Timid Attempts at Magic Realism

Elçin Musaoğlu’s The 40th Door (40-cı qapı, 2009)

Vol. 54 (June 2015) by Moritz Pfeifer

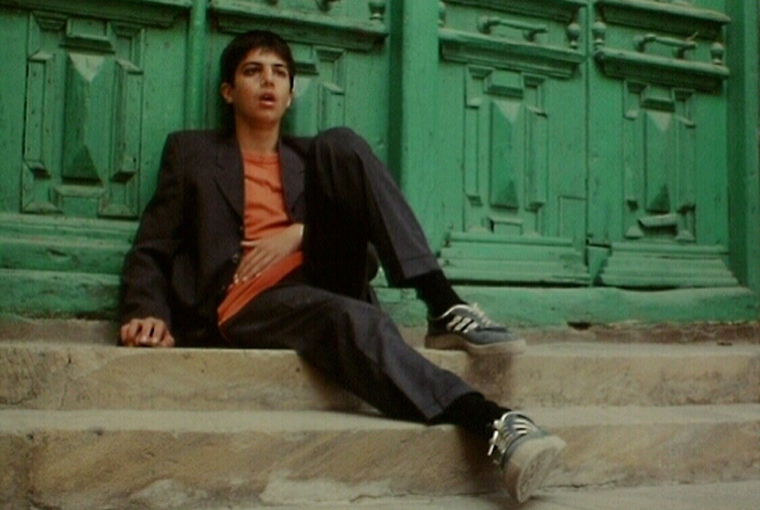

Elçin Musaoğlu’s 2009 feature The 40th Door tells the story of Rustam (Hasan Safarov), a young boy living in modest conditions on the outskirts of Baku. When his mother receives a phone call from Moscow telling her that her husband has died, Rustam is forced to find a job in the city to take care of her.

Upon his arrival in Baku, he starts working at a car wash, which allows him to send some money back home. He stumbles across a drum band and begins to dream about becoming a musician. But the city also leads him into darker alleys. When he starts hanging out with hustler Edik (Rousan Agayev), they end up breaking into the homes of Baku’s richer suburbs. Later a gang of thugs begins to threaten Rustam, asking for pay in exchange for his right to work in peace. When the gang steals his Nagara, a drum Edik gave to him, he returns home beaten and with plans of revenge.

In portraying its protagonist’s loss of innocence, The 40th Door follows a classic neorealist recipe. Rustam sets off his journey with good intentions and is forced to sacrifice them for survival. Initially, he wanted to prevent his mother from selling a valuable rug to foreign buyers, which had been in their family for generations. True to the neorealist traditions, Musaoğlu includes a strong social element to his story. Thus Rustam’s moral downfall is less perceived as individual-psychological than as socio-political. Already the first scene makes it clear that corruption is a social norm. During a casual soccer match, Edik tries to motivate the losing team by promising them an expensive watch. In general, practically everybody in The 40th Door takes part in some kind of shadow economy – selling century-old rugs to connoisseurs, cleaning cars, or working in a “brick-factory” run by children.

Certainly, The 40th Door can been seen as a “stripped-down neorealist fable” (Peter Debruge for Variety) in the style of De Sica. But there are also fantastic elements to his film. It is difficult to ignore Rustam’s dream, for instance, in which he sees himself stabbing his own father. The scene also foreshadows Rustam’s revenge spree and the biblical “Father, why hast thou forsaken me?” that closes the film, which he utters while stabbing a streetlamp. These symbolical, indeed, psychoanalytical references are certainly not in neorealist tradition. Although scarce, they bring the film closer to the culturally-imbedded magical realism of, say, early Kusturica movies than to the recent realist upsurges of Belgium, Romania or Iran.

The film’s title, at least, suggests that The 40th Door is more myth than reality. It refers to a local legend in which a hero rescues a princess from a castle with 40 doors without ever having to face the obstacle inside the last room. With its rich, ancient, and multi-ethnic cultural traditions, Azerbaijani cinema would definitely have enough resources to direct its cinema in a more magical direction. In this respect, it is regrettable that more recent Azerbaijani films, while often lamenting the loss of cultural traditions in contemporary society, have not found the formal means of bringing them back to life.

Leave a Comment