The Yugoslav Weird Wave

Matevž Jerman and Jurij Meden’s Alpe-Adria Underground! (Ali je bilo kaj avantgardnega, 2024)

Vol. 151 (January 2025) by Isabel Jacobs

Screened in the European Panorama Special section at the 2025 Crossing Europe Film Festival Linz, Matevž Jerman and Jurij Meden’s Alpe-Adria Underground! (2024) takes viewers on a wild 98-minute ride through the fringes of Slovenian experimental cinema. A time-lapse of experimental film history, the documentary assembles fragments from over sixty works created on the slither of land between the Alps and the Adriatic Sea. They were all made outside the state production system, in amateur film clubs and by independent artists.

Over the past decade, the Slovenian Cinematheque has collected and digitized more than 170 short films produced during the Socialist era. Jerman and Meden present a chocolate box of the weird and wonderful, offering a glimpse into the golden age of Yugoslav underground film. Their documentary has sparked efforts to digitize and restore a trove of cinematic gems that have remained largely unseen.

A vibrant underground film culture emerged parallel to official, state-sanctioned film production – what might be termed the Yugoslav Weird Wave, a movement that emerged in parallel to, and at times intersecting with, the Black Wave. Amateur film clubs, provided by the government with cameras and film stock, sprang up in nearly every village. Anyone interested in film was able to experiment as equipment passed around freely. Emerging filmmakers joined forces with Slovenia’s art scene, blurring the lines between film, performance, and conceptual art. Soon a network of experimental film festivals emerged.

There are few artists as legendary as OM produkcija (OM Production), a shadowy force behind dozens of wildly inventive 8 mm and 16 mm films created between the late 1970s and early 80s. The identity of OM has always been kept a mystery – was it the work of one obsessive auteur or a collective of 50 underground artists? Using bizarre pseudonyms like Veronique Gartenzwergel, Emannuel Gott-Art, and Ismailhači Cankar, their films are a kaleidoscope of Yugoslav youth culture, capturing the transition from hippie and psychedelia to punk.

OM’s work was rooted in an experimental investigation of authorship and gaze, challenging the myth of the director through their anonymity. Galactic Supermarket Presents Cosmic Rainbows (Galaktični supermarket predstavlja Kozmične mavrice, 1977) unleashes a psychedelic stream of scratch animation and rapid-fire imagery – cinema as a sensory assault. OM Production earned cult status with B Dislocated Third Eye Series III: Bismillah / In Four Movements (Serija Dislocirano tretje oko III: Bismillah / v štirih stavkih, 1984), part of the Dislocated Third Eye series, which was made without looking through the camera.

In Bismillah, we see OM Production spinning the camera like a hammer, exploring what Ivan Ramljak calls an exploration of “the kinetic possibilities of the camera.” The result is a dizzying vertigo and, eventually, the breakdown of vision. Intertitles flash up: “In every second of life, there are 24 pictures of death. / Meaning is created not by the filmmaker but by the film. / We go through time and space. / Our eyes are in excellent condition.” A cosmic cinema of erasure and death.

The boundary between performance and film collapses when the screening becomes part of the work. One film by OM Production had to be projected in the corner of a room, turning the screen into a three-dimensional object, another onto the filmmaker’s own face. Screenings at ŠKUC (Student Cultural Centre) and the Moderna Galerija placed OM within both avant-garde cinema and Ljubljana’s art scene. Kumbum (1975–1987), a two-hour barrage of nearly 12,000 shots culled from TV, claimed to make viewers “absolutely abstracted.” As OM Production put it, “for them, stories begin to happen within the film.”

Seriality and fractured repetition replace narrative, provoking a different sort of suspense – the compulsion to construct meaning from a series of disjointed patterns. Are works like Kumbum and Bismillah really “amateur” films? Alpe-Adria Underground! opens by asking how such films should be classified and whether it even matters. Drawing on Slovenian film theorist Silvan Furlan’s text “Was there an avant-garde?,”1 Jerman and Meden set out to explore a world different from anything produced within official paradigms of the time, whether it was made under the labels “experimental,” “avant-garde,” “parallel,” “alternative,” or even “anti-film.”

However, labels matter when it comes to the marginalization of film heritage. In Slovenia, experimental film was often dismissed with the help of the derogatory term “amateur film,” which was used to sideline any production made outside the official system. As Furlan already noted, this categorization meant that many of the works were never systematically preserved by cultural institutions. Yet, Alpe-Adria Underground! shows that so-called “amateurs” produced radical and original works that form the belatedly recognized corpus of Slovenian experimental film.

