We met archivist, curator, and filmmaker Jurij Meden at the Crossing Europe Film Festival in Linz (29 April–4 May), where his and his co-director Matevž Jerman’s “Alpe-Adria Underground!” screened as a special. The film chronicles Slovenia’s rich if overlooked history of underground cinema. In our conversation with Meden, we discuss the origin of the film as well as its complicated historical background.

How did you come to make Alpe-Adria Underground! together with co-director Matevž Jerman? Where did the idea come from, and how did you end up working with this material?

It actually started a long time ago. I’m originally from Ljubljana, Slovenia, and as a young cinephile, I would often travel to Vienna, to the Austrian Film Museum, to watch avant-garde films. At the time, there was no tradition of exhibiting “experimental” or “avant-garde” films in Slovenia. I’m using those terms interchangeably – I know that may not be the most correct thing to do, but still.

As I watched more and more experimental films and learned about their history, I noticed something odd. Experimental cinema is supposed to be the most open, all-embracing, inclusive branch of filmmaking – but in reality, it seemed to be the most Western-focused of all existing film histories. When you read film historical books on experimental or avant-garde cinema, it’s mostly New York, Paris, Vienna, London, Los Angeles – as if only the Western world nurtured those traditions of avant-garde cinema.

I grew up believing that there was nothing special happening in this field in my own country – not just Slovenia, but also Yugoslavia, where I was born. And then, about 25 years ago, I accidentally stumbled upon a filmmaker: the guardian of OM Production. Someone told me that there was this person living in a Slovenian coastal town who had made dozens of films. They said it might just be one person, or maybe 50 people.

So I actually drove down there and saw 50 fantastic films, all shot on 8 mm, in their house. Whether it was him, her, or them – we shouldn’t really define the identity of OM Production, they still wish to remain anonymous. And I was blown away. Because in former Yugoslavia, there was the official, state-sanctioned film production, but there was also this incredibly rich parallel culture of film clubs that the government would establish in practically every village.

They provided the film clubs with 8 mm film stock, projectors, editing equipment – everything. And everybody could come and make films: workers, students, anyone who was interested. Now, what happens when you give a bunch of kids an unlimited amount of 8 mm film and tell them they can do anything they want? Obviously, a lot of ephemeral stuff gets made – but also plenty of great, adventurous things, completely unburdened from any rules or regulations.

So I started researching, and the more I dug, the more I found. I was literally going to filmmakers’ bedrooms. Films I discovered weren’t being preserved by any archive, and no one had ever written about them. It was a complete blind spot in local film history.

About fifteen years ago, I was working at the Slovenian Cinematheque, which, at the time, had a very open-minded director, Ivan Nedoh. He was very supportive of the idea of establishing a special collection for these avant-garde films.

So we started collecting and restoring them. At first, we restored them very slowly, because the Slovenian Cinematheque didn’t have any restoration equipment, so we had to work with other labs. About ten years ago, the first batch of films was restored. These included three films by Karpo Godina – arguably the most famous of the bunch – a film by Davorin Marc, a punk filmmaker from the coast, and one short film by Vinko Rozman.

We showed these films at a couple of film festivals – we were invited to Oberhausen and some film museums – and the reaction was overwhelmingly positive. People were like, “Oh great, this is what was being made behind the Iron Curtain!” I mean, Yugoslavia wasn’t really behind the Iron Curtain in the way people imagine, but the idea that experimental cinema could also exist on the margins was pretty new.

Then, about five years ago, Ivan Nedoh, who now heads the archival department at the Slovenian Cinematheque, called me. At the time, I was already living in Vienna. He asked me to come back to Ljubljana and make a documentary film about this film history. He was able to secure a small grant, something symbolic, around €20,000. And I immediately said yes but that I couldn’t do it alone because I wasn’t living in Ljubljana anymore.

