A Slow Observation of Horror

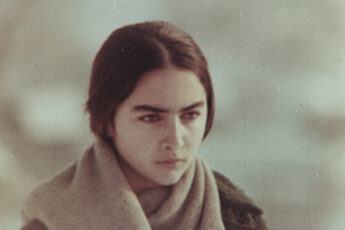

Olha Zhurba’s Songs of Slow Burning Earth (2025)

Vol. 154 (April 2025) by Anna Doyle

Is it war?” a voice asks on an emergency hotline as the film opens. The answer is left hovering – yes, it looks like it. Yet in Olha Zhurba’s gut-wrenching documentary Songs of Slow Burning Earth, war is not always explicitly named. It is not explained or justified; instead, it permeates the images almost invisibly, demanding that the spectator piece together the various experiences Ukrainians have gone through over the course of the past decade. Zhurba privileges showing over telling, creating a rhetoric of observation that immerses the viewer in the harrowing textures of the ordinary under invasion, and the pervasive and constant threat of loss.

The film resists images of the battlefield, focusing instead on the slow violence endured by civilians: by children and the elderly, workers in factories, doctors, teachers, students, grieving fathers and mothers. The destruction unfolds insidiously, seeping into every gesture. After two years of filming across the country, Zhurba collages fragments of stories region by region. Titles mark the places where Zhurba put down her camera and measure the distance of the respective locality from the warfront. The young filmmaker’s vision oscillates between a profoundly humanist attention to individuals, and a recognition of the dehumanization imposed by the structures of war.

Zhurba’s mastery lies in her meticulous observation: every hand, gesture, piece of clothing, or fragment of a voice reveals larger issues. War bleeds into the everyday, tearing apart family members and breaking the fabric of normal life. The filmmaker’s feminine gaze remains measured, caring at times, yet never sentimental. One of the first scenes of the film could be taken from a Hollywood WWII film: images of overbearing crowds and families separated at a train station – luggage being passed through windows, arms stretched out in despair. The scene appears almost staged, as if fictional. Yet all that Zhurba films is the bitter truth. Elsewhere, masses of cars are stuck in long queues of traffic as Ukrainians seek to escape the war. Verbally fighting, anxious, and unable to move, we can see their disorientation.

The subject of war is not foreign to Ukrainian cinema. Think of Larissa Shepitko’s The Ascent (1977), a devastating tale of solidarity set during the Second World War, or Elem Klimov’s epic war tragedy Come and See (1985). Most of Songs of Slow Burning Earth is imbued with a grey tonal palette and barren landscapes that bring to mind earlier Ukrainian films, for example the visual depth of Ukrainian poetic cinema, particularly Yuri Ilienko’s banned masterpiece A Spring for the Thirsty (1965), which similarly evoked wartime devastation through bleak yet stunning imagery.

The film’s intensity is unbearable at times, yet it is also strangely poetic. Beauty here becomes both troubling and consoling. Arthur Danto once wrote in The Abuse of Beauty that one of beauty’s roles is to be a form of consolation in the aftermath of catastrophe, recalling the improvised memorials under the rubble of 9/11. Zhurba’s images raise similar questions: is the aestheticization of horror a collaboration with the perpetrator, or on the contrary, is beauty the very means by which a nation achieves collective consolation? One of the most striking sequences follows a truck along a highway, where Ukrainians bow silently at the roadside. Here rhythm is key as it is only at the end of the sequence that we realize the truck carries fallen soldiers. The eventual arrival of the truck at a church, where crowds silently kneel down in mourning to greet the deceased, slowly reveals that, given the tragedy, the last recourse of the inhabitants is prayer. Over time, thousands of empty graves begin to punctuate the film.

This observational clarity becomes most unsettling in the morgue, where doctors examine unidentified bodies, associating causes of death with the injuries and cataloguing remnants left on the unrecognizable bodies – a half heart-shaped necklace, a cross, a watch – crushing symbols of interrupted lives. Children recount friends burned alive, Russian troops pressuring them to take sides. At the film’s conclusion, the dismantling of the Soviet “Motherland” statue recalls the toppling of Stalin and Lenin monuments in the 1990s. Yet here the gesture lacks the utopian optimism of post-Soviet independence; it feels instead like a necessary erasure of symbols of Russian presence without any promise of political renewal.

In the last moments of the film, we witness a school workshop. The young students were asked: can one still be happy while others suffer? Can life continue normally amid catastrophe? Their hesitant answers remind us that Zhurba’s film is not only a document of the present war, but also an ominous anticipation of wars yet to come. The closing scenes pause on schoolchildren practicing military drills as if to be ready for more fighting. Amidst these collaged stories, there could be a hidden arch to the narrative of this documentary: from the strident sirens we hear in the first seconds, the film takes us on a journey where human masses seek exile. Following the commotion, the film goes on to report the sense of emptiness that is felt in Ukrainian forests, graveyards, and abandoned factories, to finally end in the absurdity of collective endeavors, which are epitomized by a seemingly innocent, choreographed march. I left Olha Zhurba’s masterful film with a silent cry and a feeling of despair. The film’s pain is never overly emotional and comes from a controlled and distanced beauty as well as thorough perceptiveness cloaked by a haunting soundscape.

Leave a Comment