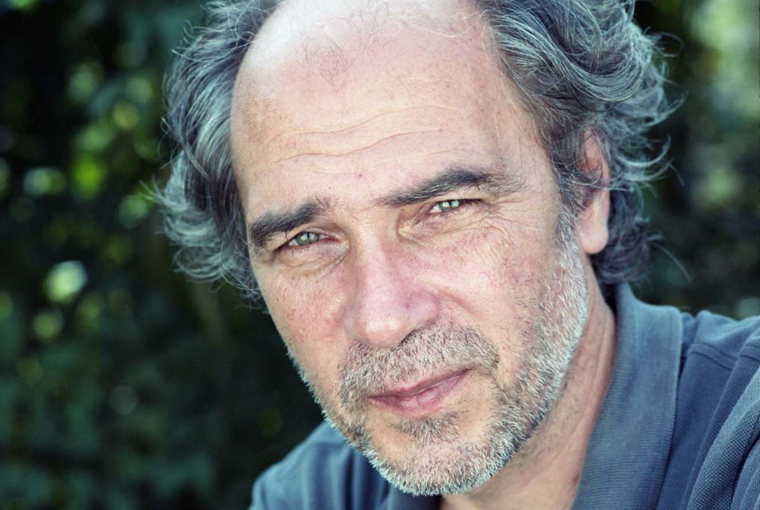

On the occasion of our special issue on Ukrainian Video Art (May ’20), we sat down with filmmaker Aleksandr Balagura to speak to him about the themes and aesthetic ideals ranging over his work. Balagura also speaks about his ambivalent relationship with Ukraine and Ukrainian cinema, and the limits of national categorization.

Why did you start making experimental cinema? Was it a way to avoid the classical narrative form?

If, by the term classical narrative, we are referring to works such as The Iliad or The Odyssey, Gogol’s Overcoat or Die Legende vom heiligen Trinker by Joseph Roth, La passion de Jeanne d’Arc by Carl Theodor Dreyer or Un condamné à mort s’est échappé ou Le vent souffle où il veut by Robert Bresson, or even À bout de souffle by Jean-Luc Godard, I would say that there is no need to avoid this form of artistic narration.

Moreover, according to an ancient Chinese proverb, “there are no marked paths along the way”. It’s a question of language, artistic language in particular. A sincere phrase uttered in a certain way and in a certain moment can be false if repeated at another moment. When we make a film, we are always searching for the “right words”, the authentic intonation, for that one path that corresponds to our vision and our sense of the world. This leads us to make our own film and not a copy or parody of something that already exists and has already been made before by someone else, and is therefore a fake. Then some of our choices can be defined as traditional or innovative, classical or experimental, successful or not. “The one who walks is lonely and in peril,” the Chinese saying continues.

The fact is that every work of art, every film, is always a new path. It has not been “traced” and therefore it is dangerous, and the director always takes it in solitude. It’s like in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Zone. Stalker, the protagonist of his eponymous film, says to his travel companions: “The Zone is a very complicated system of traps, and they’re all deadly. I don’t know what’s going on here in the absence of people, but the moment someone shows up, everything comes into motion. Old traps disappear and new ones emerge. Safe spots become impassable. Now your path is easy, now it’s hopelessly involved.” It is a journey, “in solitude and in danger”, but it is the only way to reach the Room where wishes are fulfilled. Except that, unlike the characters in Stalker, who ultimately have the choice of whether or not to enter their Room, in order to make our film, we must necessarily enter our Room. The name of this Room of ours is the Editing Room.

