What Is Good, What Is Bad.

Yulia Lokshina’s Active Vocabulary (2025)

Vol. 162 (February 2026) by Margarita Kirilkina

Propaganda or political education? Denunciation or a necessary form of surveillance? The occupation of a foreign territory or its improvement? All these questions are posed nonverbally in the documentary Active Vocabulary (2025) by Yulia Lokshina, originally from Russia but living in Germany for more than twenty years.

The director reconstructs the story of a teacher from a Russian village in the hinterland who, during a school lesson, spoke out against the war in Ukraine and was recorded on a mobile phone by one of her students. As a result of this incident, Maria Kalinicheva was forced to emigrate to Berlin, as she faced pressure not only from the school administration but also from the district authorities.

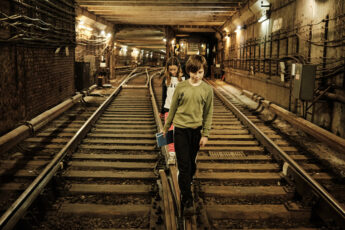

Together with Maria, children from a Berlin school recreate situations from the Russian school where she used to work. They embody pupils, teachers, and the administration, placing themselves in the skin of characters who cannot be filmed but can be represented all the same. Through these performances, the Berlin students relive the story themselves and enter into dialogue with the teacher: they ask her questions from the perspective of the German education system, where teachers are not allowed to transmit their political views but are instead expected to let students decide for themselves, to help them develop their critical thinking. But is this really possible? Can education ever be neutral? And history? Even geography – are they political, or not? The filmmaker does not answer these questions, but instead simply shows how the education system functions, leaving the spectators, like the students, to decide for themselves.

To visually connect the distant locations of the two schools, Yulia Lokshina incorporates a 3D animation of the Russian school (by Felix Klee), a school left behind in the past, to which Maria has no physical access just as she has no possibility of returning to her homeland. The visual reconstruction of the space helps situate this case within the environment of a disciplinary institution, where a voice recording moves from a student to a sports teacher, then to the highest authority – the school director – and finally to politicians. At the same time, politicians were sending another message about what teachers must transmit to children regarding the ongoing war in Ukraine. This forms a perfect circulation of information within a perfectly organized space. It is no coincidence that the student who made the recording voiced her wish to become an FSB agent. A perfect coincidence.

The parallel storyline concerns the preparations for building a new school on forest land near Moscow, which Yulia Lokshina had filmed at the beginning of 2022 for another project, shortly before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Here, the roles are reversed and appear prophetic with regard to what would happen a few months later. Uzbek workers hired by a construction company mark the boundaries of the future school in the middle of the forest. Local women try to stop them, accusing them of occupying the territory and telling them to return to work in their own country instead of taking over the territory of another state – ignoring the fact that the workers are merely carrying out someone else’s orders. A few months later, these same workers will be carrying out a different order in Ukraine, as executors of evil.

To figure out what is evil and what is good in this film, amid the constant switching of roles, becomes the task of the spectator themself. A few hints are given, but the film still presupposes active participation from the viewer, refusing to provide a clear narrative and instead proposing that they construct their own story while offering different variations of how it could go. This variability is conveyed, for example, in the scene where the Berlin students record the teacher’s speech on a phone: multiple possibilities are suggested as to how this might have happened – the phone could have been hidden in a sleeve, in a book, under a foot, in a pocket, and so on. The children also keep switching roles; there is not one but several headmistresses, each expressing different opinions. The story is not given but flexible, and the language in which the story is written is not fixed but becomes an active vocabulary. The spectator must either choose from what is offered to them, or imagine their own variation.

Leave a Comment