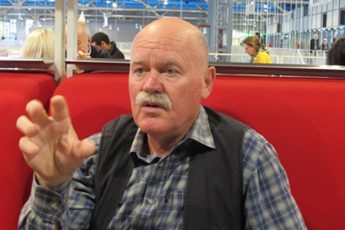

We met Ivan Salatić at the Thessaloniki International Film Festival, where he presented his debut feature about a young woman and her hometown. Salatić speaks about the idea behind the film, the filmmaking process, and the challenge of making films in a small country.

The story of the family in your debut film is set against the backdrop of the closing of the main shipyard in Herceg Novi (Montenegro). How much of this story is based on autobiographical details and your personal experience?

The film starts on the open sea. Through an elliptical narrative we follow Sanja and her return home, where the story branches out to describe fragments of her family’s life and more precisely, that of several families in this coastal town, while in the background the shipyard is closing down. The town is on Montenegro’s coast. I know it very well because I grew up there, and the reason for choosing the shipyard as the place around which the characters are built, is because my father had worked there his entire life. This place was an integral part of the landscape during my childhood. When we were shooting the film, the remaining piece of the shipyard, the Mali Dok (Small dock) was being shipped away, and its disappearance meant much more for me than the failure of the economic system. I thought about how my father would have felt if he had witnessed the departure of the small dock at night. My father’s relationship with the shipyard was almost equal to his feelings toward the family. For the character in the film (the unemployed man who wonders around like a ghost), the shipyard doesn’t only represent a job, but the feeling of dignity, and belonging to a community. Socialism taught people that society was above the family or at least on the same level as the family. It was society’s role to take care of everyone. That was a utopian idea, so the very departure of the docks from this depleted shipyard is a kind of a metaphor for the disappearance of this utopian project. As someone who was born as that idea was starting to deplete, I wanted to understand and make a film about ordinary people – those people who had built it.

The narrative is very carefully constructed, and as the film unfolds, certain information and parts of the story are slowly revealed, and we discover the characters’ story little by little. You also authored the script. Could you tell us something about your dramaturgical choices?

The narrative was primarily constructed during the process of filming. The script itself was subject to changes during the entire shooting. That’s one of the things which I find normal, first of all, because I consider that you should only be faithful to the script in terms of its essence and the reasons why it was written. In the script, I fixed certain things concerning the structure of the film, the form, the way of shooting, etc., and the rest that is more or less literary, or related to the narrative, I let undergo changes. The reason for this is that I believe that each film establishes its rules mostly during filming and editing. I wanted to be prepared to recognize and appropriate elements which occur during filming, even if they are beyond the scope of my ideas and concepts as written in the script. In the narrative sense, I wanted that the relations between the characters remain open and be shown in ellipses, because it seems to me that in this way we are closer to the realism and intimacy of family life.

Your film portrays a dire economic situation and the necessity to migrate elsewhere. Meanwhile, all of the characters in your film are somehow connected to the sea. How important was this element and how much does it reflect the reality of the social and economic condition of Montenegrin society?

You have the Night, first of all, reflects this feeling, which seems to me occupies a large part of my generation, who had lived through the 1990s. It is a feeling of uncertainty, indeterminacy, non-belonging. Permanently waiting for a better time to act and dreaming about going somewhere else… It’s wandering through non-places. Furthermore, the film includes my attempt to render the picture more prevalent with the characters I mentioned earlier, which represent the older generation, who did not cope with this new reality after the breakup of socialism. It was important for me to take up my stance towards this generation. The images you see in the film are trying to convey, not only the materiality and the economic situation of a particular moment, but also the materiality of transience, decay, wasted ideas, as well as the desire and the necessity to imagine another tomorrow.

In the final scene, the old man tells Sanja’s brother, Luka: “I have nothing and you have the night.” This phrase, as well as being the title of your film, seems to encapsulate the experience of this family, community and perhaps even of Montenegrin society.

The scene at the end in which the old man pronounces the monologue was shot last. That monologue was written a few hours before we shot this scene and given to the actor who plays the old man, Momo. It was necessary that I shoot all the previous scenes and spaces with him before so that I would know exactly what his character would say to Luka, Sanja’s brother. This says something about the organic way I want to make films. The line “you have the night” brings up all of the fears, anxieties, and monsters people carry around, but the night is also the destination of those who have to hide, find shelter and make plans for the future. “You have the night” is like some sort of trigger for Luka, who must come to self-understanding, liberate himself, become autonomous, survive… Each of these things would be a correct description of what I had in mind when I thought of Luka entering a dark forest in the end. Anyway, I think that I wanted these words at the end of the movie to resonate more broadly because in the end, it seems to me that as a society today, we are all faced with that night in which everything seems impossible and possible.

Is the dismantling of the shipyard in the film a symbolical way of dealing with the remains of ideals and ideas of former Yugoslavia?

I think it is more correct to say that the dismantling is a metaphor, not a symbol – a metaphor for the breakdown of the system and values of the socialist project. The end of this particular shipyard is a metaphor for the fate of objects throughout former Yugoslavia. It is not taken only as a fact which happens on the coast of Montenegro (although it is certainly a document of that particular event), but it is also used as a metaphor for a larger process. I don’t want to sound nostalgic, nor could I be, considering I only became self-conscious at a moment when the disintegration had already started. Here, I was primarily dealing with the feelings of people who have been deceived, with the porosity of their memory, the ideal, the disappearance of things, and with a particular feeling that I share with most people from my generation.

The film uses archival black and white footage from the inauguration of the Bijela Shipyard. Could you please explain how you work with archival footage? How does the footage appear in the film in connection to the old man?

From the start, I knew I wanted to have archival footage as a document which would actualize the reasons I was dealing with. In this archival footage, we see the coming of the big dock and the moment in which the shipyard was given its name. We see these people and every word is superfluous. No need to convince anyone, the images speak for themselves. We see the shipyard full of people, they are proud and dignified, and everyone is dressed in their best attire, ready to build for the future. It was important for me that at one point in the film I slip into the past and be close to the experience of this past through images. In formal terms, the archival footage is inserted as a dream of the old man, but as film material, it is present, above all, as an anchor.

Lastly, could you please tell us about the challenges of being a young filmmaker in a small film producing country? How did you secure funding for the film?

It is important that the practice of supporting films continues, and that people are educated in that direction. Until now, this was the role of the Ministry of Culture, which financed most of my film, as it was a project which had obtained the support at the last feature film funding call. But Montenegro recently founded a Film Center which will now assume the responsibility of supporting film projects, having joined Eurimages. It’s not easy to be present within a wider cinema industry and be visible, especially if you come from a small country like Montenegro. There are various problems in education, staff, distribution of films, etc. I think that in small countries, the state plays a key role in allocating funding for cinema.

Leave a Comment