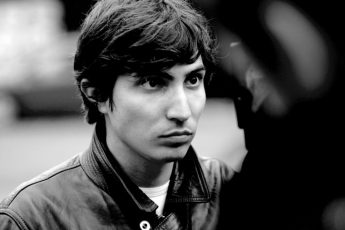

Cristian Mungiu speaks about his latest film, Beyond the Hills, which is in this year’s competition of the Festival de Cannes. The film revolves around a troubled woman who returns home from abroad to seek help from an old friend…

Did you feel pressure making a film after the success of 4 months, 3 weeks and 2 days?

Of course, there was great pressure resting on me. Many people thought that after I won the Palme D’Or my next film would automatically be accepted in Cannes. But it’s not like that. You have to start from the beginning again, and convince the committee that your new film is special, too. And that was the real pressure: trying to live up to the expectations. It is nice to be popular, but I had to accept that it would be more difficult to make my next feature.

The plot of your newest film is closely tied to questions of religion. Could you say something about the current situation of the church in Romania?

During Communism in Romania, the Orthodox church was tolerated. It was not popular, but neither were people prevented from going to church. After the fall of Communism, the Church became very popular, building around 4 000 in the last 30 years, so that we ended up having around 20 000 churches for a population of 30 million. What I wanted to show in my film is that for a religion that is so widespread, the impact on the life of normal people is not so visible. I think that there are benefits in religion that should be encouraged, but it many ways religion in Romania has been reduced to rituals and routines. I think that anything – including the church – should be questioned. Having said that, I do not see my film as being critical towards religion.

What is your personal connection to religion?

I do have a personal relationship with religion, but I don’t like to take things literally. I believe in values, values that are neither confined to nor invented by religion.

What is your story about?

It is a true story, a story that is in large part described in the non-fiction novels by Tatiana Niculescu Bran. Personally, I wanted to investigate this situation where guilt is imposed on someone by others. Again, I am concerned with saying that religion should not be taken too literally. If you think that all things that religion teaches should be taken so literally, then religion loses the essence of its teachings. If you want to say that the devil exists, you should recognize him in your ignorance, intolerance, and indifference towards others.

In fact, I am not so sure this material is truly suitable for cinema. There are things in life that are too complex for filmmaking. As a filmmaker, you have to try to break up the complexity of the event and fit it into a movie.

Do you think there is a difference between political and religious intolerance?

Of course, intolerance can have political and unpolitical aspects, but its intolerance all the same. If you are intolerant, you are not able to listen to the opinions of others, and you think you know better than them, so I don’t see a great difference between religious or political intolerance and intolerance in general.

The real cruelty that the community in the monastery commits is that they put this idea into Voichita’s mind that, in the name of God, she must give up all the love that she felt before she arrived in the monastery. I don’t think that God himself would ask something like that from anyone. It is again a mistake that the church as an institution commits. It is okay to have personal faith, but you must use your own experience to exercise it correctly. I am not speaking out against religion. My main concern with religion is that the church does not exercise its power properly.

Do you think that society is more to blame for the death of Alina than the monastery?

This is the view of the websites and journals that reported on the incident from the perspective of the Orthodox church. We have to admit that all the social institutions involved in this case were trying to do something. This is precisely why it is so hard to take a stance and determine who is guilty.

What do you think was the impact of Communism on moral values in Romania?

People on the countryside used to live in peace together because there was a sense of community. It was common sense that people should respect one another, a stance partially caused by religion. During Communism, this respect and trust in others disappeared. People from the villages began working in factories in nearby cities, and the basic education and moral values from the church they were receiving on the countryside were replaced by nothing at all.

What kind of reaction to your film do you expect from the Orthodox church in Romania?

They were not very vocal about this topic. I know that they were okay with the books by Tatiana because they document the truth without condemning anybody. What I do hope for my film is that the church and viewers in general won’t form an opinion before seeing the film…

Leave a Comment