Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi on their Armenian Films

Vol. 69 (November 2016) by Moritz Pfeifer

We met with Italian artists Yervant Gianikian and Angela Ricci Lucchi at the Centre Pompidou during a 2015 retrospective of their films and installations. The artist duo speak about their preoccupation with and interest in the Armenian genocide, their artistic choices in dealing with it, and the process of remembering more generally.

Let’s talk about Armenia and about the films that you’ve made regarding the memory of the genocide. When did you visit Armenia for the first time? What pushed you to go and what exactly were you looking for?

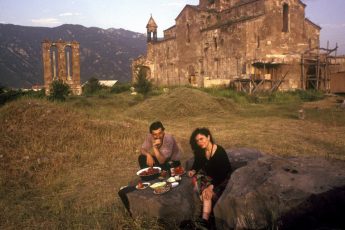

YG: The first time we went was in 1987. I had been invited by the union of Armenian filmmakers to “visit the Motherland and be inspired by it.” This is what was written in the letter I received. I had been requesting to go for years to look for the roots of the Armenian people’s history. Angela joined me with Italian actor Walter Chiari. He had read a few pages of my father’s memoirs on the genocide, on the massacre of 1915.

ARL: Why did your father have these pages on the genocide?

YG: Starting in the 1920s, my father began keeping a diary, writing down everything he could remember about the genocide. Thousands upon thousands of pages that I couldn’t read.

Your father didn’t share these writings with you?

YG: No, they were in Armenian and he didn’t want to share them. Then, in 1976, he left for his country of birth, crossing Eastern Turkey by foot. There he found his house destroyed. There is a narration of this long march, Return to Khodorciur. An Armenian Diary, which will be shown here [at the 2015 Centre Pompidou retrospective]. As regards us, we haven’t found the documents we were looking for: we’re still looking for the images of the genocide. In reality, we know where to find the filmed material, but the real material is the archive of my father’s memory. The proof is in the memoir he wrote.

In “Return to Khodorciur” there is a series of long sequences which focus on your father reading. It’s one of the rare films in which you left some space for words…

YG: …for words that are read and spoken and for that which hasn’t been said and read, because the rest is that which we will read of these thousands of pages. My father was one of the few survivors. Out of one and a half million people he saved himself and he immediately went on to write, keeping a broad view of the history and memory of the Armenian people. We filmed around this subject for a long time and went to the sites of the massacre even before 1987.

So when was the first trip?

YG: In 1979. My father went in ’76 and we left for Turkey in ’79. He told me: “Look for my father’s grave.” He had found his mother’s grave; I didn’t find his father’s. It’s our biography that is involved, that pushed us to undertake trips that were, at times, dangerous.

Where did you find the images for “Men, Years, Life“? How, in detail, was this work constructed? The material that it is comprised of is very heterogeneous: alongside images of the czarist army there are images that go back to the period immediately after the 1917 Revolution. What is the relation between the exodus of the Armenian people and the genocide?

YG: I have to say that this material continues to be at the center of our research. It’s a work in progress. It is work that isn’t finished, that we haven’t abandoned because there are still many things that need to be said. We found the material over the years, during our travels. As I said, we passed through Armenia, Russia. Some friends were of great help to us; many of the archives we wanted to access were closed. We returned over and over again to the same places, where we thought these archives were located, like, for example, Moscow. When possible, we would go out to make other films and with every expedition we found new material on the Russians. We don’t want to produce work of a nationalistic type. That which interested us and continues to interest us is the reconstruction of the context in which this event came to pass. This is why we chose images from the czarist period, from the Communist revolution, e.g. of the lake of Sevan, where Mandelstam had been and where he probably met and got to know the people that can be seen in the film.

…like a sort of window that looks out onto a preceding moment in history. Let’s turn to the music: why did you choose the Stabat Mater by Pergolesi?

ARL: We really love Pergolesi. It’s beautiful music and for the film we chose a particular recording, sung by a soprano who died young and had a wonderful voice. It’s a requiem, and this requiem is for the Armenians, for the Armenian people.

YG: We’ve been criticized for the use of this music.

Because it lends the images an extremely lyrical tone?

ARL: It was important that this tragedy should be sung by a female voice. It’s the tragedy of an entire century, not just of the Armenians.

YG: Let me reiterate, we put this film together during the fall of the Soviet block. We’ve always operated around boundaries, on the borders of wars and it wasn’t the only time. It was the first time with Armenia, but then it happened again in ex-Yugoslavia. It’s the repetition of a historical moment. The relationship between the Russians, the Armenians, the Caucasus, Mandelstam, the people we met is the basis of Uomini, anni, vita [Men, Years, Life]. Among the people we met there were Nina Berberova and Ida Nappelbaum. When I was in Armenia in 1989, Nina Berberova was going to Leningrad to see Ida Nappelbaum, a dear friend of hers. Angela filmed her during a visit to Milan. On that occasion she signed her book Il Corsivo è mio [The Italics Are Mine], Nina Berberian. She had seen her father perform in a propaganda film during the time in which he lived in Berlin. Effectively, it was all very much linked. As was the incursion of the czarist army in Turkey: the genocide had already taken place because that was in the spring of 1916.

Let’s return to “Return to Khodorciur. An Armenian Diary”. The title of the film contains the word ‘return’. How much value do you place on it?

