The Forgotten Ancestors of Armenian Cinema

Tamara Stepanyan’s My Armenian Phantoms (Mes fantômes arméniens, 2025)

Vol. 155 (May 2025) by Anna Doyle

As I entered the center of Yerevan, making my way up to the main cinema hall of the Golden Apricot Film Festival in the Yerevan House of Cinema, built in 1974, I instantly understood how central Armenian cinema was to the Soviet era of film. During my stroll, I came across a poster of the 1920s film clown Leonid Yengibarov and saw a drawing of Sergei Paradjanov’s face adorning the street wall next to Yerevan’s Vernissage market, a large open-air flea market. I stumbled upon a copy of poetry by Sayat-Nova, the 18th century poet who inspired Paradjanov’s masterpiece The Color of Pomegranates. Behind it, an old man was selling vintage cameras and Soviet-era light-meters with a label reading “Leningrad.” Then, I finally arrived to see the first film of my personal program that day: My Armenian Phantoms by Tamara Stepanyan.

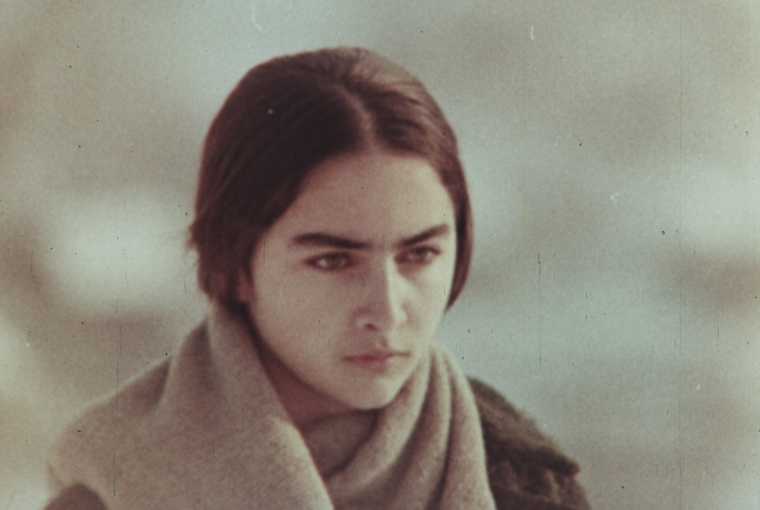

An Armenian filmmaker based in France, Stepanyan has become a strong voice in contemporary Armenian cinema. Her last film In the Land of Arto about the recent war between Armenia and Azerbaijan premiered at the Locarno Film Festival. Shot in parallel to Land of Arto, My Armenian Phantoms is a nostalgic voyage to meet the ghosts of Armenian cinema in dialogue with Stepanyan’s own story. To pay tribute to the metaphor Stepanyan uses, the voice-over takes us by the hand to dance in a circle onto the screen. To pastiche Paradjanov’s film title, it is the shadows of the forgotten ancestors of cinema that are at the center of My Armenian Phantoms. The film is an opportunity not only to discover hidden gems of Armenian cinema, but likewise to be touched by the simplicity of its poetry, revealed through archival black-and-white 35mm or Technicolor footage collaged together with Stepanyan’s own recordings. We see passages of early black-and-white silent films, historical dramas, melodramas, Communist propaganda, and Armenian New Wave films covering the period from the 1920s up to the collapse of the Soviet Union. By understanding its censorship secrets, ideologies, evolution, and traces, the film, as per Walter Benjamin’s expression, “brushes history against the grain,”1 adopting a vision of history told from the perspective of the oppressed that challenges faith in progress. The film does not follow a strict chronological order and avoids linear continuity, inventing its own narrative along the way as well as inserting excerpts from the personal family archive.

Tamara’s childhood home is Armenia, but also the world of cinema – her father, Vigen Stepanyan, was a famous actor during Soviet times. We, the spectators, might be touched when the voice-over becomes an apostrophe to her recently passed-away father, as the film is addressed to him. One of her earliest memories of cinema, showcased at the start of the film through family archives, is the familial ceremony of watching Armenian classics on Thursday nights. The voice-over is sometimes historical, at others sentimental; overall, it is rather simplistic and therefore fairly straightforward.

Female figures were just as important to Stepanyan’s artistic education as the self-important men surrounding her. There was her mother, who was a cellist, and her grandmother, who worked hidden away from the spotlight in film laboratories, in contrast to the many men behind the camera and those occupying leading acting roles. We see images of dinner gatherings with the whole family convening to the sound of traditional tunes. The family members had different attitudes towards the USSR: while her mother secretly took Tamara to church, many of the family members featured in the film believed in Marxist-Leninism and saw their world falling apart when Stalin died.

The philosopher Svetlana Boym, in her book The Future of Nostalgia, distinguishes between a “reflective nostalgia” – which dwells in loss and melancholy – and a “restorative nostalgia,” which reconstructs.2 Nostalgia is not necessarily negative; this reconstruction is often a way of finding one’s home, which resonates with how Armenians and the diaspora might feel. Stepanyan’s work is similarly reconstructive; it is also, to quote her, “therapeutic,” a tracing back of her origins, of approaching her father anew, and finally a way of understanding her Armenian roots. Tamara’s personal story, her growing up in a family of cinema and leaving Armenia behind at the age of ten for Beirut, brings the personal and the historical together in an attempt to better understand her lost home, which in this case is couched in Armenian visual language.

