From the East This Tree’s Leaf Shows

Ildikó Enyedi’s Silent Friend (2025)

Vol. 159 (November 2025) by Anastasia Eleftheriou

Goethe’s botany is the study of the formation and transformation of organic bodies. He sought to identify Urformen (primordial forms), the essential, dynamic patterns underlying the diversity of life. His most famous notion is the positing of an Urpflanze (archetypal plant), according to which all parts of a plant are metamorphoses of a fundamental organ: the leaf. It was Goethe’s belief that these archetypes could not be discovered through scientific analysis (like Linnaean taxonomy) alone. Goethe insisted on a “disciplined perception,” heavily informed by aesthetic appraisal. Science and art, with their corresponding conceptions of nature, are not incompatible but complementary. In the modern Western world, the artist-scientist has rarely found a ready audience. Goethe was bewildered by many of the responses his essay on plants generated among his circle of friends and acquaintances. What was this new effort supposed to be? It seemed too scientific for poetry, but also too poetic for the sciences. “Nowhere,” Goethe complained, “would anyone grant that science and poetry can be united. People forgot that science had developed from poetry and they failed to take into consideration that a swing of the pendulum might beneficently reunite the two, at a higher level and to mutual advantage.”1

The union of science and art, as perceived through the study of plants, is at the core of Silent Friend, the most recent feature of Hungarian filmmaker Ildikó Enyedi (winner of the 2017 Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival with her On Body and Soul). Silent Friend premiered at the 2025 Venice Film Festival. A majority-German production, the film is set in Germany, with the Hungarian director immersing herself in the poetic depth of the German language and local scientific culture. The film invites viewers to question whether the sensorial experiences of plants and humans are really as different from each other as we tend to think. In Silent Friend, this Goethean wish begins to take form, as the film lets botanical research and poetic perception grow into one way of looking at plants and people.

The story is set in the botanical garden of Marburg, a medieval university town in Germany. The garden serves as the backdrop for three stories that span just over a century, each filmed in a different format: 35mm for the early 20th century, 16mm for the 1970s, and digital for the contemporary story. The director explained during a Q&A at the Thessaloniki Film Festival that the three formats were not chosen to reflect the technologies of each time, but the different ways in which people see the world. The first segment centers on Grete (Luna Wedler), the first female student admitted to Marburg University. Grete passes the entry exam to the university by impressing a panel of misogynistic professors who attempt to destabilize her by questioning her on the sexuality of plants. In fact, Enyedi explained at the Q&A that the first-ever female scientist to enter this particular university was a Japanese woman, as the laws allowing women in Germany to study were only changed gradually in the late 19th and early 20th century. Here, Grete might not be the real historical character, but Enyedi turns her character into a symbol of female strength and uses her story to reflect on the discrimination faced by women scientists at the time.

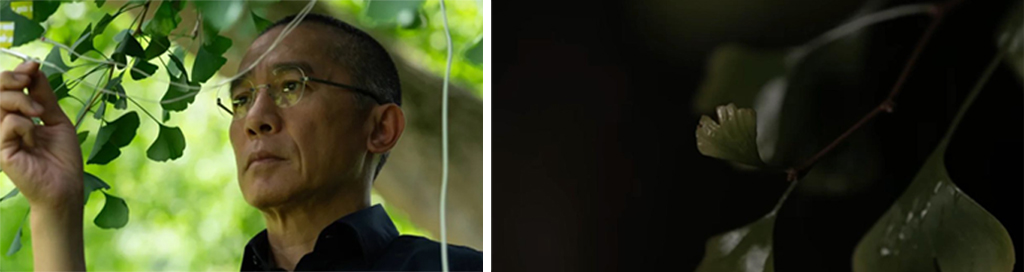

After being accepted to study botany, Grete takes a part-time job at a local photographer’s shop, where she learns to use a camera and develop film. Her subject matter, which she becomes increasingly passionate about, is plant leaves. She develops an interest in their forms and photographs their fine structures in close-ups (Figure 1). Enyedi explained in Thessaloniki that this part of the story was inspired by the work of photographer and sculptor Karl Blossfeldt. In 1928, at the age of 63 and just four years before his death, Blossfeldt published his first photography book, Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Plants). The book’s 120 plates capture different plant species in remarkable detail, almost as if under a microscope, frozen into new forms that lend them an abstract quality (Figure 2). Blossfeldt’s work complements Goethe’s idea of the Urpflanze. In his photographs stems, buds, seed pods, and tendrils are isolated until they shed their botanical identities and appear as elemental structures. Grete’s aesthetic-morphological observations pick up this “disciplined perception,” and due to her being a scientist, establish faith in a re-union of art and science and the idea that perception, wonder, and analytical observation belong together.