The documentary is structured around quotes by Furlan, paying homage to the Gorizia-born critic and founder of the Slovenian Cinematheque who pioneered the study of amateur film. The story begins with Boštjan Hladnik, the father of Slovenian avant-garde film, who became famous in the 1960s for importing the spirit of the French New Wave into Yugoslav cinema. Among his earliest works is the short film Fantastic Ballad (Fantastična balada, 1957), a haunting black-and-white animation based on drawings and prints of Slovenian surrealist painter France Mihelič.

What makes Hladnik’s work unique is a dreamlike fusion of fairytale and absurdist philosophy, with a voice declaring: “There is no reality.” Dušan Makavejev considered it to be Yugoslavia’s finest animated film. Jerman and Meden show how animation, a genre-crossing practice, turns the medium inside out. This experimental spirit is exemplified in the work of animation pioneer Črt Škodlar, a key figure in Slovenian puppetry, whose Morning, Lake and Evening at Annecy (Jutro, jezero i vecer v Annecyju, 1965) is an abstract homage to the Annecy Festival, using cut-out animation to visualize music.

Visual artist Tone Rački, who is also among the interviewees, contributed to Slovenian amateur animation with transgressive films such as Everybody Was Coming (Vsi so prihajali, 1971), which animates Picasso-inspired, erotic drawings of women masturbating, set to a folk song. As Rački himself put it: “a classy provocation.” In Love at First Sight (Ljubezen na prvi pogled, 1972), he continued to experiment with drawing geometric figures and forms.

The 1960s and 70s saw a democratization of cinema, driven by the rise of amateur film clubs. One of the most remarkable figures from this era is Vinko Rozman. Between 1963 and 1971, working within Kino Klub Ljubljana, Rozman produced over twenty shorts, ranging from sports film to formalistic study, some socio-political, others deeply personal. Echo and Response (Odmev in odziv, 1965) is a tender and poetic concept film, both atmospheric and cerebral in its exploration of sound. Ki Komp Pa (1971) shows Rozman aligned with the New Art Practice and Slovenia’s performance scene.

His most haunting and politically charged film, Prague Spring / After Jan Palach (Praga spomladi / Po Janu Palachu, 1969), blends documentary footage, voiceover, and personal photographs to reflect on repression and mediality. Shot during the Prague Spring and the subsequent invasion of the Warsaw Pact, the film reflects on the act of witnessing: “Where a man ends, a flame begins.” Of the many Yugoslav students in Czechoslovakia at the time, Rozman was one of the few who turned to his camera, creating a lyrical time-capsule.

The only woman filmmaker featured in the film is Ana Nuša Dragan, whose wildly funny self-portrait Because of and So (Zato in tako, 1968) shows her smoking, chewing, and posing for the camera in sunglasses with self-irony. Working with her partner Srečo Dragan, she moved between video, conceptual art, and film pedagogy. Her first documentary Some Information (Nekaj informacij, 1968), a farewell to student life, captures her moving out of a dorm with the help of artist friends. Her most memorable work is the 8 mm film Communication of Gastronomy (Komunikacija gastronomije, 1971), in which she films friends eating sausage until their gestures freeze mid-bite.

Communication Gastronomy feels as though it was a canonical part of 70s feminist experimental film, evoking Dragan’s more famous contemporary Sanja Iveković and, in particular, Natalia LL’s Consumer Art (Sztuka konsumpcyjna, 1972–1975). Yet Dragan laughed off the idea that she was the only woman in the scene where she was active, recalling in a 2009 interview, cited in the film: “Yes, but I wasn’t aware of that… I found that out now!”

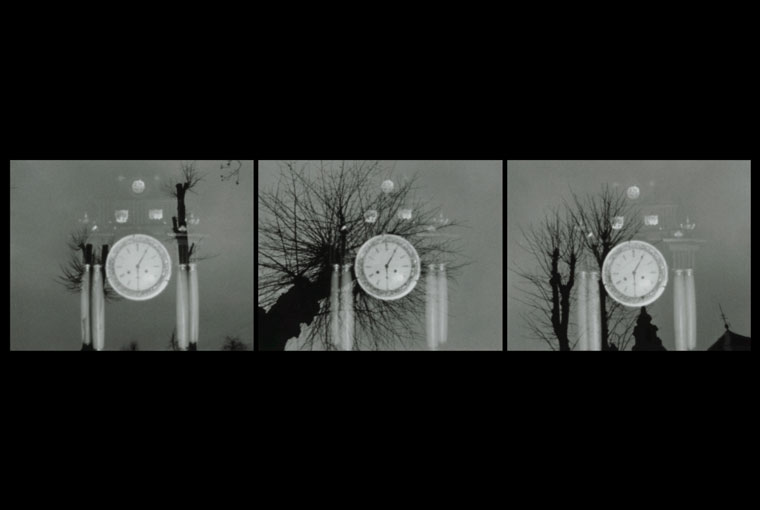

Among the most daring experimentalists from the 60s is Vasko Pregelj, whose films blend poetic beauty with apocalyptic imagery, and are reminiscent of early 20th-century expressionist film. In Requiem (Rekvijem, 1966), black-and-white images of plant forms morph into cosmic patterns before being consumed by flames. Photographs burn and fire becomes a metaphor for time itself, engulfing everything. Similar motifs recur across his works Fantasy (Fantazija, 1965), Dreams (Sanje, 1966), and the hauntingly beautiful Nocturne (Nokturno, 1965), where multiple exposure is used to create what one of the critics interviewed in the documentary described as a variety of “Neo-baroque.”