In the film, we look back at the history of Armenian cinema and are soon confronted with the fact that it has always been overshadowed by Soviet ideology and forced Russification. Films were often piloted by and under the control of the Soviet Russian film committee also known as ‘Goskino.’ Historically speaking, the Soviet Armenian government decreed the nationalization of cinemas in 1922 and The Armenian State Film Committee was not officially created until 1923. Armenfilm studios in Yerevan were created in March 1924. Throughout the 20th century, the studios produced a long list of films which underwent a constantly evolving discourse on nationalities – early on, Soviet Armenian cinema was framed within the internationalist discourse of art aspiring to be nationalist in form, and socialist in content. It is important to note, however, that even at times when the national identity of non-Russian Soviet Republics was allowed to be articulated, their autonomy was fundamentally repressed. One of the tropes of the early films suggested that the USSR had saved Armenians from the Turks after the 1915 genocide. Among the filmmakers remembered who produced films with Armenfilm were Hamo Beknazarian (known for Namus, the first Armenian silent black-and-white film, 1925), Henrik Malyan, Frunze Dovlatyan, Michael Vartanov, Levon Mkrtchyan, Atom Egoyan, J. Michael Hagopian, Sergei Paradjanov, Artavazd Pelechian, and many others.

That said, as this long list indicates, Armenian filmmakers from the Soviet period who are today remembered were all men. Yet, when watching passages from the films summoned in My Armenian Phantoms, one is touched by the representation of women even in early films from Armenia’s cinematic history. Hamo Beknazarian’s female characters are victims of a traditionalist and paternalistic society. Soviet propaganda claimed that Communism would overthrow the traditional patriarchy settled in Armenia. Stepanyan has called Beknazarian a ‘feminist’ filmmaker as he depicts the oppression of women3 – in one of his films, a woman is beaten by her father and then murdered by her jealous husband. “I am innocent,” cries the female character on the black-and-white intertitle.

It was not until the Armenian New Wave that gender representation shifted considerably. Frunze Dovlatyan was a radical voice emerging from the 1960s New Wave at a time when Armenia was shaking off Russification. His film Hello, It’s Me (Barev, yes em, 1965), the first Armenian film selected at Cannes, awakens feelings of freedom. Women are no longer victims of the patriarchy but masters of their own desires. Frenzied panning, New Wave existentialism, dancing scenes, and sexual liberation characterize this successful drama. The representation of the genocide would also change fundamentally by the late eighties. Closer to the fall of the Iron Curtain, through Yearning (Karot, 1989), Dovlatyan finally exposed the horror of the Armenian Genocide that had hitherto been tabooed outside of propagandist discourse. Also translated as “Nostalgia,” the film is wrapped in a nostalgic feeling for an Armenian home. It depicts the life of Arakel, an elderly man exiled during the Armenian Genocide, who in 1937 crosses into Turkey to reclaim his ancestral birthplace – only to meet a tragic end.

A more traditional take on poetic cinema accepted by the Communist regime were the films of Henrik Malyan, who studied at Moscow’s VGIK film school, with his notable masterpiece Triangle (Yerankyuni, 1967) capturing the beauty and simplicity of everyday life in a forge and the communal solidarity between blacksmiths. When a group of blacksmiths decides to go to war, the film inserts an insidious rebellious message. The blacksmiths sing a rebellious anti-Turkish song called ‘Zartir lao’ that was banned during the Soviet Union because it celebrated Armenian independence and rebellion. Despite the throes of propaganda, some of the films from the canon of Armenian cinema have hidden messages that are often communicated through song. The rural subject is also common in Armenian cinema. In his feature We and Our Mountains (Menk’ enk’, mer sarerë, 1969) Malyan films seasonal harvests and shepherds in the mountains of Armenia. Rural Armenia is also depicted, albeit more experimentally, in Artavazd Pelechian’s Seasons of the Year (Tarva yeghanaknery, 1975).

My Armenian Phantoms pauses to honor the cinema of Sergei Paradjanov, who is interviewed in archival footage about his life, not least about living under three different despots, with Paradjanov characterizing the history of Soviet films as a “cardiogram of terror.” Each filmmaker expressing their freedom is marked by the fear of starvation and torture. Images of Paradjanov’s funeral on 10 July 1990 show him laying calmly in an ornamented coffin at Kino Moscow in Yerevan, surrounded by flowers and a large crowd of people. Tamara Stepanyan was there as a child and remembers the ceremony, reminding us that he died just before the collapse of the Soviet Union, whose repression had caused him so much suffering.

I once attended a screening of a Paradjanov movie presented by his friend Serge Avedikian in Paris, and Avedikian told the audience that near the end of his life, Paradjanov said to him from his hospital bed: “Armenians know how to bury.” If burial is omnipresent in Armenian cinema and in Paradjanov’s work, in the Color of Pomegranates (Sayat-Nova, 1969) or Shadows of Forgotten Ancestor (Tini zabutykh predkiv, 1965), it is always an opening toward a new and more spiritual afterlife, or even a form of resurrection enabled by artistic transformation. Thus, Stepanyan’s film is a way for the shadows of forgotten ancestors to be revived by the movement of the camera, which can still resonate with us today, decades later. The film is a farewell letter to Soviet times and is also a farewell letter to her father. It is an invocation to make Armenian cinema live again in our memories. And for many spectators, this revival is a discovery.

- Benjamin, W. (2003). On the concept of history. In H. Eiland & M. W. Jennings (Eds.), Selected writings, volume 4: 1938–1940 (pp. 388–400). Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ↩︎

- Boym, S. (2001). The future of nostalgia. Basic Books. ↩︎

- Doyle, A. (2025, May). Tamara Stepanyan on My Armenian Phantoms. East European Film Bulletin. https://eefb.org/country/armenia/tamara-stepanyan-on-my-armenian-phantoms/ ↩︎

Leave a Comment