Cinema is editing, says Jean-Luc Godard. But not all editing is cinema, at least if we understand cinema to be art. And every time we have to find that right edit, that living and therefore true language that allows us first of all to understand our questions (even the most profound ones, on the enigma of the world, on the meaning of our existence – why not?), to then be able to pronounce them, to share them with others and thus to be able to find that path that will (maybe) lead us to answers. Again, as always, it is a path, a journey. A journey within ourselves and through ourselves towards a goal, distant lands, the limit, beyond which we never know what is there. (Treasure? An ideal? Artistic beauty or scientific truth? Love? The answers to our questions? Anything?) We then return to ourselves and leave the Room as we really are and with what we deserve. It is a necessary journey, one that can last a few days or our whole lives. “The straight path is not always the shortest,” says Stalker. It is always a miraculous journey, because cinema is a miraculous art, and because otherwise you cannot leave, much less return.

Are you familiar with contemporary Ukrainian films, and experimental cinema being made in Ukraine? How do you understand these films, relative to the Ukrainian cinema of the past? Is there something that constitutes a “Ukrainian cinema” for you these days?

I cannot say that I know contemporary Ukrainian cinema well. I know that many films are produced, but I only know a few of them. The fact is that today’s Ukrainian cinema is largely influenced by politics and by an ideology I don’t agree with. It is not only influenced, but also conditioned and controlled by it. In this sense, I feel alienated by the phenomenon that could be called “contemporary Ukrainian cinema”, at least by the official “mainstream”, which was created in 2014, when nationalism took over the country’s political and cultural life. I believe that the current cultural policy in Ukraine makes the existence of a truly free, nonconformist and independent cinema very difficult. Of course, even within this context, there are skilled and talented authors who make ideological and political choices in their films, and in the end the choices are always moral, ethical and, I hope, free. However, I also grant myself the freedom not to share them and not to accept them. As a consequence, it makes it difficult for me to talk about the artistic aspects of this side of Ukrainian cinema.

In a work of art, aesthetics and ethics are indivisible. In this sense, my preferences have remained with the Ukrainian cinema of the past, with the cinema of Alexander Dovzhenko, Leonid Osyka, Sergei Paradjanov and certainly of Ivan Mykolaychuk with his film Babylon XX and his character of the Philosopher, whom I consider the key character and custodian of the conscience of Ukrainian cinema and culture, and who thus far, even in these times, represents the sense of the phenomenon of “Ukrainian cinema”, as its soul and its image.

Regarding experimental cinema, understood as a freshness of gaze, freedom and finesse of the artistic language, I would nominate Anatolij Syryh, a splendid director, a wonderful person and a dear friend of mine.

And how about Ukraine in general, are you influenced by its society and events that occur there?

It is a very painful topic for me and is becoming increasingly so over time. It is reflected in my films. I think I have already partially answered this question above. I would just add that I understand the aspirations of Ukrainian society towards its future, towards a free, democratic and independent country, but I cannot share and accept the ideological approach chosen for this path, which is based on the total negation of its past (obviously I mean the Soviet period, its demonization and often also its falsification) and, above all, on nationalism. I don’t mean to say that the majority of Ukrainian society supports nationalism as such. In fact, election results usually give the nationalist wing parties very few votes. Nonetheless, Ukrainian politics in general, and cultural policy in particular, are openly nationalist, determined and conditioned by the active nationalist minority.

The national and cultural politics of a state and nationalism are not the same thing. Nationalism is like a chameleon. It camouflages itself; it presents itself in various guises but it always uses ideological tools and political methods, and inevitably transforms itself into an instrument of power and political manipulation. It is anti-cultural, because it is limiting and suffocating for the culture of the people it believes it represents. It is undemocratic because it proposes itself as the founding principle of social unity, and the criterion for the individual’s sense of belonging and adequacy in relation to society. It’s a long story and that’s why I haven’t lived in Ukraine for over 20 years. I don’t want to go into detail. In fact, discussions that started with friends many years ago have never ended. Maybe because “the devil is in the details”? Over time we have learned to avoid certain themes and topics as the only way to preserve our friendship. Perhaps it’s better that way. Perhaps it’s better to let time be the judge. Perhaps. It’s a shame that the same rushed time transforms our shared present into an increasingly less and less shared past.