YG: For us, it’s a personal return. A return to history and not only to the history of the Armenian people. It is a return to the violence that marked the twentieth century. We don’t want to talk exclusively about the Armenians. We’ve addressed the gypsies, the Jews, the refugees… In our latest work Où en êtes-vous, Yervant Gianikian & Angela Ricci Lucchi? [Where are you, Yervant Gianikian & Angela Ricci Lucchi?] commissioned by the Centre Pompidou, there is a little section filmed by us that shows some girls and old refugee women in Turkey. Those old ladies, who at the time of filming were 100 years old, had seen the genocide. They spoke Aramaic. The word ‘return’ is our word because we continuously work with archives: ours is a continuous return to history.

ARL: A return to history, which repeats itself.

“Return to Khodorciur” was made based on images that you yourselves filmed. With regard to historical evidence, what role, what status does the image have relating to the word?

YG: It has the status of a discovery, of that which we discovered in the moment. As I already said before, the proof of the genocide was very close, my father was the proof. However, the images show the places. There are some fragments of the country that my father traversed during his long march, some aerial views. The city of Erzurum for example. My father passed by where the czarist army arrived in 1916. We wanted to see, to reconstruct a part of the path he took during the genocide. He went down that road with 10,000 other people from his country. It’s a map. It’s an obsession that accompanies us and that hasn’t ended. Some elements return continuously. Amongst the material that we found, there is a frame which we’ve never used. Only one, of a naked boy on a street, still alive, surrounded by ragged men walking. This minuscule particle represents to us all the material on which we’ve worked. But we didn’t want to show it, to use it as photography.

Memory always operates in the present. It is constructed in passing, in this continuous returning…

YG: Yes, ours is a continuous returning. In Return to Khodorciur. An Armenian Diary my father does nothing other than return to the sites of memory. Even today it’s like that. The film is currently located in San Lazzaro degli armeni [St. Lazarus of the Armenians] in Venice. It’s as if it had returned home. On the top floor of the monastery that is located on the island, there is a 17-meter-long role of Angela’s. My father told Angela Armenian fables. The role is being shown at the Venice Biennale and this work, alongside that of other artists of the diaspora, won the Golden Lion. Since then, since the 1970s until today, we haven’t stopped engaging with this story. We’re still captivated by it.

On one side stands the film in which your father recounts his story by reading what he wrote, on the other, the drawing, the visual transcription of a verbal exchange. Transmission appears to be at the center of your work.

YG: Earlier we were talking about Erzurum and this fragment of the czarist army arriving after having overcome the mountains, the battles. In an old pocket dictionary that belonged to my father, a dictionary in five, six languages (Hebrew, Greek, Assyrian, Turkish, Armenian…), there was a newspaper cutout from 1916 that reported on the czarist army’s entry into Erzurum. He had kept it. I still have this page and this dictionary. The fables that Angela drew are derived from the audiotapes that my dad recorded and sent to us with an Italian translation.

ARL: I had to transcribe them all before drawing upon them. And thus, many of the pages of his memoirs are read out, are oral.

YG: We have more than one hundred tapes… a hundred times one and a half hours makes 150 hours.

So much of this material is oral.

YG: Definitely, it’s oral.

Was it his favored format?

YG: No, his favored format was writing. And he read that which he wrote.

What do the fables talk about? How did this move towards drawing, towards watercolors come about?

ARL: The fables tell very striking stories, very cruel ones. But the world was like that. They are full of images, they’re all images. For me it was a natural move, they came to me spontaneously. With such a long role, working with watercolors is complicated, because if something gets stained, you have to throw away the whole thing. It was terrifying. Instead, everything came out in a fluid, rapid, easy manner. I was really fascinated by these stories. The role should be read from top to bottom. A friend who came to Venice told me that I truly created a language. I’m currently reading some of Herodotus’ histories, which take place in a part of Greece that was conquered by the Persians. They are reality. Their mentality, their vitality, their cruelty is there in those stories. I wanted to reflect this aspect in the drawings I created. The tenderness is accompanied by great terror.

YG: After all, even our work on the archive is cruel. It’s history that is cruel: the Armenian genocide, the First World War…and in the last film Où en êtes-vous, we show images of Iraq before its destruction.

It is a work on violence. Someone has written that your work is very aestheticized.

ARL: Yes, someone told us: “You create images that are far too beautiful.” They are images in which the ethical is accompanied by the aesthetic. It’s not that the images we work on are beautiful in and of themselves. We are addressing ethics with beautiful images. There was a period in which art also showed very ugly things. One of the accusations, which we faced at the beginning, amongst others, was exactly this fact of creating beautiful images.

YG: As Angela points out, the aesthetic and the ethical go together. Why shouldn’t they?

Of course, but this operation is rather risky.

YG: We have always taken risks. This manner of operating is instinctual for us. We have always worked with images that attracted us and beneath every one of these images runs the river of history. Our films are generally mute, without words. However, we know exactly where we are. We push people to read. When we meet with the public, or in our writings, we say what should be read, where to look for the things that can be seen. Angela keeps a daily diary, an infinite book. Since the 1970s, every day, she notes down the places, the people encountered. For the occasion of this big retrospective, we have started to select a part of our writings, but choosing between Russia, America, and the many European countries that we’ve crossed is very slow-going work. Now we’re working on a new film. It’s a film about Russia.

ARL: They’ll hear about it in the next interview, Yervant. Let’s not give anything away. First one needs to do, then talk.

Thank you for the interview.

Interpreted by Valeria Guazzelli & translated by Camillo de Vivanco

Leave a Comment