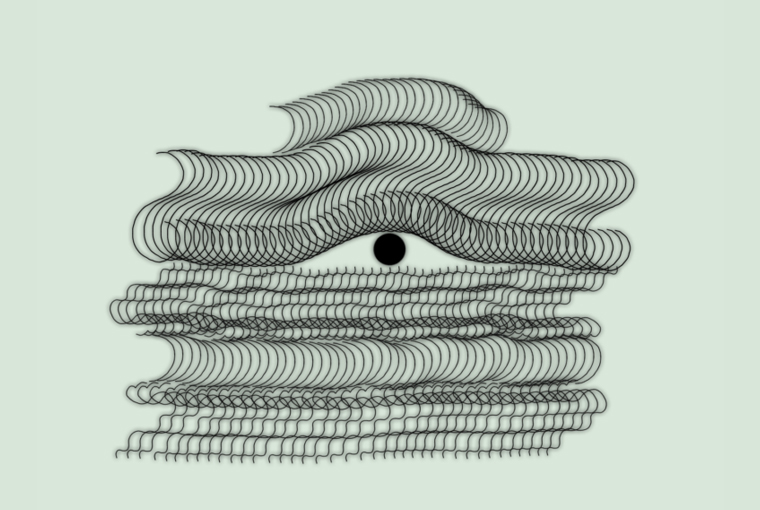

Soft lines appear and connect on screen before fading out, as if seen through a thin wall of haze. They look black at first but are actually a dark shade of green. Like everything about Intermission, the toned-down contrast conveys a softness and delicacy to the moving, shifting, and multiplying lines, dots, and patterns. A calming music with a strict rhythm and a carillon quality to it accompanies the dancing shapes.

Hungarian animation filmmaker Réka Bucsi is a kind of superstar in the animation world. With her films Symphony no. 42 (2015), which was shortlisted for the 2014 Oscars, LOVE (2017) and Solar Walk (2018), she won the hearts of audiences around the world. All of these films premiered at the Berlinale Shorts Competition and went on to be screened at a variety of renowned film festivals such as Sundance, Ottawa Animation Film Festival, BFI London Film Festival, and more. In 2018, her short film Solar Walk won the Audi Short Film Award at the Berlinale and was nominated for Best Short Film at the renowned Annie Awards. In 2021, she was invited to join the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and she has been a member of the European Film Academy since 2017. Her films have always had a dreamy, soothing, and gentle quality to them, displaying a charming and humorous oddity. They pay particular attention to rhythm and music, qualities that reach new heights in her newest animated short film Intermission.

While Bucsi’s previous films have mostly been crafted in an illustrative and figurative aesthetic, Bucsi explains that she started experimenting with abstract shapes during the beginning of the Covid lockdown in 2020. She was particularly inspired by the abstract animation work of German filmmaker Oskar Fischinger (1900–1967), who was a pioneer of abstract cinema. One of Fischinger’s main aspirations as an artist was to transfer music into visuals, an aim he already began pursuing in the very early days of sound films in the 1920s. He approached this by working with a style of abstract animation that was dominated by simple graphic shapes such as circles, triangles, and squares. While most of his work also heavily explores the impact of color, some of his early so-called Studies (of which there are 14), e.g. Studie Nr. 8, are kept in black and white. They explore reoccurring lines and rhythms, at times even favoring the auditory level over the visual one.

Réka Bucsi’s passion for a more abstract manner of filmmaking has already become manifest in the project Plante (2020), for which she collected biological illustrations of plants and critters from the Biodiversty Heritage Library, which she then rearranged in a rhythmical way to music by Johann Sebastian Bach.

Intermission builds on the tradition of intermission plates that have been used in film screenings to create a break for the audience. In Western cinema, they were used for comedies from the early 1960s, during screenings of films with excessive overlength, or whenever technical constraints necessitated them. Deriving from musical theater, the term “Broadway Bladder” was coined to describe “the alleged need of a Broadway audience to urinate every 75 minutes”.1 The break, following the example of recesses in the opera and theater, allowed the audience to follow mundane needs such as taking a toilet break or stock up on nibbles and drinks at the theater’s snack bar, an essential source of revenue for theaters. In addition, it enabled the audience to process what they had just seen and to mentally prepare for the remainder of the film.

The visual language of Réka Bucsi’s Intermission develops gradually. The film sets off with a blank screen on which lines begin to appear. The shapes become increasingly complex and the drawn motions multiply as the film progresses. In the beginning, the film’s format is as narrow as 5:4, but it gradually extends to one that is as wide as 16:9 as the film’s visual vocabulary diversifies.

After a while, the abstract lines and patterns take on a more figurative form. This is supported by the Pareidolia effect, which describes the human tendency of finding faces and figurative interpretations in objectively vague or randomly shaped compositions – whether it be clouds, everyday objects, or the cream in your coffee. From the purely abstract stimulation thus emerges what seem to be eyes, a group of giddily walking legs, and a swimming unicellular organism. Detecting these shapes triggers a remarkably pure and childlike joy. Watching the lines take on more concrete forms and come to life after minutes of entirely abstract stimulation is highly rewarding.

The word “animation” derives from the Latin word for soul, “anima”. This alludes to the phenomenon of animation breathing life into inanimate objects, into stop motion puppets, 3D character rigs or even drawn lines, as is the case in Intermission – animation endows these objects with movement, with a personality, and through this with a soul. In the very early days of animation, these short films were oftentimes performed and staged like a magic trick. An excellent example for this is Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur (1914), with which the director traveled around US-American theater stages for half a year, presenting it while interacting with the depicted dinosaur, even seemingly feeding it.

Consequently, the joy of seeing moving lines and patterns come to life as recognizable figures in Intermission, is an excellent example of the original illusion and wondrous quality of animation. Réka Bucsi’s Intermission succeeds in hypnotizing the audience. It allows them to marvel at the exceptionalism of simplicity and leaves them hungry for more.

References

- 1.Holland, Peter (1997). English Shakespeares: Shakespeare on the English Stage in the 1990s. Cambridge University Press, 3.

Leave a Comment