I know that I will be challenged by the majority of the people who read these lines, especially those in Ukraine. But let’s be patient. “The flesh induces us to say I and the devil induces us to say we,” writes Simone Weil in the book Waiting for God.

If you make these kinds of statements in today’s Ukraine they may say: “Suitcase. Station. Russia.” In fact, that’s what I did in 1998. Except that I found myself in Italy instead of Russia, where at the time (as in in all the ex-Soviet countries) the same economic and cultural looting that is still continuing in Ukraine today was going on at full speed.

How about Italy, what did you want to say about Italy in Pausa Italiana and Life Span of the Object in Frame?

What can I say about Italy? Maybe that it has become my home. I discovered it in 2003 when suddenly I realized that “I go” to Kyiv and “I come back” to Italy. It is not a new home, but it is still my home. Has the view from the window changed? The views from all windows change over time, and sometimes become unrecognizable. Here old and new objects, memories, friends, and books have become mixed. The small bronze bust of Pushkin that came from Kyiv stands next to that of Dante. They seem to get along fine together. From here you can still reach the cafe in Zan’kovezkaja street in the heart of a Kyiv from the 1970s-1990s, and editing room No. 2 in the documentary cinema studio. In a new Kyiv, this is now impossible. I have tried in vain several times. From here, I can still take that night train that takes me, as it did in the 1960s-1990s, from Kyiv to Debalzevo, a railway hub and a necessary stop on the way to Nikishino, a village 18 kilometers further on, where my grandmother lived and where I spent my childhood summer holidays. The names of Debalzevo and Nikishino were not known by anyone at the time. They were my intimate territory, hidden in the depths of my memory and heart. And they still are. Italy allowed me to keep all this, the images, the voices, the time, to preserve my homeland…

Perhaps this is what I meant in the films Le battement d’ailes d’un papillon and Life Span of the Object in Frame. It wasn’t the only thing, but it was definitely a part of it. The last time I was in Debalzevo was in 2012. In the station entrance there is still a naive post-war painting: “The liberation of Debalzevo from the Nazi-Fascist occupation”. The painting shows the destroyed station with a lot of fire, weapons and Soviet soldiers. In the center, one of the soldiers is embraced by a girl who has probably been waiting for him for a long time, for the whole war. I filmed this painting. I filmed that embrace between the girl and the soldier, the destroyed station, the fire, the weapons… Then, in 2015, Debalzevo and Nikishino found themselves on the front pages of the newspapers because of the armed conflict in the Donbass. Maybe I shouldn’t have filmed that painting. Maybe I should never have gone back there.

The Italy in Pausa italiana is a kind of limbo-Italy. It was 2003, my fifth year in Italy, and I needed a film. Antologion, my last Studio film, was from 1996. I lived with my wife and three children in a small village in Abruzzo, almost on the border with Lazio, where time and its flow were perceived in more of a circular than linear way. This is typical of life in small Italian towns. It is like being in a glass sphere with a medieval image of the world depicted inside, like a flat Earth floating between the vault of heaven above, and the underworld. It’s like being in a kind of limbo. The film is the experience of following the life of this limbo, together with my own life in it, from inside and outside this sphere.

It is a very special film to me. It was proof that I can’t not make films. It was also my first experience of making a film digitally, and also of freeing myself from the snobbery of celluloid, which had been left over from my time working in the film studio, and of reflecting on the nature of digital as the cinematographic material. It’s called “Pausa italiana (film sull’attesa del film)” [“Italian Pause (A Film on Waiting for a Film)”]. It lasts four hours. It was a long wait. It is the film that marked my transition to personal cinema. In Antologion, I put my breath into the chest and mouth of the Philosopher, the lyrical hero and the leitmotif of the film, and in Pausa italiana I am present physically and with my voice. At the time, I was reading Ezra Pound who consequently became part of the film as a poetic guide.

In this film you talk about Nietzsche living in Genova, Dante, Cervantes, Shakespeare and Russian poetry, as well as reflecting on the nature of metaphor. Do you owe an influence to literature or to major writers of the Western canon?