So we invited Matevž Jerman, my very good friend, to co-direct the film. He also worked with Ivan at the Slovenian Cinematheque, scanning all these films that you see in our film. And that’s really when the film was born.

Speaking of the deconstruction of the whole idea of an “Iron Curtain,” that there was an avant-garde in New York, Paris – and nothing else. Now we’re seeing Soviet Parallel Films emerging, underground films from the GDR… Your film focuses on the Slovenian or Ljubljana scene, but what were the networks across Yugoslavia among film scenes at the time? And maybe also beyond – to other Eastern Bloc countries? Were people watching American films?

That’s a very good question. In Yugoslavia, as I mentioned, there was this parallel structure of film clubs. But there was also a parallel structure of film festivals. In the 1950s and 60s, these were called “amateur film festivals.” Everything that was produced by those film clubs was dismissed as “amateur” work and not taken seriously by archives, historians, or film critics.

But in the 1970s and 80s, these amateur film festivals evolved into proper experimental film festivals. So domestically, filmmakers were aware of each other. They were sharing work, watching each other’s films. But a lot of them weren’t really familiar with what was happening internationally, outside of Yugoslavia.

Take, for example, films by Davorin Marc. He is a very interesting director. He made over 200 films, maybe even 500. And he basically reinvented a lot of techniques that had already been developed elsewhere – without being aware that it had already been done before.

For example, he had this crazy idea of making a film without a camera, by scratching directly on the film stock. And he did that without really knowing of Norman McLaren or Len Lye. And then he had an even more radical idea which I don’t think anyone else ever did anywhere – he made a film even without using his hands, where he was chewing a piece of celluloid, creating this abstract film with his teeth and saliva.

Still, there wasn’t much communication between Yugoslavia and other Eastern European countries. Maybe also because Yugoslavia really wasn’t part of the “Eastern Bloc,” we had a benevolent dictator and a pretty much open regime. Have you seen the Romanian film showing here, The New Year Never Came [(Anul Nou care n-a fost, 2024)]? It shows poor Romanians trying to swim across the Danube in the middle of winter to escape to Yugoslavia because it had open borders.

But we were really not familiar with other Eastern experimental scenes. It was only much later that I discovered the glorious tradition of the Béla Balázs Studio. And now I’m just beginning to learn about Polish or Czech experimental and animated film culture. These films are out there – you can find them and read about them – but I think there should be an orchestrated effort to bring them into the global canon. Because the work is extraordinary.

Another question about the term “avant-garde,” even though you said at the beginning we could also call the films “experimental” or “amateur.” The question of whether there was an avant-garde in Slovenia also opens your film. And if we look at the underground Ljubljana art scene in the 80s, there’s a lot of theorizing around the question of art history and the role of the avant-garde. Think of notions like “retro-avant-garde” or “second avant-garde,” as avant-gardes that are not just ahead of their time but also play with the idea of ironically recycling the past. Is this something more important to the New Art Practice and collectives like NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst), or do you also see a reflection of this in the films you discovered?

A lot of film historians insist on calling the films we portrayed “amateur films,” saying we shouldn’t call them “experimental” because the filmmakers themselves didn’t call them like that when they were making them. And to that, I say – yes, we are using the label retroactively just to make a point.

If I had to classify these films today, I would call them experimental, because it’s simply easier to show them as experimental films and to understand them that way. But then within Yugoslavia, you had different schools of thought. In Zagreb, for example, they were, let’s say, the most serious ones when it came to combining filmmaking with theory. They invented this notion of “anti-film.” In Belgrade, they had a slightly different idea: “alternative film.” There were all kinds of debates – often quite redundant, in my opinion – about how to define “experimental” in contrast to “avant-garde” film.

Now, with the Ljubljana theoretical school, the situation was different again. You mentioned the 80s – yes, there was a lot of theoretical activity then, around the “retro-avant-garde.” This is something completely disconnected from the film scene we focused on in the documentary.