Nocturne overlays images of snow, fire, clockfaces, and trees, all set to a soundscape of choral cacophony. Pregelj also worked as a painter, creating massive hand-drawn sceneries – sheets of painted paper hanging from clotheslines – which are shown in behind-the-scenes footage. By the time he was 20, Pregelj had completed ten films that explore dematerialization and the unmaking of images.

Towards the second half of the documentary, one figure takes over the screen: the Slovenian-Macedonian filmmaker Karpo Godina. The part dedicated to him feels like a film within a film, and could have easily become a documentary of its own. Famously elusive and difficult to interview, Godina steals the show, recounting how his mother, an actress, took out a loan to buy him his first camera – a foundation myth of the Slovenian avant-garde.

An important figure in the Yugoslav Black Wave, Godina studied theater and radio in Ljubljana before beginning to make amateur films. He quickly moved into 35 mm, retaining the playful, anarchic spirit that defined his early works.2 His three shorts featured in the film – some of the most radical works of their time – tread the line between Slovenia’s experimental scene and the larger Black Wave movement. Collaborating with the likes of Želimir Žilnik and Lordan Zafranović, Godina brought a breathless energy to both fiction and nonfiction, always questioning the politics and poetics of cinema.

Godina’s films feel cult, wildly free, and technically audacious. Game (Divjad, 1965), based on a poem he found in a Croatian literary magazine, transposed poetry into film language. We watch a girl walking, staring into, across, and around the camera, her image cut from shifting angles. Her eyes’ pull is magnetic. When a young man appears, the camera’s perspective shifts between the two of them. The camera is less voyeur than itself the very object of observation – an anarchic game of gaze. Žilnik, who sat among the audience in Linz, called Game a drama about fate and desire, “the magnetism of union.” Subverting the male gaze, Game lets the man be seen and objectified by the woman, injecting erotic suspense and uncertainty: “Will they speak, hold hands, or get lost forever?”

Works like Anno Passato (1966) showcase Godina’s mastery of in-camera editing. Filmed on 8 mm with double exposure and working with rewind, it creates a monochrome choreography of light and movement. “We were technological freaks,” Godina recalls. Dog (Pes, 1966), meanwhile, is a delirious, alcohol-fueled short in which the camera follows a dog through chaos and hallucination, until suddenly catching open streets from a window – a breath of air before diving back into delirium. Full of humor, eroticism, and play, Godina’s films blend anarchic spirit with formalist experimentation.

The Gratinated Brains of Pupilija Ferkeverk (Gratinirani mozak Pupilije Ferkeverk, 1970), plotless and wordless, is a mad montage of naked youth – mostly Slovenian poets caked in mud and hippie girls with turquoise eyeshadow. They stare blankly at the static camera, drink Coca-Cola, hold flowers, and drop pills. Often read as a parody of “reism” – a literary movement treating humans as objects – the film is a funny, psychedelic post-68 spectacle.

About the Art of Love or a Film with 14441 Frames (O ljubavnim veštinama ili film sa 14441 kvadratom, 1972) is even stranger: shot during Godina’s military service in Macedonia, it documents the odd separation between a soldier camp and nearby factory girls. Like in Game, Godina plays with the suspense of desire. When the military saw it, Godina was called to court and told to destroy the film.

Healthy People for Fun (Zdravi ljudi za razonodu, 1971) became a cult film before being banned in 1972, with Godina being accused of dismantling Yugoslavia’s sacred principles of brotherhood and unity. It presents static tableaux of rural Vojvodina and its people and animals. Godina’s films moved between satire and seriousness, dark humor and anarchic joy – a true pioneer of the Yugoslav Weird Wave.

And he wasn’t the only one filming under the influence. Matjaž Žbontar’s trippy An Orange or Harmful Influence of Drugs on Youth (Pomaranča ali škodljiv vpliv drog na mladino, 1973/1975) revolves around a group of stoned friends who put an orange in the oven. The film follows the surreal logic of a trip: the orange later reappears as the sun and eventually, masterfully montaged, it blows up a building. Žbontar’s delirious celebration of his druggy friends radiates total freedom. Cinema as a higher state of consciousness.

