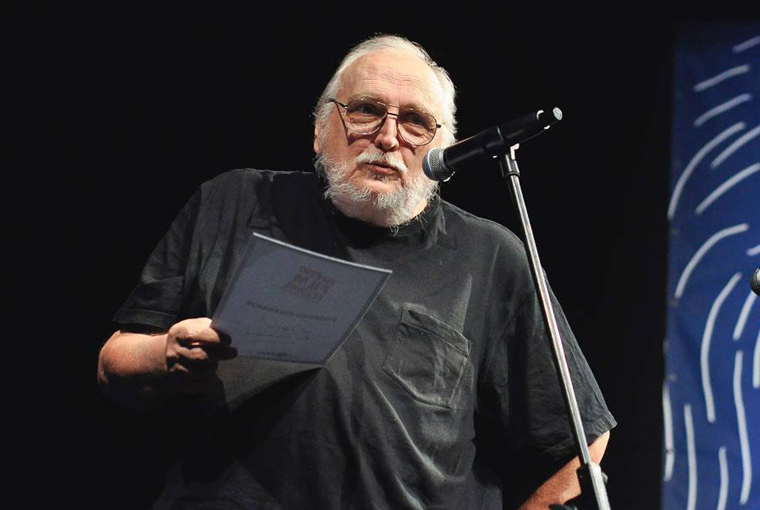

We interviewed Slobodan Šijan, major figure of Yugoslav cinema, who presented his experimental films at AVANT 2022 in Karlstadt, Sweden (September 23-24), an international festival of experimental film. Šijan recounts how he began to make experimental films, what the “kino klub” experience was like, and what he learned from Croatian experimental filmmaker Tomislav Gotovac.

Could you tell us something about how it all began? You started your career painting, at the Art Academy, partly influenced by the ‘Mediala’ art movement, a movement interested in the suppressed parts of civilization, and then you got involved in the New Art Practice. What brought you from that painting background to experimental film?

In the beginning, I was a bit under the influence of the Mediala movement, but later on I moved to something closer to the contemporary New Art Practice, as critics called it at the time, a conceptual art movement that investigated new media, and experimental forms, criticized traditional art forms and that was very prominent in Yugoslavia. During my studies at the Art Academy, I began being interested in cinema and time-based art forms. The classes were very divided at the time, there were no film classes that you could take at the art academy. So, I saw in the papers that a film school was opening, where a great director will be taking a class of students. His name was Živojin “Žika” Pavlović, a major director of the Black Wave. I applied, hoping that I can learn something. It was very hard to get in but I did. I was lucky, as I was a graduate of painting. And Pavlović was a great teacher, he caused rebellion amongst professors because of his methods. He wouldn’t grade his students, telling them they would get the highest grade if only they handed in their film. “If you don’t bring the film no matter what you fail. You cannot complain about the school not giving you the camera, I am not interested.” He was very brutal. A lot of people didn’t pass the class because they didn’t bring their film. Nobody complained, I somehow survived. But after two years he was thrown out of the school because of the political climate at the film academy at the time. His films were of high quality, they entered big festivals, but were very critical politically speaking.

They also kicked out another director who won a prize in Cannes: Aleksandar Petrović, well-known for his film I Even Met Happy Gypsies. They tried to make him quit, so they degraded his status, he became part of the school staff – supervising and cleaning, erasing the chalk from the boards, helping with the equipment – but he didn’t want to quit the academy. He told me: “They gave me a job where I can sit and write my novels. I don’t want to leave”. Later on, the political climate calmed down. Someone from the directors’ department wanted to bring Pavlović back. He said to one of our colleagues, “that idiot wants to bring me back, please don’t let him do it.” And then he started to teach again. He was an interesting guy.

We had a lot of freedom, but it only lasted for two years. After that there was a big scandal, with Lazar Stojanović’s film Plastic Jesus, which was too radical and critical of Tito’s regime. Official committees began examining the professors’ work, as well as our student films – in our presence though. Those were turbulent times.

Could you tell us more about cultural life in Serbia in those days?

In Yugoslavia, free and calm periods of time came from time to time, but they didn’t last too long. Between ’68 and ’72, there was a lot of freedom in the arts, in cinema, and really good films were being made. And then there would be some turmoil, and hard policies would suddenly be introduced. In 1972, Tito made a speech attacking contemporary art, which was followed by cuts that targeted cinema in particular. The scandal of Plastic Jesus was due to it criticizing Tito himself, which was an absolute ‘no-no’. Before films were criticized because they showed the negative side of socialism. But they didn’t attack the leader himself. This film was brutally making fun of Tito (with found-footage images of Tito, nudity in the streets). From that moment on, they started removing suspicious filmmakers from the academy. Many left the country and went on to become international directors. We were left without a professor in the school, as they kept replacing teachers. The fourth year of studies, I did my military service, so I just left the school – they were glad not to see us at the film academy anymore. And then I did some work for TV. It took me seven years until I made my first feature film.

How about your experimental filmmaking that you presented here at AVANT 2022, how did it relate to your later feature projects?