Do you think the stuff from the 80s is maybe also more well-known or available online? I am thinking of Marina Gržinić’s video work, for example.1 With your material, I was exposed to most of it for the first time.

There’s still a huge issue with restoring and making video art from that period visible. I think video art from the 70s or 80s is in a much more difficult situation. With the material that you see in our film, 8 mm, 16 mm reversal film, sure, it’s scratched, sometimes heavily, and frames are missing, but still it’s relatively well-preserved. When you scan it and do even a minimal restoration, you can really make it shine. But how do you restore a piece of video art that was maybe shot using the first generation of Betacam, then migrated through three other analog video formats?

There’s this new practice, where there are organizations specializing in restoring video art and they remaster, upscale, and upgrade it – but that produces a visual object that never really existed.

How much material did you discard in the end? How did you decide what should end up in the film? And how did you decide which filmmakers to include – mostly men, it should be noted, and only one woman?

I’ll be honest, our film is just the tip of the iceberg. Take someone like Vinko Rozman, he made dozens and dozens of films and we show maybe seven. Most of these filmmakers, and yes, unfortunately most were men – only one woman – were very prolific. We were only able to present a tiny fragment from their bodies of work.

In some cases, Matevž and I were able to decide what we want to show – but then there were filmmakers who were quite particular. They were quite precise about how they wanted to be presented. And we were actually very grateful for those constraints – they forced us to be creative.

For example, OM Production made around 50 films, including one feature. But we were only allowed to show three shorts and some fragments from the feature. Davorin Marc, another brilliant filmmaker, made over 200 films. He gave us permission to use only five or six. He would not object to the public screening of his films, but he wanted only certain material to be included in the film. Again, really the tip of the iceberg.

I must add that we almost completely avoided going into biographical details. Partially because we really wanted the talking heads to tell the story, without any voice-over narration. More or less, the only person who really generously shared his personal background was Karpo Godina. The others were either no longer alive or declined being interviewed. Godina was able to share a lot, so we ended up learning about the personal and political context mostly through him.

It’s interesting that the idea of anonymity seemed to be an important gesture to many of these filmmakers. Some wanted to disappear behind the camera or abandon directorship altogether, as in the case of OM Production – where experimental film blends into performance.

Yes, absolutely. OM production is not only a filmmaking entity; it exists on the border between cinema and contemporary art. It’s a very loose border today, it barely exists anymore, but at the time, it was radical. He or she or they are also a very important figure in the history of Slovenian contemporary art, just like OHO, for instance.

One of the filmmakers we feature, Naško Križnar, was a member of OHO, a very famous avant-garde group of the 60s recognized as important for contemporary art but never really appreciated for their filmmaking before.

At the end of this year, OM Production will have a big exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Ljubljana. For him or her or them – again, I don’t want to identify them – it was all about performance from the start. In fact, most of their films are not just films, they’re supposed to be performances. Actually, there are very few that you just screen. The others are either shown as double, triple, or quadruple projections. Others are meant to be screened onto the body of the filmmaker. There’s a fragment in our film where you can actually see the face…

She, he, they were always exploring certain fundamental notions of filmmaking, of the gaze. OM Production has this series of films called Dislocated Third Eye, which was all about making films without looking through the camera. And there are fragments in our film from a film where the camera is swung on a tripod, and it looks fantastic! You could technically identify the filmmaker from that footage if you wanted. The idea of performance was inscribed from the start in the idea of filmmaking – or vice versa, maybe it was performance that used the medium of cinema.

It’s curious where underground films end up, if they are preserved at all. Take Soviet Parallel Cinema, which is quite precarious in terms of archiving.2 It can be hard to gain access to those films. A few years ago, I met a member of the Necrorealists, called “Debil,” and he just opened a suitcase and said, “Here are my films.”