A true work of art is always universal and in this sense international, as are science and culture in general in the modern world. By asking universal questions, a work of art goes beyond the national, it “transcends” other cultures, becoming part of cultural realities and people’s experiences.

When we were young, as students, in addition to being cinephiles, we were all insatiable readers, and we went to the film club with books in our pockets.

Dante, Pirandello, Nietzsche, Homer, Henry Thoreau, Mayakovsky, Vysotsky and Karabut, who are part of Life Span of the Object in Frame, together with many other authors, intersected with the sequences of the films seen and the films shot, with the images of the city, the voices, the phrases, the faces, the glances of friends and of unknown people, of the mother. They were and are part of reality, of experience, of life. At the time they constituted a world, a true homeland, a shore of departure.

How about found footage? In Antologion and Life Span of the Object in Frame you use this medium. To what end?

Photographic and cinematographic images made by someone else are part of the reality that surrounds us, of our experience, memory and imagination. They influence us, they determine our choices. They are events in our life that equal the “real” ones. And when they become the material of our films, they transform into our images, together with the “real” events. They are “pronounced” by us with our voice, intonation, accent.

“Antologion” comes from ancient Greek, meaning “collection, bouquet, wreath of flowers”, or even “collection of the lives of saints, of poetic passages”. My film was created as a tribute to the centenary of cinema. It is a montage film, the genre that established itself in the 1920s, at the time of silent cinema. In fact, I edited it like a silent film and only after reviewing it in its entirety and realizing that it works did I add some noises and music by Avet Terterian and Valentin Silvestrov. Antologion is a cine-rhapsody founded on fragments of classical films produced in Ukraine during the Soviet period. I wanted the themes, characters and images of these films from various authors and years (which were often ridiculed and in this sense “buried” by critics) to recall, intertwine and communicate with each other, to take strength from one another and become current again, acquiring a new metaphor. I don’t know if I managed. As the years pass, I have the impression that I did. Meanwhile, the gazes of Dovzhenko’s characters met with those of Mykolaychuk, and together they look towards the same sky, where Paradjanov’s star shines.

The idea of Life Span of the Object in Frame arose from my interest in the phenomenon of photography and its enigmatic enchantment. Hence the title, which, on the one hand, is almost the technical definition of the exposure time in the photographic process, and, on the other, opens up the perspective of seeing a photo not only as a two-dimensional graphic image, but also as a container of time. The photographic images of the 1960s-1990s and early 2000s by Yevgeny Pavlov, Aleksandr Chekmenev, Aleksandr Ranchukov, Vladimir Kukorenchuk and Anna Voitenko are also their memories. In the film they become mediums that use air, light and rhythms to provoke our recollections, to help us to find our “lost time”, to repair that “thread that binds times”, and in this way they themselves become part of our memory.

But that’s not all. When we take a picture or are shooting something, we are never aware, we never fully know what we are actually witnessing, the true meaning of what we are witnessing and what we are capturing. This situation relates to the famous “flapping of a butterfly’s wings”. About 20 years ago, Aleksandr Chekmeniov randomly took a photo depicting a girl sleeping in broad daylight under a shoal of fish in Privoz, the famous market in Odessa. He did not know the girl and did not consider the photo to be one of his most successful. One day he showed it to me. The photo enchanted me. In my eyes, it became “La Dormiente al Mercato” (“The Sleeper at the Market”), one of the most important images of the film we have just started working on. On the first day of filming, we were at the Odessa market with the photo in hand, looking for the exact place where it was taken. Suddenly, someone recognized the girl in the photo and told us the story of her life and death. The film changed. The romantic Dormiente al Mercato from the beginning of the film eventually turns into the metaphor of my country, of my homeland, who fell asleep and then was raped, cut, sold off in pieces, found one morning dead of cold and buried no one knows where.

