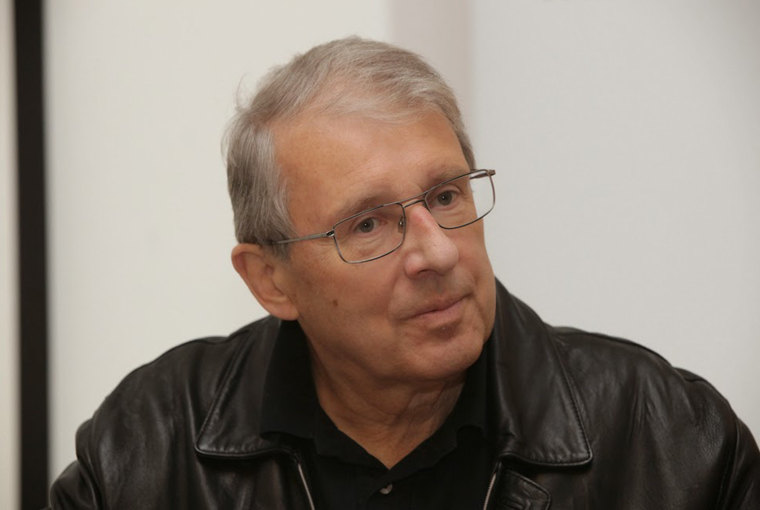

We met with Polish director Ryszard Bugajski to speak about his career, which spans over forty years. Among his most prominent films is “Interrogation”, which tackles the Stalinist period and was entered into the 1990 Festival de Cannes after being banned for nearly a decade. Bugajski, having moved to North America and back, speaks about his beginnings in Poland, his decision to move to the US, common themes in his works, and differences between the Polish film industry and the Hollywood system.

You were born in 1943 in Warsaw, only one year before the Warsaw Uprising, which resulted in the systematic decimation of the local population. It would be very interesting to know…

… how I survived?

Yes.

I barely survived, I must say, because I was – together with my mother and other members of my family – nearly executed by the German firing squads. Fortunately, a huge bomb fell before the wall where we were all lined up, killing the whole firing squad. And that’s how we survived.

Did you stay in Warsaw till the end of the war?

It wasn’t actually in Warsaw but in suburban Warsaw. The place was called Choszczowka and it was one of the most terrible places to be, as both the German and the Soviet fronts met there. My father, who at the time was fighting in the Warsaw Uprising, told my mother to find a safe place there. But it appeared to be the worst “hiding place” one could possibly find.

Once you were old enough to study, you applied to the Lodz Film School. Was it your first choice to go to film school?

No, it wasn’t. At first I wanted to become a musician. I played various instruments. But I wanted to be a rock musician rather than just a musician, so I gave it up as soon as I understood I was not talented enough. Simultaneously, I was also drawing and painting so everybody was convinced I was going to become a painter. Then the time came when I began writing short stories, reportages and some sort of journalistic pieces. Yet, I graduated from high school not knowing what I wanted to do in my life.

So you had done all of this before actually starting college?

Yes, indeed. And when it came to choosing a main subject at the university I applied to the philosophy department. I studied philosophy for quite a while at the Warsaw University where I met many interesting professors including Leszek Kolakowski. However, in my third year, I accidentally went to the movie theater to watch 8 ½ by Federico Fellini and after only fifteen minutes I simply knew I would become a film director. To the horror of my mum, I immediately quit philosophy and applied for film school. I got rejected at first but was admitted in 1969. And that’s how it all started.

Would you say that the years spent on philosophy influenced your films in some way? While watching your works one gets the feeling that it was politics that heavily “stigmatized” your productions.

Certainly philosophy – and especially ethics – influenced my films. Ethics and morality are much more important to me than physics, chemistry or astronomy. I think that the moral choices that people make are way more significant than some laws of science. Studying philosophy provided me with many useful skills: it taught me logical thinking and rigorous discipline. When I write a script or when I work on set I still have the habits of a disciplined philosophy student.

