From Formlessness to Structures

Slobodan Šijan’s Experimental Films

Vol. 131 (January 2023) by Anna Doyle

The 2022 edition of AVANT, Sweden’s only film festival solely dedicated to experimental cinema, took place in Karlstad and Kristinehamn in September, after two years of shutdown because of the pandemic. The festival, which launched its first edition back in 2002, showcases a program of historical films curated around a chosen theme. Swedish experimental film researcher John Sundholm is responsible for the rigorous programming at this festival. Baltic experimental cinema and comedy in experimental cinema were two of the themes of recent editions. This time, inviting Serbian curators Aleksandra Sekulić and Dejan Sretenović to collaborate, the curator wanted to delve into an important epoch of experimental cinema: the 60s and 70s in Yugoslavia. A period of emancipation for experimental cinema in the US (structural cinema and underground cinema emerged at the time), the period was also a key epoch for experimental art in Yugoslavia, with the emergence of what critics of the time called the New Art Practice movement. Based around Student Centers and kino klubs across Yugoslavia and thus outside of the traditional educational system, the New Art Practice was an anti-conformist way of making art. It was collaborative experiments rather than polished works that were here extolled, with different mediums being used in democratic ways, from performance to printmaking to cinema, usually in an effort to challenge the conventional social praxis at work in Yugoslav society. The two main artists of the program at AVANT were involved in this movement, although both developed their trademark signature outside of it: filmmaker Slobodan Šijan, guest of honor at the festival, and performance artist and experimental filmmaker Tomislav Gotovac, who was a great influence on Šijan.

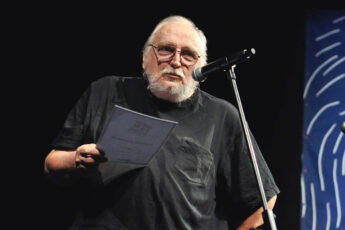

With his baseball cap adorned with the words “BIRTH/FILMS/DEATH”, Šijan presented his films in an old 70s brutalist building in Karlstad as well as in Swedish experimental filmmaker Gunvor Nelson’s home city of Kristinehamn. In Kristinehamn, visitors got to see Šijan’s ‘Film Leaflet’, a fanzine he created in the late 70s. Best known for his cult comedy Who Is Singing Over There? – a well-acclaimed film that supposedly inspired Emir Kusturica’s style – at AVANT, we saw a different facet of the comedy master. Šijan’s experimental films were made during the course of two years of great freedom in the film industry in Yugoslavia (1970-1972). They were produced as side projects to the curriculum at his film school in collaboration with some of the filmmakers of the Black Wave, outside of the kino klubs and their regulatory practices, and right before Šijan started writing for television. They were also made before purges in film school began to happen, when Tito started condemning contemporary cinema after the scandal of the anarchic collage film Plastic Jesus (1971) by Lazar Stojanović. In this polemical collage-film, Stojanović openly criticized the cult around Tito’s personality. Stojanović’s film was the pinnacle of formal and political provocation, willingly creating disruption in a society whose supposed Communist ideals did not reflect what the new generation was actually experiencing in their everyday lives. After Šijan graduated from painting, he became interested in an art movement called Mediala, then studied with filmmaker Živojin Pavlović, one of the founders of the Black Wave cinema movement. Šijan began to be interested in DIY experimental film right around the time when the New Art Practice emerged. Although this movement was known for producing a strand of ‘anti-film’, conceptual films that refused the status of art and subverted the usual characteristics of conventional films, instead involving the spectator in the process, Šijan’s work belies a fascination for cinema both as art and as entertainment.

This is evident in the ‘Film Leaflets’ that Šijan made between June 1976 and December 1979. The work of a cinephile, the ‘Film Leaflets’ were printed DIY fanzines that were distributed in front of the Pula film school in the late 1970s. In total, 43 film leaflets were made, drawing inspiration from such wide-ranging sources as Yugoslav anti-films, Hollywood trash, and Italian auteur cinema. Born out of the exasperation of saying anything about film, the leaflet took the shape of diary-like notes, texts and lists, collages, photographs and xerox prints, following Šijan’s definition of a film leaflet: “halfway between poor graphic and samizdat, created with the idea to make once a month visual and textual statement about film or related to film.”1

In the leaflets, the history of cinema is examined in its different facets. On the wall of the center in Kristinehamn, the leaflets are all aligned: we see the journalistic document of the death of Elvis Presley with a quote by Presley on how he despised Stanislavski’s acting techniques – below that we see a photo of non-professional actors appearing in Šijan’s film. Film lists as well as storyboards for imaginary films mingle together next to a very graphic John Wayne cigarette ad, as if to say: there should be no hierarchy between trash and art film. Auteur cinema is reinterpreted as Šijan adds Croatian experimental pioneer Tomislav Gotovac to famous experimental film critic Paul Adams Sitney’s list of structuralist experimental filmmakers taken from his monumental book Visionary Cinema. Incidentally, Gotovac’s films were also shown at AVANT. Labelled somewhat misleadingly as a ‘proto-structuralist’ filmmaker, Gotovac was using specific structural rhythms as a form to organize the non-narrative of his films. He adopted this technique before structural cinema was even theorized by Paul Adams Sitney in the 1970s in New York. The Croatian artist was also a pioneer of performance art. And, in the legacy of the early avant-garde his main idea was that cinema was an experiment with life itself rather than a representation of it, blurring the borders between mimesis and physical presence. Activating film spectatorship and criticism of film by “other means” through his leaflets, Šijan addresses the impossibility of discriminating between high art and low art, between DIY, Howard Hawks or Vincente Minelli, and therefore acknowledges the impossibility of film as evaluative criticism.

