Sequences, whose cinematographic title indicates that this is a movie about a movie, is the only Romanian film depicting the life of its crew, a reason for which it is often compared to La nuit américaine (Truffaut, 1973). Sequences has three parts, each telling a different story, the film crew intervening in each of the episodes. Even though the film is not built on an apparent conflict or a message, the main theme of the movie is to show the crossroad between cinema and daily life. This issue has also been analyzed by Lucian Pintilie in The Reeactment (1968), a movie in which the state authorities, together with a cameraman, are reenacting an incident with the purpose of accomplishing an educational film on the dangers of alcohol for youth.

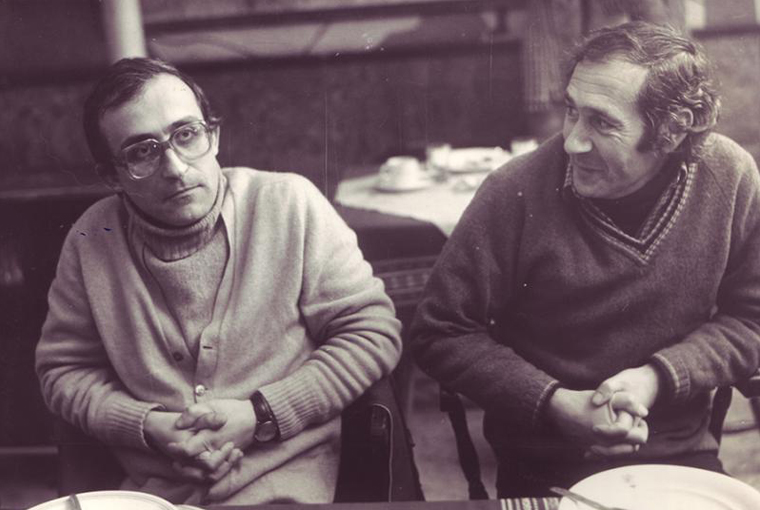

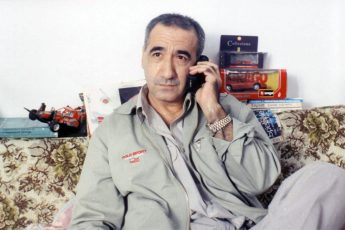

The protagonist in the first episode of Sequences is a young man who has just come out of the hospital and who monopolizes a public phone, calling different friends in the attempt to find company for New Year’s eve. When the film crew shows up, the protagonists are surprised to find out that it is just a mise en scène. We then see the director, alone in his studio, on the 31st, without family or friends, just like the young man at the beginning of the sequence. Played by Tatos himself (the film crew in the movie is also the real film crew of Sequences), the role is a self-portrait of his, but meanwhile a meditation on the theme of loneliness. This apparently non-essential theme makes you think of loneliness as that paradoxical and unacceptable form of the existence of the individual in Communism, a residuum of the official definition of happiness as communal living.

The second part is about the film crew which, at the end of a field day at a factory, stops to eat at a restaurant. The unexpected ironic effect of the sequence is that the factory, a key character of the contemporary films of those days, is making its appearance only casually, thus remaining inconspicious in the plot line of the movie. On the other hand, the crew arrives at a restaurant that has no food, the clients sitting down with their coats on, and the ambience being rather dull. In order to determine who is the man in charge, a member of the film crew passes as a public prosecutor. The boss of the restaurant, a wheeler-dealer person, knows that nowadays you cannot do anything without useful connections; therefore he is servile with the important clients. Gradually, the host starts to confess: we find out that his dream has been to become a bureaucrat, but his wife had left him. Still, he adds, at least he owns a car, furniture and a carpet. This account from “real life” is a new opportunity to access Romanian society of the 80s and to grasp what welfare then meant; a chance to understand what it took back then to eat in a restaurant, and what the dreams of ordinary people were.

The last sequence is about two extras that are discovering a mutual past during the shooting of a movie about the years when Communism was “illegal”. Over lunch, they realize that they had met in the past – one being an investigator, the other one the victim of persecution, though one cannot tell what it is exactly that had gone on between the two. In the end, the story has a subtle and a critical outcome. It reflects debates about the historical grounding of Communism, and the sarcastic effect of the whole sequence is intensified by what is happening in real time with the rest of the team: the main actress doesn’t manage to be dramatic, which leads the director to use all kinds of methods (for instance, splashing her with water). Taking into consideration the difficult context that the film was made in, these these episodes from the making of the film have hilarious consequences, and are meant to suspend the audiences’ belief in contemporary cinematography.

Sequences is one of those Romanian movies which you can watch hoping that you will learn something about Romania of the 80s, Tatos being part of those filmmakers that are preoccupied with likelihood in his movies (for instance, there is a powerful contrast in Sequences between the official way of speaking, and the language of the streets). Also, it can be said that Sequences is a film in which Tatos exteriorizes the perception of the filmmaker’s status as viewed by the Communist authorities – directors perceived as functionaries rather than artistic individuals (thus, his position is constantly disputed and derided by members of the crew).

Seen from today’s perspective, the movie functions as a deconstruction of the whole Romanian cinematography during Communism, a disenchantment of the filmmaker’s role of that time, and as a complex questioning of major accounts such as truth/lie, reality/fiction and everyday life/extravagant filmmaking. Nuit américaine indeed, but à la Roumanie…

I saw this film years ago at an art-house cinema in LA and I’ve been trying to find it again ever since. Do you know if there are any plans to release it as a DVD?