Necrorealism is very parallel, really on the fringes. Actually, you might be interested to hear that at the Austrian Film Museum we’re currently working with the brilliant artist Masha Godovannaya who also happens to be the widow of Evgeny Yufit. She brought a lot of films to us, also from their old flat in St. Petersburg. Eventually we want to properly restore his works. It’s a huge undertaking, but yes, exactly the kind of “parallel cinema” we’re talking about. And it is comparable with the Yugoslav avant-garde: people working on the fringes and doing their own thing.

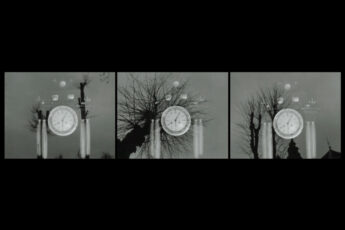

You had this split screen effect in your film; sometimes we see a talking head and then two or three other image streams. Was that aesthetic decision also a way to gesture toward the kind of fragmented, multilayered practice you encountered?

Yes, absolutely. We were thinking a lot about how to approach editing. What we really wanted to emphasize was the diversity of the scene. Not just, “Here are one or two interesting filmmakers,” but rather that there was a whole tradition, a huge movement, so we really wanted to cram in as much as possible.

At some point, we realized that even if we limited ourselves – like only showing one film per filmmaker – and edited traditionally (shot by shot by shot), the film would end up being six hours long. And we didn’t want that. I personally like shorter films. Even now, I think ours is a bit too long.

So we said, let’s go for the split screen technique and cram in as much as possible. But when we started doing that, putting one image next to the other, we realized that this is also something that allows us – in a very gentle, unobtrusive way – to analyze the films. If you listen carefully to what the people talking about the films are saying, they mostly share anecdotes or express enthusiasm. Often, they barely remember the films they saw in the past.

There is not much actual film analysis. And in fact, one objection I keep hearing, especially from more theoretically inclined critics, is that there’s not enough theory. And I get that. There’s no theory in the film, there’s very little critical analysis. But what we tried to do with our editing, with the découpage, was to create a visual analysis. Whether or not we succeeded is not for us to say, but that was definitely the intent: to show how these films actually operated. Some of the films were actually quite long, two of them feature-length.

I thought that was one of the strengths of the film. It didn’t need heavy-handed theory, it let the images speak for themselves. Some of the filmmakers you show are still around, right? I think you interviewed Naško Križnar in 2023. How do they reflect on that time? Are they nostalgic? Do they see themselves as part of a counter-movement to the Black Wave and more official Socialist culture?

These are really complex questions. The interesting thing is that of course, they all look back fondly on their youth, but they have different memories. We never made fun of them but I do think that it’s slightly funny how much they disagree when they talk about the past in the opening of the film: one person says, “We were censored under the old regime, it was hard.” And then another says, “That’s nonsense, we were never censored, we were absolutely free to do whatever we want!” They all have different theories.

Some of them knew each other back then, but not many actually worked together. More often than not, they worked with other artists. And yes, there was a clear connection to the movement that later became known as the Black Wave. In Yugoslavia, many filmmakers started their careers within the framework of film clubs. Slovenia is not the best example for this tendency, but if you look at Serbia, for example, many important Serbian filmmakers – like Živojin Pavlović or Slobodan Šijan – began their careers by making amateur films in film clubs.

In the Slovenian context, the only notable example would be Karpo Godina, who started making amateur films before transitioning to the 35 mm format and larger budgets, but retained his wild, anarchic spirit throughout. And then he moved into casual, mainstream narrative filmmaking. But there was a clear connection there. For example, the three 35 mm shorts by Karpo Godina that we present in our film as part of the Slovenian experimental tradition also overlap with the Black Wave. These films are now recognized as classics of New Yugoslav Cinema – a term preferred by most filmmakers themselves. A lot of the really big figures of the Black Wave, like Pavlović or Želimir Žilnik – we shouldn’t forget him – started as amateur filmmakers.

