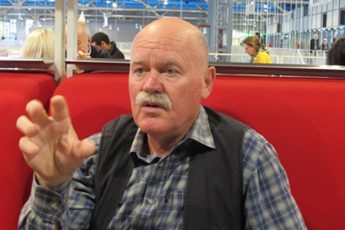

We met Croatian filmmaker Ivan Ramljak at DOK Leipzig (8 October-15 October), where his latest film “El Shatt – A Blueprint for Utopia” screened in the event’s International Documentary Competition. The documentary revisits the all but forgotten story of a Yugoslav refugee camp set up in El Shatt, Egypt during World War II. Ramljak reveals the challenging process behind researching and dramatizing such a complex and neglected topic, and how the stories of the refugees of El Shatt have been suppressed and ignored.

What’s your connection to El Shatt? Did you know about it growing up or is it something you discovered later on?

My family is from Dalmatia. It’s a very Dalmatian story and because my grandfather was there, I knew about the story since I was very young. However, my grandfather died when I was one year old, so I wasn’t so close to the story in the sense that most of the people who were there and are still alive are, the ones who keep repeating these anecdotes to their families all of the time. Still, I knew the basic information. And then, seven years ago, my grandfather’s brother died and his family found my grandfather’s diary from El Shatt in his apartment. And that was the starting point.

The diary is very brief, it has maybe 30 or 40 sentences in total. It’s all everyday writing, it’s nothing heroic. It’s nothing spectacular. It’s everyday life, but in a refugee camp on the other side of the globe. So I wanted to tell the story, but not using a historian’s perspective on the events that unfolded there. I wanted the story to be told by the people who were there, and I wanted them to tell me stuff that they had experienced firsthand. I didn’t want to have this hearsay kind of narrative or a historian’s narrative. I wanted real people telling me things that they had really experienced.

And then I started pitching the idea. When I have an idea, I always pitch it to my friends and colleagues. My goal is to see if it sounds interesting to them. And then I realized that 90% of people don’t know about the story. This includes everyone younger than 40 and everyone who is not connected to Dalmatia. And then I realized that I need to tell it, because for me, it’s a story about unity. It’s a story about this Socialist utopian community. And in today’s Croatia, in our society today, the party that’s been leading the country for almost all of the 30 years of independence has been trying to block the spread of any kind of information about Yugoslavia and especially about the positive sides of that country. So for me, it was very important to tell the story.

Was it difficult to find people to interview? What was your process for getting in touch with them?

You know, when you’re making films about subjects like this – I mean subjects that people really care about – it’s very easy. Because as soon as you spread the word that you are researching that, all these angels, lots of people who I’ve never met, would start sending me information about survivors who are still alive. And so this little network was built out of nothing. And I was getting lots of information. I was searching for people who were a bit older while they were in the camp, because the people who were very young have very similar memories. All the male kids were just talking about how they tried to find something to make a football with. And all the girls were saying how they knitted things with their mothers and stuff like that. So I tried to find people who were at least ten years old at the time they were in the camp. So that meant they would be at least 88 years old at the time when I was making the film. But a lot of them are still alive.

The problem was that I was doing these interviews during the worst part of the Covid crisis. I did my first interview, and then the first lockdown was announced. And then I waited for a couple of months and some people died during these months because they were 92, 94 years old. And then when the first lockdown finished, I was thinking to myself, okay, what now? I can’t wait for the end of the pandemic because they could all die, and I don’t want to go in their homes and infect them. So I developed a strategy: before each of the interviews, I would spend five days at home alone, just to be completely sure that I wasn’t infected, and then I would go to their place. And that’s also why I only shot sound, because even though my initial idea was to do it like this – only with voiceovers – I thought, okay, maybe it would be good to film just for the sake of recording, to have it. You never know if you might use it. But then I realized that I don’t want to bring a whole film crew into their homes.

It’s interesting what old age does to your body. They’re all in very different kinds of different states, with different abilities. Some of them walk. Some of them are in a wheelchair. Some of them can drive a car. But they’re all deaf. It’s amazing. Maybe one woman out of the elderly people I interviewed could hear normally. When you try to interview them, they’re mostly reading from your lips. So I had to take off my mask too. But they were all extremely happy that I did it and that there was somebody who wanted to listen to those stories. For me, the easiest thing is to work with old people. They’re all very happy that you take an interest in their life stories. And they’re all always at the same place. You can count on finding them where you need them. And, for me, they’re all very interesting. So this is my third project with old people. And yeah, I’m very happy with it.

Did you have so many interviews you had to cut some out or did you use everybody?

I had 28 interviews and I used eight in the end, with one woman who just says one thing. I have maybe 12 or 13 very good ones. I had an interview with a woman who was 102. Although she was still okay mentally, she couldn’t speak very well. Her sentences weren’t very fluid. It was a bit scattered. But it was extremely interesting to talk to her. And I also found her on one of those pictures.

