Cinematographic Objects

Alexandra Karelina’s Last Words (Poslednie slova, 2020)

Vol. 107 (September 2020) by Anna Doyle

An object is that which exists in front of me; it requires a subject, a consciousness of the object. The object needs attention, or intentions that relate to it, without which the object would not exist. Last Words by Alexandra Karelina is a film about objects, but the spectator is always there to give attention or attach intentions to the object. Watching the film is an experience similar to stepping inside a Joseph Cornell box. If Joseph Cornell created cinematic experiences with the boxes and dioramas he made in the 1940s, in Karelina’s film the memory box is omitted as we enter the room of objects with no mediating frame. By displaying found objects, the filmmaker creates a romantic world for the spectator to enter. Karelina’s film is like a material version of the found footage tradition – a tradition in which Joseph Cornell was a pioneer. When found footage uses film material that has been used in a haphazard manner, here the objects create the thread of the story. They seem to have not been chosen, but appear on the screen randomly and successively.

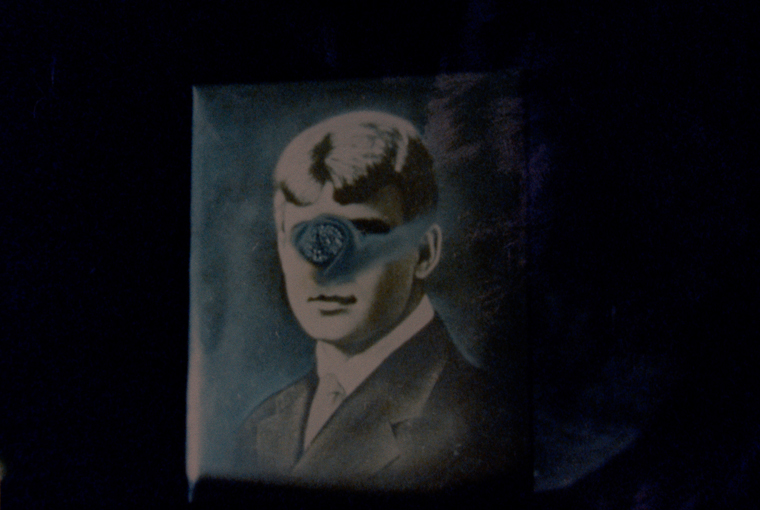

These trinkets are what we find in the corner of a bedroom, on the top of a shelf, things recalled in a long-forgotten throwback of nostalgia: a tiny Santa Claus, candles, Communist badges, necklaces, cards, melting teddy bears, old burned photographs. Karelina speaks of these trinkets as “objects of longing” – they have a relationship with a feeling of belonging that ties in with memory. – Can you long for something that has been found? As Victor Hugo said, “to create is to remember”, and here it is indeed the objects to which our remembrances attach that are writing the story of the film. At the same time images of light fusing erase the narrative line that is threaded. Forgetting is as important as remembering in this film, our nostalgia contains the fragility of images, images that disappear into light as we watch them. Images of candles burning emphasize this feeling of time passing. The voiceover repeats the word “nikogda” in a lyrical way, which means “never” in Russian. The film’s title may refer to this repeated word: “never” is the last word to say when we give in to nostalgia.

The relationship between objects and time is strong. In this film, objects are traces from the past, signs of remembrance. In Sculpting in Time, Andrey Tarkovsky addresses the intricate relationship between objects and time: “No ‘dead’ object – table, chair, glass – taken in a frame in isolation from everything else, can be presented as it were outside passing time, as if from the point of view of an absence of time.”1 Our consciousness, it is suggested, can abstract space when considering an object, it can fragment it and isolate it to come closer to its essence, but it is not possible to abstract time.

If objects seem to take up a large part of the film, much of the film also involves depicting a play on lighting. An intimate light appears, and changes its color and volume. It could be a light cone projected from a reading lamp that adapts itself to room temperature, or it could be a magical light from Pandora’s box. Light and objects collide and oppose each other, creating a dialectical relationship that takes place in a bedroom: the film is indeed divided into two parts, one dedicated to objects and the other to light. The technique of jump cuts, which allows the film to move from one object to the other, the superimposition of images and constant flickering movement is used in the film and resembles a cinematic version of “automatic writing”. The found object brings to mind André Breton’s text on the Crisis of the Object (1936): the objects, found at random, leave a place for interpretation, as well as creating what Eluard calls “a physics of poetry”. Watching Last Words is like a post-Soviet transposition of Breton’s experience with objects. When watching Last Words, we could be reading Breton’s Nadja: “Outdated objects, fragmented, unusable, even incomprehensible, perverse finally”.

It is impossible to save all our objects. We hold on to them, yet they are insignificant and do not have any use for us. That is the incomprehensible idea that lies behind the idea of collecting objects. For Walter Benjamin “the true collector detaches the object from its function”2, the collection process is disinterested. The functional value of the object disappears. For the collector, the arrangement of objects is done in an incomprehensible way, in an almost childlike fashion. It constitutes a renewal of objects that have been defamiliarized and isolated and thereby obtain a new gaze upon them. For Benjamin, the collector is also a “monteur”. The collector and the film editor have never been closer than in Last Words. The jump cuts between objects imitate the act of collecting.

The relationship between an object language and silent cinema is also significant. The close-up shots in the film could also be called object-shots or mute shots. In the history of cinema, the apparition of talkies cancelled out our fascination in front of the object in cinema. Silent cinema is the cinema of the object and the cinema of objects is silent. In the history of cinema, objects have also been important in terms of dramaturgy. As they circulate, meaning and relationships between characters are created. However, when isolated, as in Last Words, they gain a whole other meaning. In his article “The cinematographic object”,3 Jacques Aumont talks about the appearance of objects in film and creates a specific category for the “found-object”, a category through which we could classify Last Words. He opposes it to the “useful-object”, which has a significance in the dramatic action and is further distinct from the “charged-object” that is charged with signification and symbolism. In Karelina’s film, pure attention is given to objects, which are stripped of any sort of theatrical or dramatic meaning. Karelina also creates a way of relating to objects outside of a museal gaze. However, these objects are not linked to a tradition of any kind, nor do they seem to symbolize anything specific. They are charged with a feeling of belonging and are like traces of time eternalizing. They have created a language of their own that cannot be translated. In Last Words, cinema can give life to the inanimate: it eternalizes the successive and the flickering, giving us a heightened consciousness of the intimate and nostalgic world of objects.

References

- 1.Tarkovski, Sculpting in time, Cahiers du Cinéma, Paris, 1989, p. 64.

- 2.Walter Benjamin, Paris, capitale du XIXe siècle. Le livre des passages, Paris, Cerf, 1989, p. 224.

- 3.Jacques Aumont, L’objet cinématographique et la chose filmique , Cinémas, Volume 14, Numéro 1, Automne 2003, pp. 179–203.

Leave a Comment