“Interrogation”, “Clearcut”, your Canadian film, “General Nil” or your newest production “The Closed Circuit” share some kind of fascination with physical and psychological torture and how people respond to it. What is it about the whole process of interrogation and torture that interests you so much?

It is very difficult to do a self-analysis and I think it is a better job for critics and viewers. But if I actually look back at my life I can clearly see what really influenced me more than anything: it was my constant struggle with Communism. That system was omnipresent; it was stuck like glue to our everyday lives; it was with us at school, at work, at the theaters and cinemas. So I was in a constant struggle with that invisible mechanism that controlled our lives – perhaps because my nature is the nature of a man who wants to be free at any cost. Physical torture is less interesting to me than psychological torture. It manipulates people by instrumentalizing their fears and weaknesses; skillful interrogators can easily detect such vulnerable points in every human being. I have been through such an interrogation and paradoxically the whole process made me understand myself better.

What were you accused of?

I was not accused of anything. They wanted to make me an informer for the militia because many of such informers became simply too old or did not have access to the artistic milieu of the late 70s. They wanted to recruit new people and I seemed to be a good candidate because I was a promising director at the time. I had connections and I traveled abroad. However, although the whole recruiting process was rather slow and gradual, I resisted it.

So it was not a one-time attempt to make you an informer?

Not at all, the whole process lasted until I left Poland in 1985. Although they understood I would never work for them, they were harassing me in many different ways.

That brings us back to what you said earlier: namely, that you always wanted to be a free man. Was this desire, together with the harassment you experienced in Communist Poland, the main reason behind your decision to leave Poland? And if so, do you feel that working for the American and Canadian film industries granted you that artistic freedom? Or did it actually turn out that producers from the States and Canada have an overbearing authority over aesthetic choices? In the end, you returned to Poland.

Yes, but I returned to Poland when it became a democratic country. It is very difficult to compare the Hollywood system with the film industry in Poland. Back then, all countries of the Communist Bloc had to comply with the totalitarian system at every level of film production. In Hollywood, you can be hired if you are talented, but if you don’t agree with their ideas they can simply fire you. It is a different relationship, which I prefer because it is based on free will on both sides. In Poland there was no free will on at least one side. Perhaps on no side because the people working for the Communist government, the police, were also not free in all their actions; they were told what to do. Of course, political pressure can be equally damaging as financial pressure but it is up to an individual to find a solution. I definitely prefer to cope with the economic pressure than the political one.

Since everybody dreams about working in Hollywood, why did you decide to return to Poland nevertheless?

First of all, I was born in Poland, Polish was – and still is – the language I speak best. The lack of freedom was the reason why I left Poland and once the political system changed, I returned. Of course, it took a while, I did not move back to Poland in 1989 but nearly ten years later. I had my life in Canada, my son went to school there, I had many friends and I could work as a filmmaker. So it was not easy to go back. But maybe had I been offered to make a great Hollywood movie at the time, I wouldn’t have returned.

Your newest film, “The Closed Circuit”, which shows the story of three successful businessmen being completely destroyed by corrupted government officials, just premiered this year. Do you think it would have been possible to make it in Hollywood?

Why not? Similar stories have actually been produced, e.g. under the title of Erin Brockovich. Hollywood also sees a potential in themes that deeply affect human lives and show the injustices of political systems.

Would you like to say a few words about your newest film?

I think that The Closed Circuit would reach a much wider audience if it had not been made in Polish. American viewers hate subtitles and I have known about this for many years. I felt that since the film is about a concrete situation in Poland, it had to be made in Polish. Well, Roman Polanski made his film The Pianist in English although the characters are Polish. He played a kind of a game with viewers who accept certain kinds of conventions. In my film, which is contemporary, it would be a total lie if I had made my Polish characters speak English. I am aware that my film has limited access to American viewers but I hope that those who will watch it will find it compelling.

Thank you for the interview.

Leave a Comment