The use of found footage is a very interesting topic. A photo re-photographed or reproduced in a film is no longer the same original photo, rather it changes, it becomes the object of the shoot, a new image. Images that contain other images in themselves are captivating. There are some famous examples in painting, photography, cinema (remember Godard’s Anna Karina watching The Passion of Joan of Arc) or poetry, when a quote is no longer such, but becomes the organic material of the text of a work, such as in the work of Ezra Pound, or in modern art collages.

There is also another very interesting aspect of using photographic material as cinematographic material I would like to talk about. A printed photo (and before the arrival of digital this was always the case) is also an object, and as such it can be manipulated: looked at for a moment or for hours, turned, thrown, torn or lost. When it becomes the material of a film, however, everything changes. Once it is placed on the timeline, it turns into a pure image. But the real mystery begins later, when the “play” button is pressed, when Time starts. You look at it and you cannot break away, you are waiting for something. You understand that nothing can change, nothing can happen, but still you wait for something to change, for something to happen. And in reality something is happening, something truly mysterious, the mystery of mysteries: time is happening, represented by this image and by ourselves. We can press the “stop” button, but the feeling remains.

There are passages of chronophotography in your films. What does it mean for you to have chronophotography? The slow-motion image of a bird flying seems to be your signature, we can find it in a few of your films. Would you agree?

I have been fond of the work of Eadweard Muybridge for many years. I got to know it when I was just 20 years old. Between 1994 and 1995 I rented a room in the studio where I worked, and a small group of friends and I started working on the project Il Secolo D’Oro (The Golden Age). We worked using analogue. We did a great job but the project didn’t get finished because the money simply ran out. I still have the tests that we made of the rhythm of movement in the Muybridge sequences, which we carried out on 35mm film. This material also included the sequence of Plate 755, Pigeon Flying. I used it for the first time in Antologion as an image of cinema, of the soul of cinema. From that time, Muybridge’s Pigeon has continued its flight in my subsequent films.

Imagining the world of cinema as the human world, that is, as a world that is created, generated and multiplied, Muybridge’s characters would be its first inhabitants, like Adam and Eve, or like the ancient Greek gods. They are immortal, because their time is circular, as are their movements and actions. The Golden Age belongs to them. The arrival of film with the Lumière brothers marked the beginning of linear time, and the spell was broken.

I use Muybridge’s sequences in my films as Platonic ideas, archetypes of movement.

It seems the motifs of the window, of the frame and of the gaze – if not of photography and of the ‘still image’ – were important to you in a few of your films. What did you want to show with the metaphor of the window/frame (especially in Life Span of the Object in Frame)?

Since art is physically handled by people and not gods (who can help them, inspire them or even use them as tools of their own projects in fortunate cases), then, despite not having the opportunity to represent the whole world, they are forced to use a frame as an artistic method to represent or tell it through a part of it, cutting it out from the whole, and creating a miniature model of the world.

The image of the window is a version of the frame, the humanized, personal, intimate version: a house, a shelter, an inside and an outside, the self and the world, the eyes, the gaze. It is one of the most enigmatic and attractive images in art. It expresses the human condition in the world and is directed not only outwards but also, and especially, inwards. It is widespread in mystical and secular, classical and modern art, from the most extreme examples such as the Shakespearean “I could be bounded in a nutshell, and count myself a king of infinite space”, to Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window. The views from our windows tell a lot about us and our moods, expectations and dreams. They are a kind of self-portrait. They assume a long, silent gaze, a fixed shot.

What did I mean with the images of the window and with the images and static shots? The window and the static shots in Pausa Italiana are a kind of attempt to feel the passage of time, of waiting. Perhaps there is also an echo of this in the windows and in the static shots of Le battement d’ailes d’un papillon, but as an attempt to recognize the time that has passed in the present.

The fixed shots of Loli Kali Shuba are the gaze into the window, the fatally external gaze from outside, which in the end can only remain a gaze. The windows and static shots of Life Span of the Object in Frame are perhaps a sign of internal discomfort, the desire for a pause, for internal calm, to fill the sense of guilt by hiding it behind a cliché image.