I made experimental films during my time as a student, but not for school. I used the equipment from the school, the 16 mm camera. I made a film with Paul Pignon, a well-known British experimental film musician, who lived in Yugoslavia and now lives in Sweden, based on his tape music. I found ways of doing things that were not obligatory for the school because for school you had to do some narrative pieces. And then I started to work for TV, with dramatic features. I made five TV movies, based on scripts with actors. I like them, they are regular narrative stuff. The scripts were successful. I made four features in five years, which is rare. After that it all became difficult in Yugoslavia, everything was falling to pieces. So I moved to the US.

What were the films at the time like?

There was a very bad atmosphere for four years with terrible filmmakers after 1972. The films being made were state-sponsored projects, which were very ideological, say portraying our fight against Nazis during WWII. People from our film school were like black sheep, so we couldn’t get work. Other filmmakers who studied abroad (who were not part of the group around Plastic Jesus) succeeded. I found a way to move on along with them.

Could you talk more about experimental cinema, and can you tell us about the kino klub experience in Yugoslavia, that is the influential network of amateur filmmaking clubs?

My experimental films gained some new attention in recent years. Screenings for galleries and museums have been organized. The experimental cinema tradition was very strong in Yugoslavia, but it was linked to the kino klub experience. But I belonged to the generation that was not actually making films inside the kino klubs, like Tomislav Gotovac, the Croatian filmmaker who inspired me. In the 70s, we moved outside of kino klubs, because kino klubs became a bit old-fashioned. They were gradually being professionalized: you had to submit a script and then a committee would decide what is good or bad. It was all very boring, and time-consuming. So, we found some cameras, and did films for ourselves. But some of us never applied to festivals.

The curators were interested in what we did. For instance, with my fanzine ‘Film Leaflet’, curators began being interested in the context of the New Art Practices taking place in the student cultural center in Belgrade, where Marina Abramović and major artists of that kind of art started their careers. The New Art Practice artists used different techniques for their art – so if I needed a silk screen (for my ‘Film Leaflet’ for example) I could get it there. If cinema was destroyed by the political climate, New Art Practice forms of art were left in peace. It was an important scene.

If we look at these films – what are some of their themes?

Psychedelic art had a strong influence on me in this period, especially on Self-portrait at the Cemetery (1970) and Kosta Bunuševac in a Film About Himself, (1970) about this psychedelic artist in Belgrade. Then my films were dealing more with the structure of visual material. My films then became closer to the ‘art informel’ movement in painting, but done with film. I liked experimenting in different directions.

For example, I made a flicker movie which was interesting, as it wasn’t produced in a classical flicker style. In The Garden of Forking Paths, which is the title of a Borges story, I shot mountains burning on an island in the Adriatic on double 8 mm footage but exposed it on a 16 mm camera. This yielded a 16 mm film that was perforated twice as frequently and exposed on one side and then exposed on the other side, after flipping the film roll inside an 8 mm camera – it was then split down the middle after development, to produce an 8 mm film. What I did is that I shot the double 8 mm film on a 16 mm camera and then shot half of it in double exposure on an 8 mm camera. I then sent it to be developed and cut in half, so it was ultimately screened as an 8 mm film. The flicker effect then comes out from the 16 mm frame being split and exposed in parts, with the exposure varying according to the region of the frame.

Looking back at the beginning of my career, my work is very diverse, but with my experimental films I was mostly interested in textures and structures. But I also had an interest in garbage and extreme situations – I made films on junkies, graveyards, or dumps.

Regarding sound, how do you work?

I like using existing pieces and I am interested in structures. I used what I like – which is experimental music, pop rock. I used Spanish gypsy music for my film on dumps. I don’t know what the words say, maybe the singer is singing about a beach, the background sound for images of a dump! During socialism we listened to rock music and commercial music for TV, and blues music – which I used for my films. If the film was more abstract, a piece of electronic avant-garde music would be suitable, like Xenakis music or Paul Pignon, who was important in Yugoslavia at the time. In Morning in Pink, we destroyed the sound using our mouths on the microphone.

How about Tomislav Gotovac, the great Croatian experimental filmmaker whose work was also shown at AVANT 2022, what did he teach you?

Tom was a major author, he started out in 1963 in Zagreb and then moved to Belgrade to the Film Academy in his thirties in 1967. He had some financing and made three films that were so-called proto-structuralist films, using minimal forms of expression, resorting to the fixation of camera movement, concentrating on the direction of film-movement. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of cinema from Howard Hawks all the way to experimental cinema. He was also a performer, and sometimes a sexually provocative one, performing naked.

Tomislav was my hero because he taught me the important notion that cinema shouldn’t just consist of hermetic authors making experimental films but that all movies had a value. That is why I like features, comedies, and experimental film, and I make no discrimination between art or commercial ‘trash’. The term “anti-film” that was used to talk about his films was a concept that was invented at the time by critics of the New Art Practice, but really we both had a great fascination for all kinds of cinema, including Hollywood.

Could you tell us what you are working on at the moment?

Currently, I am shooting a comedy feature film. We are on the verge of finishing it – we have ten days of shooting left. It is about a 1930s avant-garde artist in Belgrade.

Thank You for the interview.

Leave a Comment