An Orange stars Drago Dellabermadina, a member of the influential OHO Group, an avant-garde collective from the 1960s that bridged performance, conceptual art, and experimental film. Another member of OHO, Naško Križnar, created multimedia happenings like White People (Beli ljudje, 1970), an absurdist Gesamtkunstwerk. The film shows a bunch of people moving as a flock, a mouse crawling over a naked body, and bodies wrapped in foil or covered in foam. As Križnar recalls, it was all driven by OHO’s “lust for life”: white People, the premise of the film goes, dress in white, live in white houses, have white pets, drink milk, and celebrate festivals when it snows.

Yugoslav hippie cinema is represented by Franci Slak, experimental poet and weird schoolboy from Koper. Slak’s Danse Macabre (1971), an eerie environmental parable featuring gas masks, is an unsettling portrait of 70s sensibility: the film radiates a sense of nuclear threat, pollution, and the desire for new collectivity and a return to nature. As quoted from Slak in the film: “Amateur film was expressed more through symbolism than through narration. It was a simple symbolism: a lone traveler through the Atomic Age.”

Daily News (Dnevne novice, 1979), Slovenia’s first feature-length experimental film, stands out. A poetic film diary, Daily News portrays workers, children, and friends, street scenes, construction sites, and monuments. Slak recorded his everyday life for one year. As Furlan put it, the film “nostalgically evokes the golden times of the underground.” Daily News is silent and supposed to be screened with a random radio news broadcast of the day.

Marking the transition from hippie to punk, Davorin Marc pushed the materiality of film to its limits. A punk filmmaker from the Slovenian coast, Marc was largely self-taught and highly experimental, producing hundreds of films that reinvent – and pioneer – avant-garde techniques. Many of his films exist as unique prints, contrary to the logic of cinema as a medium of reproducibility. One of his films even destroys itself when screened, only allowing a single viewing.

Like OM Production, Marc embraced decay, erasure, and death. He scratched directly onto film stock, made a film with no hands, and chewed celluloid. In Bite Me. Once Already (Grizi me. Jednom već, 1979/1980), teeth marks create a trippy visual imprint, breaking the boundary between body and film strip. His Fear in the City (Paura in Città, 1984), is a frenetic Super 8 film with a video look, channeling the raw energy of Yugoslavia’s coastal punk scene. As the documentary shows, Marc is still making films today – a testimony to the fact that Slovenian experimental film is far from over.

The avant-garde is very much alive and evolving, mostly spurred today by young women artists. Alpe-Adria Underground! closes with a fast-paced clip featuring recent works in digital forms that expand the boundaries of film, including Katarina Jazbec’s You Can’t Automate Me (Automatizacije ni mogoče izvesti, 2021), Kristina Kokalj’s Memory Machine (Stroj spomina, 2018), and Ester Ivakič’s Magical Castle Is Here Now (Čarobni grad je zdaj tukaj, 2021). In this final chaotic stream of images — the culmination of an at times overwhelming montage of clips — Sara Bezovšek’s www.s-n-d.si (2021) stands out for radically reinventing the medium.

In Bezovšek’s screen-recorded hellish descent through an interactive story-game, doomscrolling becomes cinema. Layered with GIFs, hyperlinks, memes, music videos, YouTube clips, and surreal clickbait (“Why Does My Dog’s Cuteness Make Me Want to Hurt Him?”), the film spirals from a pixelated heaven down through environmental collapse, zombie apocalypse, and biblical disaster into the cosmos, culminating in a menu of possible endings, bearing titles such as “Human Extinction,” “Utopia,” and “Dystopia (Coming Soon).”

Alpe-Adria Underground! draws freely from the irreverent, wild spirit of the Yugoslav Weird Wave. In many ways, it is the foundational document of such an avant-garde — its filmic manifesto. The texture is playful, experimental, and eclectic, using split screens, erratic montage, talking hands, voiceover, and music. Watching Alpe-Adria Underground! can feel both disorienting and exhilarating; its visual overload raises questions about how we can access, watch, and participate in forgotten film heritage.

Ultimately, Jerman and Meden’s aim is not to answer their initial question – how to label and organize film history – but to spark curiosity. Rather than offering a critical analysis, their documentary is a love letter to the obscure figures of Slovenia’s underground cinema. With minimal biographical context and only fleeting glimpses of each work, it’s less a historical survey than an invitation to imagine the vast, unseen archive beyond the screen. Hopefully, the Slovenian Cinematheque will soon make these films more widely available — allowing the “weird wave” to secure its place in the textbooks of global film history.

- Furlan, S. (2010). Ali je bilo kaj ‘avantgardnega’? Ljubljana: Zavod za odprto družbo – Open Society Institute. ↩︎

- Kirn, G. (2013, December). The early works of Karpo Godina. Retrospectives, East European Film Bulletin. Retrieved from https://eefb.org/retrospectives/the-early-works-of-karpo-godina/ ↩︎

Leave a Comment