Your film captures not just film history but also youth culture in Yugoslavia, from the hippie movement and psychedelia in the 1970s to punk.

That’s a brilliant observation, no one has ever actually said that! But yes, you’re right. They were all young, and young people tend to form their own groups. In Yugoslavia, they organized in this way, moving from one period to the next one. In making the films that he made, Karpo Godina was a typical representative of the hippie generation. Notably, he openly advocated for the use of LSD in his wonderful film The Gratinated Brains of Pupilija Ferkeverk.

Then you had the punk movement, which Davorin Marc represents, and he’s often referred to as a “punk filmmaker.” Then you have OM Production as an echo of the hippie era. Obviously the whole OHO group was very much part of the 60s as well. But yes, it was young people hanging out. Very few of them were lone wolves. Davorin Marc and Vinko Rozman to a certain extent, but even they would make films with their friends.

There’s also a political dimension to this that is very interesting. Every film is a document of its time, and no film can avoid reflecting the ideology of its time. But the way ideology imprints itself into these films is different from the way this happened in official films. I will quote Želimir Žilnik, he once said something very beautiful. He said, “We have a habit today when we talk about cinema made in Yugoslavia or Eastern Europe at the time – you know, hard times, censorship – but when you take a look at these films, they’re so free, so open, as if there was no state interference.”

Now, obviously, these films were shown in very limited contexts, but then again, when have experimental films ever made it into the mainstream? They tell us a lot about Yugoslavia at the time. You know, most people have this idea that everything in the East must have been gray, drab, boring, depressing. But when you see these films, like those by Karpo Godina, people are constantly drunk or high, they are shown to be fooling around. It’s clear that all these films were made under some sort of influence. Nobody was sober while making them. The question is just what drug they were using.

There’s this beautiful film by Matjaž Žbontar, Pomaranča [An Orange or Harmful Influence of Drugs on Youth (Pomaranča ali škodljiv vpliv drog na mladino, 1973/1975)], which is all about getting super high. The premise of the film is completely absurd – they get high, they take an orange and put it in the oven. It’s a film about an orange made by a bunch of guys who are high.

You also show how alive experimental film is in Slovenia today. Often, you can get the impression that as soon as the “Iron Curtain” fell, that particular spirit of the underground was gone. Whereas you show a direct continuity with contemporary film.

That’s a fantastic observation, and you’re absolutely right. When the wall came down, it was like we lost interest in this cinema from the East. What I think happened was this: during the Cold War period, a filmmaker would occasionally defect from the East, like Polanski, Forman, Tarkovsky, or Makavejev from Yugoslavia. These filmmakers were greeted with open hands by the West. They would be hailed as champions and masters and they would bask in this newfound attention and glory. And they would confirm Western prejudices by saying, “Yes, it was super hard, we were persecuted, we couldn’t make films – it was so harsh. But here we are now, in the West. Finally.”

And the West was very happy with that. But no one really asked, “But wait – Andrey, how come you’re complaining? Didn’t you make five mega-spectacles in the Soviet Union? Didn’t you shoot a film, Stalker, twice because the first one had a camera effect? You had huge budgets for those films – multi-million-dollar budgets, in today’s money. So what are we talking about?”

I’m not saying that there was no censorship, but we really, really tend to exaggerate when we talk about censorship in the East, because the censorship of capitalism is much more insidious and effective than anything Eastern censorship could ever dream of.

Thank you for the interview.

- Jacobs, I. (2023, Summer). Red as blood: Marina Gržinić and Aina Šmid’s early videos. East European Film Bulletin, 136. https://eefb.org/retrospectives/marina-grzinic-and-aina-smids-early-videos/ ↩︎

- “Soviet Parallel Cinema,” East European Film Bulletin Vol. 109 (November 2020). https://eefb.org/volumes/vol-109-november-2020/soviet-parallel-cinema/ (Accessed 25 May 2025) ↩︎

Leave a Comment