How about Tarkovsky. You made a film that somewhat resembles the themes of Nostalghia. Is he an influence for you?

Tarkovsky is a great artist, and his influence is the same as the influence of the masterpieces of literature, poetry, or painting. His cinema is personal to many of my generation.

Tarkovsky is perhaps more present in Le battement d’ailes d’un papillon than in Pausa Italiana. He is present as Andrei Tarkovsky, together with Santa Caterina and Michelangelo, as a memory and a fact of my personal life.

To Our Brothers and Sisters resembles somewhat Artavazd Pelechian (especially his film We), for whom the theme of burial was recurrent. Was he an influence for you in the way of dealing with national mourning?

I met Artavazd Peleschian in 1991 in Florence, after making To our Brothers and Sisters. I didn’t know his films before and I was impressed by The Seasons. He gave me his book My Cinema, where I found some correspondence with the editing of Widow Street, which I had presented in Florence that year.

To Our Brothers and Sisters doesn’t only address national mourning. I was interested in this contrast between the emotional power of the event and the “simplicity” of the physical actions of the rite, which are summed up in a tear.

You made two films about Roma, Loli Kali Shuba and Widow Street. Why this subject?

In Russian culture and art, Roma have always been represented with a romantic tone, which has become a kind of cliché, linked to ideas of freedom and beauty. In actual everyday life this cliché is inverted. There are people in between these two clichés.

Widow Street was made in 1991. The film has been shown on various occasions but the characters, as often happens in documentary cinema, have never seen it. Some of the characters were children. One of them sang a song that I used in the film without knowing the translation, two others followed us by running in the snow when we were leaving. Children are always sincerer, more natural and more affectionate than adults. I was plagued by a kind of guilt. Loli Kali Shuba is the return to the same places after more than 20 years. I screened the old film and found the two “children in the snow”, who told us about their lives during these 20 years, and the “little boy” who sang to us in the old film, who finally translated his song to me. That’s it. The sense of guilt has not passed. I don’t know what to say. I went to film the “last” of this reality, which is very complicated. These people really exist and are beautiful. I asked them what beauty is in their opinion and they answered “the world”.

One is in color, the other in black-and-white. Can you talk about the use of cinematography and color in your films?

The question of whether to use color or black-and-white is always an artistic choice, but in my case it is usually “suggested” by chance, by the circumstances of the work, the material.

The black-and-white of Widow Street was not a choice. The film was not in the studio’s production plan and in a sense it was shot in a clandestine way. The cameraman and I went to present a topic to the editorial board of the newsreels, which were usually in black-and-white, and we tried to save some film, then we went to the Roma camp. Then I showed the material to the studio and got the go ahead for a short film.

To tell the truth, I am very skeptical about the “conscious” use of color and its manipulation, even if the history of cinema proves otherwise. In this sense I am not free. I have a kind of fixation with the original, “primordial”, “virgin” image, as it is made by the camera. Usually I get used to the “original” image very early on and I have difficulty making the decision to change it. Even though I end up doing it sometimes, it’s always an ethical choice for me. Maybe it’s nonsense, but that’s how it is…

Since we are conducting this interview on the occasion of a special issue on Ukrainian video art, it makes sense to look especially at Antologion. You stated that you were interested in teasing out a distinctly Ukranian form of narrative, poetics and cinema through these fragments of Ukrainian films. Is this and idea that you still think about? How has your understanding of what “Ukrainian cinema” is changed, or evolved or persisted, since you made that film?

Ukrainian cinema, and beyond, had already changed at the time of Antologion. In fact, the dedication at the end of the film says: “To the happy people who are gone”. One era was over and another was about to begin. The film was a tribute and a gift to an outgoing form of cinema.