So what was your guiding principle in choosing, first of all, the protagonists and, second of all, the content? How did you manage to cut it down to such an extent?

For the first year and a half I was mostly just reading all the materials that exist on the subject, and there are lots of documents. Lots of the things that they were making over there have been preserved in different museums in Croatia. And then there’s all the newspapers that they were making. There were daily newspapers, but they also had some weekly ones. They had four or five or six different newspapers they were printing over there. There was a separate bulletin for the women’s antifascist movement. There was a pioneer bulletin for school kids. It’s really very interesting. My grandfather even wrote some things about health issues. So it took me a lot of time. I didn’t read everything, but I read maybe half of it. And that was a very interesting source of information, because that’s actually the place where I found out about these living newspapers. These were theatrical presentations of news, which we show in the film.

It was something that had started during the Russian Revolution. It was a way to indoctrinate the illiterate. It’s very smart. But it was also used during the Great Depression in the United States. There was actually a government project by Democrats with theater groups who were roaming around the country doing these living newspapers in the States to promote various policies. Unbelievable. So I discovered that that was happening in El Shatt and that the amateur actors who were doing these living newspapers formed the city youth theater of Split in El Shatt. This theater still exists. So I use the actors from the theater now to play the people who founded this theater eighty years ago in El Shatt.

And did you use original texts from them?

No. I was searching around but I couldn’t find any. So the thing that I did is not a recreation in the sense that nobody knows how it looked exactly, because I couldn’t find anyone alive who could tell me. The people I met were 10 or 11 years old at the time, so they weren’t interested in that kind of thing. I did manage to find one transcript of an original text but I didn’t use it because it was so bizarre, so farcical. I thought that if I did it that way it would really look like I was making a parody of it. So I toned it down a lot. It was very ideological, and it was badly acted in a way, because they weren’t professional actors. So I needed to find some kind of a fine line so it wasn’t a parody of the whole thing, but also not to make it seem too professional. I had to say to my actors, “Don’t act too well. You have to be a bit clumsy.” Some people like it, some people don’t. One guy in Croatia attacked me, accusing me of making a parody of the Partisan movement, but that was not my intention.

I didn’t answer your question. So first I read everything. I wrote down the anecdotes that sounded interesting. There are around ten biographical books that people wrote who were there, but no historian ever wrote a book about the subject. Never in Yugoslavia, never in Croatia, and that’s absolutely unbelievable. And so I picked out different anecdotes. My strategy was to try and find people who could retell these anecdotes but from personal experience. So some stuff I found, some I didn’t. And of course, lots of new anecdotes appeared that I didn’t know about. That was my strategy. And, of course, when I was researching the pictures, all the photographs, I knew more or less what kind of subjects I could show with photographs and what subject I couldn’t show. So I was also thinking about that. So I had them talk about things I knew I could represent. But of course, there were some subjects that I couldn’t represent visually so I had to drop them.

The hard task wasn’t choosing what I would take and what I would leave. The biggest problem was that it’s very episodic, so it was difficult to find the order, how to put all of these episodes together so they have some kind of a logical flow. That was something that we spent maybe a year trying to find in the editing room, with lots of different combinations. We had documentary stuff that was filmed now, film material from historical times, photographs, and these fictional scenes, so finding the right order for all of these elements was the biggest challenge. And in the end I was going completely crazy in the editing room. I couldn’t watch anything anymore. But my editor is a very, very precise and patient person, so she saved it. It was the first time it happened to me. I always try to be slow and patient and I’m never satisfied with just the first decent version of the film. But I also never spend so much time to find the perfect one. I usually stop at some version that I’m happy with. But the editor, Jelena Maksimović, is the best editor in the Balkans. I’m one hundred percent sure of that. She’s someone who searches for the perfect combination, and she won’t stop until we get to that point. So I thank her for that.

How about the materials that you shot in El Shatt? At what stage of the creative process did you film there?

It was somewhere in the middle. I had done the interviews and we had started to edit a bit, but the plan was to go there from the beginning. For me, it was very important to go there, just to try to understand and to feel the place. And to show the memorial. There are lots of little things that I put in the film that are maybe not completely understandable to everyone, but they were very important to me. This cemetery is really in the middle of nowhere and there’s no public transport to get there. It’s a two-hour drive from Cairo, but you need to pass through the Suez Canal, and you need special permission for that. And the whole Sinai Peninsula was still a military zone when we were shooting there. So nobody goes there. These guys who are taking care of the cemetery live there. Two of them. So they are there 24/7 in the middle of the desert in a little container. I asked them how often somebody goes there, and they said once a year. So they’re there 365 days, cutting grass and doing maintenance to be ready for this one visit per year. I wanted to show the absurdity of this situation. There are some initiatives to move all the remains and take them back to Croatia, so people can actually go to the cemetery. But this is completely unmanageable.