A few decades later, in 1972, against a backdrop of social unrest in Germany, Hannes (Enzo Brumm), a shy student, falls in love with Gundula (Marlene Burow), whose research on a geranium introduces him to the language and emotional reactions of plants. This particular experiment is based on real research and explores how plants react, or fail to react, to the presence and actions of people around them. The shy student cares for the plant while Gundula is away on a field trip. When he realizes that the plant ‘reacts’ to his entering or leaving the room, or to his intense movements and playful screams, he becomes obsessed with continuing the experiment on his own. After observing the geranium’s roots vibrate as a response to Hannes’ screams, audiences may think twice before leaving their plants alone without at least bidding them proper farewell.

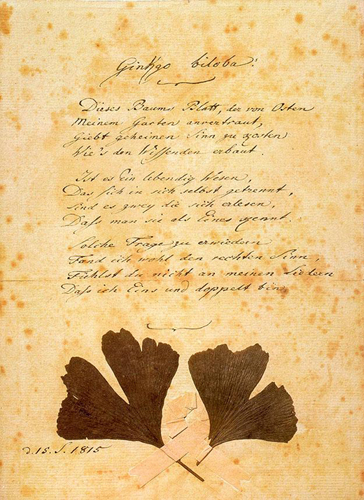

The third segment, shot in digital, brings us to a more recent period. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Dr. Wong (Tony Leung Chiu-wai), a neuroscientist from Hong Kong specializing in infant brain research, discovers the work of Alice Sauvage (Léa Seydoux). Alice is a French scientist with whom Dr. Wong embarks on an unusual experiment (through Zoom meetings), involving a more than 100-year-old ginkgo tree in the central courtyard of Marburg University, now empty due to the pandemic. Dr. Wong’s obsession with studying the tree’s reactions is reminiscent of Hannes’ fascination with the geranium, though at first it seems more scientific (due to his technical equipment) and less impulsive. Little by little, the viewer begins to sympathize with the professor’s curiosity about the tree, who finds common patterns between the flow of neurons and plant growth (Figure 3). Clinical neuroimaging is juxtaposed with tactile close-ups of plants as they swell and open, again synthesizing scientific observation and sensory experience. The film builds a visual and narrative arch around this common experience, which culminates in a scene in which rain falls on the ginkgo tree’s leaves (Figure 4) that is paralleled by Dr. Wong standing in the rain with his eyes closed. Again, we are not far from Goethe’s world, who even wrote a poem entitled “Ginkgo Biloba” (Figure 5), in which the ginkgo leaf is compared to the lyrical speaker, a figure of unity that holds division within itself.2 In Enyedi’s film, the rained-on tree and scientist, are similarly shaped by patterns that cross the boundary between plant and personhood.

The only thing preventing the professor from pursuing his research further is the campus’ moody security guard, who, frustrated by the professor’s daily Tai chi routines and quirky experiments, reports him to the university council for inappropriate behavior. To draw a connection between the first and third stories, we might suggest that both the male researchers in the first story and the German security guard represent the fear of the ‘different,’ and the tendency to protect one’s territory.

For quite a few decades now, the observation of plants has been an ever-growing fashion, from academic research to random YouTubers trying to make a statement about plants’ feelings (in Germany, Peter Wohlleben is the face of this movement). However, in Silent Friend, Enyedi seems to care as much about how people observe nature as she does about how nature observes people. The lens turns around, and we see ourselves from the ‘perspective’ of a plant. Through this experience – this revealing of ourselves – we, just like the characters in the film, gain a sense of how we connect with others.3

Without an overload of academic or scientific detail, the film is fueled by poetry and echoes the delicate line of Goethe’s scientific lyricism: some people will think the film is not scientific enough, hence naïve and sentimental. Others may feel it lacks the full inspirational strength and language of poetry; its stories take paths that never fully converge, and moments of silence and sensory intrigue are sometimes followed by excessive, even didactic dialogue. But for those who choose to look and be looked at by the protective tree, the film reveals that where poetry and science unite, there is a road that leads up to something beyond our conscious understanding. All we have to do is embrace it, silently.

- Goethe, as cited in: Miller, G. L. (2009). Preface. In J. W. von Goethe, The metamorphosis of plants (pp. xxiii–xxv). MIT Press. ↩︎

- Goethe, J. W. von. (1998). Poems of the West and East (J. Whaley, Trans.). Peter Lang. (Original work published 1815) ↩︎

- There is an underlying ‘ecological’ message in the film, despite Enyedi’s reluctance to name it as such. Indeed, even Goethe’s emphasis on the interdependence of organism and environment, as well as organism-to-organism relationships, can be described as ecological, seventy-five years before German biologist Ernst Haeckel coined the term. ↩︎

Leave a Comment