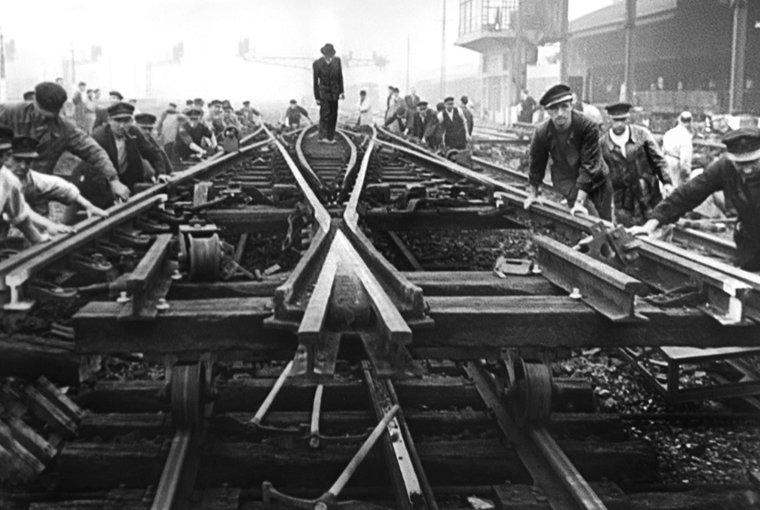

Early cinema was captivated by the train from its very beginnings. In 1896 the Lumière brothers’ L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat offered the first cinematic actuality of a locomotive in motion and notoriously provoked panic among audiences unaccustomed to on-screen forward movement. Almost immediately, filmmakers strapped cameras to engine fronts in the “phantom ride” genre, turning the train into a moving vantage point that both thrilled and disoriented viewers. The camera perched on a locomotive foregrounded motion itself, inaugurating cinema’s core illusion: simulated travel through time and space. By the 1920s, avant-gardists seized on trains’ rhythmic mechanics.

In Joris Ivens’ The Bridge (De Brug, 1928), the Koningshaven bridge in Rotterdam becomes a composition of shapes, movements, contrasts, and rhythms as steam engines and hydraulics are dissected into abstract visuals. The human figure appears as a tiny speck against steel girders. As a driving force of the Second Industrial Revolution, the train also symbolized an anti-humanist inclination in which technological progress and machines eclipse individual agency.

In city symphonies like Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (Berlin – Die Sinfonie der Großstadt, 1927) and Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (Lyudyna z kinoaparatom, 1929), trains serve as emblems of dynamism, rupture, and the dialectics of modernity. Sequences of speeding trains are accelerated through fast-motion montage, symbolizing rapid industrialization and the Soviet project of social transformation. For thinkers like Siegfried Kracauer, trains embodied the promise and peril of mechanization. Vertov’s self-reflexive shots of cameras atop rails, or tunnels swallowing the lens, transformed this critique into poetic montage, in which cinema’s dual role as observer and actor becomes apparent.

A good century after city symphonies and phantom rides explored trains as carriers of modern experience, Polish filmmaker Maciej J. Drygas certainly taps into charged historical legacy in his latest found-footage film Trains, most of which draws on archival material that falls into that period. The film opens on Franz Kafka’s foreboding words, “There is plenty of hope. An infinite amount of hope. But not for us,” setting a tone of longing and uncertainty. No voice-over or interviews interrupt the images and Drygas relies on post-synchronized rumble of wheels and clipping rhythms (the sound design is by Saulius Urbanavićius). The project spanned ten years of research and editing. Drawing on nearly one hundred archives and selecting material from 46 collections across Europe and beyond, he constructs a panorama that begins in early locomotive workshops and stretches through the First World War, the interwar era’s luxury travel, the horrors of the Holocaust, and postwar reconstruction.

Trains unfolds as a pure cinema of movement: shots range from ultra-long takes of endless tracks to rapid cuts between steam whistles, coupling rods, and station crowds. Drygas has said he “didn’t want just to do a movie about the history of locomotives.”1 Yet Trains often reads as little more than a linear procession of archives. Soviet montage theory taught that meaning emerges from the collision of independent shots, a thesis encountering its antithesis to produce a synthesis of ideas. Drygas, by contrast, orders his footage almost strictly chronologically, offering no arrangement of his footage that could interrogate the machinery he presents. Even the Holocaust images, the piled corpses of concentration camps prisoners, appear as one more archival clip rather than as the culmination of an argument about mechanized death and human responsibility.

The Kafka quote, importantly phrased in the present tense, promises an invitation to draw parallels between past and present crises, whether that means questioning how trains became tools of genocide, or contemplating how new technologies today might again remap power and alienation. But it is a promise the film does not meet. In the end, Trains may be a remarkable panorama of twentieth-century rail travel, but in its exhaustive quest for footage it loses track of where the journey leads.

- Macnab, G. (2024, November 19). IDFA International Competition: Trains by Maciej J. Drygas. Business Doc Europe. https://businessdoceurope.com/idfa-international-competition-trains-by-maciej-j-drygas/ ↩︎

Leave a Comment