At the end of the film we show the only monument in Croatia that’s dedicated to this whole episode. It’s on a very small island. Maybe 100 people live there and nobody goes there even for tourist purposes. And why is it there? Because the sculptor who made the monument in Egypt was from that island. And that’s also a very absurd thing. You know, there were 30,000 people there, all of Dalmatia was there. This story is very important for Dalmatian identity, and there’s just this one monument on this small island. And lots of people don’t know that it exists. And what’s also bizarre is that there is a monument and the list of names, as you saw in the film, but there is no explanation as to what it’s about. So people go there and they just see a statue they don’t understand. That’s what I wanted to show in the end.

Is the debate around moving the cemetery widespread?

It’s not a public discussion. Most or all of the stories from Socialist times, especially the positive ones, don’t get mentioned at all in the public space. There was a documentary made by Croatian television in 2007, because back then there was a big exhibition about the refugee camp in the Zagreb Historical Museum. And they show this documentary from time to time in the middle of the night. But it’s a TV documentary, you have a historian explaining stuff. It’s okay ideologically. But apart from that, nobody mentions the story, there’s no public conversation about it. The ambassador in Egypt told me that he’s thinking of proposing to the government that they should move the remains, but this government won’t do anything. I’m quite sure of that.

I’ll give you an example – some five or six years ago, there was a documentary film about Trieste, the town in Italy near the border. During Communist times, Trieste lived off Yugoslav people who went there to buy everything from jeans to records. So the whole economy was more or less based on that. And then after Yugoslavia collapsed, they had to redefine themselves. So an Italian guy made a film about it, it was called “Trieste, Yugoslavia” and Croatian television co-produced it because he needed some archival footage. And then when the time came for Croation television to show it, they changed the title to “Blue Jeans Blues” or something like that, just to avoid putting the word Yugoslavia in their TV schedule. That’s the level of denial in relation to the historical period between 1945 and 1990. So they’re just trying to erase any kind of memory, especially positive one, about that period. And for me, this is a very positive story. The film already had theatrical distribution in Croatia, we wanted to start showing it before the international premiere because I wanted to show it to my protagonists. Seven of them are still alive, so I didn’t want to wait. And we wanted to do it during the summer because lots of cinemas in Dalmatia are open-air cinemas, so they don’t function in the winter. So we decided, okay, we will screen the film this summer regardless of the international premiere, we don’t care. So it’s great that Dok Leipzig took it. We’ve been touring and showing it. We already have 6500 viewers, which is a lot for a documentary in Croatia with alternative cinema distribution – the multiplexes didn’t want us.

How was the reaction in Croatia?

The reaction was great. People were really flooding to see it. Either people are emotionally connected to that story and want to see the film, or they don’t know anything about it and probably don’t want to see it. You know, when you used to have these bands that had a very dedicated fan base – not a huge one, but a dedicated one – and when a new album would come out, everyone would buy it in the first week, then in the second week it would already drop out of the charts. It’s a bit like that, you know, people who were really interested were desperate to see it. And the reactions were really extremely positive from everyone – from the audience and from critics. At the first festival where we showed the film, we got an audience award and a jury award, which doesn’t happen very often. But it was very hard because I was making a film both for the people who were there and know everything and for people who had never heard of the story; for the people in Croatia who are living in these villages and hadn’t been to the cinema for 30 years, as well as for international film festivals.

So what’s next? More old people?

I already finished a short experimental documentary, and started sending it to festivals. It’s another archival film, a found footage film with archival photographs from a police station. It’s based on photographs of crime scenes. It’s half an hour long, 28 minutes, actually, and I’m really curious to see how everyone will react because I haven’t seen anything like it and I can’t connect it to anything. We’ll see. Maybe it’s a good thing, maybe it’s not. And I already started working on my next feature documentary, which will be about the start of the war in Croatia in 1991, about the chief of police in Osijek, the biggest town in Slavonia. He was trying to prevent the war, as a Croatian chief of police, but he was then killed by Croats. And two days after his murder the war started. It’s another story that I think that everyone needs to know in Croatia, but it could also be interesting for international festivals.

The main thing is you think it’s an important story to tell.

It’s the same thing with El Shatt, I mostly made it for local reasons but it’s an important fact to mention that most Europeans don’t know that different nations had refugee camps in Africa during the Second World War. So there was this Croatian camp in Africa. There was a Greek camp in Africa. There were several Polish camps. One was in Iran, one was in South Africa. There was a Greek camp in Syria, in Aleppo. During the Second World War, these countries were very eager to help the refugees from Europe. We should know that. That was my international pitch for the film. To let people know that it was the other way around back then, and maybe we should return this favor now.

Thank you for the interview.

Leave a Comment