins, in the suburbs. The people selling things from their homes are also, in a way, marginal. All the characters are in need of money. The transgender theme came through Bart. When I found him, I was fascinated by his character – and by the fact that he’s a biological woman. At first, I wanted to shoot him as a biological man. But when I learned more about him, I started thinking about integrating it into the story. He inspired me. I asked if he was okay with it, and he was very happy with the suggestion. I didn’t want to push it too much though.

I read about the so-called “Russian law” in Georgia that shut down LGBTQ+ NGOs and community spaces. How would you compare the situation for transgender people in Georgia to other places?

I don’t really know about Russia, but I don’t think the situation there is good. In Georgia, the “foreign agent law” does not only aim at LGBTQ+ NGOs – it targets any NGO that receives foreign funding. It’s aimed at civil society organizations and independent media as well as film companies who are getting funds from Europe to make films. The law makes it harder for NGOs to help citizens. There is a so-called anti-LGBTQ+ propaganda law as well, which directly threatens LGBTQ+ people. They prohibited any medical intervention for gender transition as well as public demonstrations supporting LGBTQ+ identities. At first, I thought they were just going to introduce the law for the elections so as to cater to conservative voters. But they really enforced it. Bart’s friend, for example – he had a rainbow flag keyring, and some policemen told him to put it away. For transgender people who need help, like medicine, it’s complicated. Bart was worried he wouldn’t be able to get his hormonal medicine anymore – he has to take it every month, otherwise he feels really bad. Many transgender and LGBTQ+ people have left for Brussels, where Bart now lives as well.

I really liked the music in your film. Was it mostly Georgian bands?

Yes, it’s Georgian underground bands. Mainly from the musician VAQO – his tracks run during the end credits and also in the middle of the film. He’s very talented, a multi-style musician. We also used some tracks by Anarekli, Skazz, and Izmir.

Are you working on a new film right now?

I’m slowly thinking and writing – still at the synopsis stage, but I hope to start development soon. Things are a bit slow right now because the Georgian National Film Center isn’t really working. It functions, but we are boycotting it because it’s very pro-government, and the government is pro-Russian, so we don’t apply for funding there. It’s a very chaotic situation. For a co-production, we need Georgian funding to cover at least 70% of the budget – that’s how I got the money for this film, six years ago. I’m hoping something will change. We’ll see what the future brings.

Well, at least you managed to finish this wonderful film…

I was lucky to have all these wonderful people who worked on it. Together we managed to make it to the end despite all the problems that we faced.

Thank you for the interview.

Leave a Comment