In Antologion, I tried to highlight the main myth of Ukrainian cinema, which for me was the myth of lost paradise and the need to sacrifice things to find it. I still think this is the main thread that returns and resounds in various ways and through various stories, like an echo, in the most important Ukrainian films of the time, and it binds them into a single phenomenon of Ukrainian cinema.

Many of the film fragments in Antologion are not wholly endemic to the country — some by non-Ukrainian-born directors (Paradjanov, for instance), many produced by Moscow. They are Soviet-era films; Ukraine, as a country, is porous. These films are also part of what was called the Ukrainian poetic school. What relationship with the Ukrainian poetic school did you want to pursue in Antologion? Was it like a postmodern reflection on the way the Ukrainian poetic school experimented with form within a nationalistic subject? Finally, what do you draw from Dovzhenko and Paradjanov?

Antologion uses fragments of 18 Soviet-era films produced in Ukraine, plus a few short clips of Soviet documentaries (such as the launch of the first spaceship) and those from Nazi Germany (e.g. Nazi troops in Ukraine). Ukraine was an integral part of the Soviet Union, and it is impossible to represent its history and cinema out of this context.

For example, Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, as well as his The Eleventh Year, were produced in the Kyiv film studio of VUFKU (Ukrainian National Film and Photography Agency), and most of the shooting was done in Ukrainian cities. While working on this film, Dziga Vertov lived in the same hotel as Alexander Dovzhenko, who was working on his masterpiece Earth at the time. Paradjanov was an Armenian born in Georgia who lived and worked in Kyiv and created masterpieces of Ukrainian, Armenian and Georgian cinema. The beginnings of his famous and unrepeatable aesthetic, which flourishes in the colors of his films, can be found in Dovzhenko, in the great black-and-white film Zvenigora, in the episode ‘The Fairy Tale’, which represents a kind of film within the film. I have not yet heard any critics discuss this. Zvenigora is a masterpiece that deserves to be studied. Soviet cinema was multinational, for better or for worse.

I don’t think I’m especially influenced by Dovzhenko or Paradjanov’s cinema. They are just two geniuses. Perhaps Paradjanov is one of those who set an example for me to do what I feel and how I feel it. In the end, I think he is. I don’t think I belong to any particular school, trend or national film context. I don’t know if that’s a good thing or not. That’s just how it went. I love Jean Luc Godard, Otar Iosseliani, Jean-Marie Straub, Federico Fellini and Ingmar Bergman very much.

And you’ve made many more films about Roma communities, marginal or out-of-the-way peoples. You yourself live abroad. Nation, borders and belonging clearly don’t always perfectly overlap in your work. In making Antologion, where do you find or locate this Ukrainian sense or essence? (In people, place, form?) And notably, how do you understand your own films, made abroad, in relation to that sensibility? Do you make “Ukrainian” films?

In Antologion, and beyond, I find the Ukrainian “sense” or “essence” in people first and foremost. Some of these have given an example of honesty, others also of wisdom; some transformed in the lines of their poems or their films. Before starting work on Antologion, I went to the cemetery where Ivan Mykolaychuk is buried, to speak to him and to ask for his blessing for the film. I went by myself. I have only told a few people this story.

I don’t know if I make Ukrainian films or not. I don’t ask myself this question. I was born in Ukraine as a native speaker of Russian and I have lived in Italy for more than 20 years. In my films, the protagonists speak in Russian, Ukrainian, Italian and French. Gogol was born in Ukraine and he wrote Dead Souls in Italy in Russian. It happens… “We need to keep making films… That’s it,” says Jean-Marie Straub.

What are you working on now?

I’m currently finishing a film dedicated to the art of Alain Fleischer.

Then, a few years ago I finally went back to my old film project based on the work of Eadweard Muybridge. I am preparing the material. I work alone, and it takes a long time because of that. But I seem to be at a good point…

At the same time, I’m working with a group of friends on the first edition of a new international film festival: FLIGHT – Genoa International Film Festival. It should have launched in March, but due to the current situation we postponed it to October. Hopefully we will manage.

Thank you for the interview.

Leave a Comment