Following the showcase of the leaflets in Kristinehamn, Slobodan Šijan’s experimental films from the short period from 1970 to 1972 were the object of a retrospective in Karlstad. Trash culture is not Šijan’s only interest on the fringes of our civilization, but also trash itself. Drawing on his interest in textures, materials and structures, the film Šijan made at the Belgrade dump entitled “Garbage Dump on ada huja in Belgrade” (1970) defies good taste. Accompanied by a Spanish tune of Romani music to create an ironic contrast between civilization and non-civilization, the junkyard appears to us in a new form and almost strikes us as beautiful. Inspired by art informel, Šijan in a way applies its principles to cinema – the film depicts the materiality of waste, lending a raw expression to cinematic gestures. Art informel was a painting movement that combined rough expressionist painting and an interest in formlessness – take Jean Dubuffet’s paintings or the work of Italian artist Alberto Burri, who himself used burned wood, jute bags and sheet metal to make his paintings. In retrospect, Šijan’s film seems to fit French thinker George Bataille’s definition of ‘l’informe’ – he creates form in formlessness so as to “affirm that the universe resembles nothing and is only formless amounts to saying that the universe is something like a spider or spit.”2

In the same vein, the short film Fixanje (1972) fixates the camera to picture a sweet outdoor scenery of children playing in front of a house, before it delves into what is hidden behind the walls of the house. A man, whose charismatic acting could have been taken out of a Spaghetti Western or a Douglas Sirk movie, is seen consuming drugs in the half-abandoned house. Šijan tells us it was the most famous junkie of Belgrade who died young. The film’s fascination for the marginal figure of the drug addict foreshadows the punk film movement of the 80s. A decade later, in the punk atmosphere of New York City, famous experimental film artist David Wojnarowicz’s super-8 film Heroin (1981) portrays a junky travelling New York City, finally reaching an abandoned zone of the city where he injects heroin into his body.

Another of Šijan’s interest is cemeteries, not so much by way of paying homage to the dead but so as to subvert the sacred. In his Self-portrait at a Cemetery, the superimposition of Šijan’s face with the background of a cemetery creates a psychedelic connection between the artist and his fascination for death. The 1970 kaleidoscopic portrait of a painter, Kosta Bunuševac in a Film About Himself, also depicts the multicolored experiment that psychedelic art entails – here painter Kosta Bunuševac engages with life through his materials and colorful studio environment. In Morning in Pink – the color referring to Edith Piaf’s famous song ‘La Vie en rose’ – the film depicts the adventures encountered by the technical film crew who are filming and recording sound at the cemetery, exposing the production process of the film. The crew meet the local people wandering around at the cemetery, who scrutinize what the crew is doing there. Here the fourth wall is broken to subvert the idea of the cemetery as a subject of melancholy and place of desolation. Ironically, it appears as a place of everyday interaction instead.

Following up on this fascination with death through irony, Corpse (1971) is an experimentation with both animal documentary filmmaking and with the limits of observation. Provocatively, the camera openly documents the slaughter and skinning of a pig. This ethno-cinematographic ceremony creates disgust and makes the viewer conscious of human cruelty. When an insert of a female body in the window appears, another ironic contrast is created with the editing so as to desacralize the film subject. Coincidentally, this film was made the same year as Jean Eustache’s documentary Le Cochon, which adopts a similar structure, subject and subtext: the film also deals with the slaughter and skinning of a pig on a farm. Both films are playful engagements with observation and with the hidden aspects of animality but of course with those of humanity as well.

The use of sound in Šijan’s films is nothing short of thought-provoking. From one film to the other, we hear Spanish Romani music, American pop songs, psychedelic rock, or more experimental sound creations that often resemble noise. In his homage to Kubrick entitled “Yeah”, English experimental composer Paul Pignon’s soundtrack is accompanied by mouth and respiratory noises that have been distorted by the microphone. In the strange and stressful ambiance of what appears to be a film within a film, we follow a half-bald man’s adventure through offices and corridors in which he is stuck, to his finding a way out into the forest. Then the camera settles on structures and textures: on walls, grass, trees and clay. The slithering labyrinth of the non-narrative creates an almost hallucinatory feeling as new anonymous characters are inserted and the image turns blurry.

Slobodan Šijan’s experimental cinema is an experiment that lends structure to what is normally without structure, form to what is formless. Inheriting the idea of Tomislav Gotovac that there should be no hierarchy between art and life, experiment and form, high art and low art, the waste and trash of humanity is raised to the standards of beauty. Though he depicts marginal textures that are unwanted, visions that are impossible to see or tolerate for the human eye, he does so with an unwavering fascination with beauty and structure. Through these means, Šijan’s fascination with multiple forms, textures, and structures of the repressed and dark sides of society sheds light on a more abstract vision of what the Black Wave of cinema was already trying to point out with its anarchistic fictions and dark comedies about the comedic despair of life in socialist Yugoslavia. Experiment and life are intertwined through the medium of cinema, and the ironic gap between the two emphasizes a raw understanding of our humanity. After Tito’s intervention and the ensuing witch-hunt in the cinema industry in the 1970s, student films began to be controlled by a committee. The political climate in which Šijan made his experimental films thus vanished.

At AVANT, Slobodan Šijan was warmly welcomed and his films were discussed with passion, especially as Tomislav Gotovac’s influence on him was brought to light. Šijan’s film A Poem for Tom movingly captures some of the last moments he spent with Gotovac before Gotovac’s death, for whom cinema almost surpassed life, and whose radical influence on experimental art and performance in the 70s on filmmakers from Marina Abramović through Slobodan Šijan to Neša Paripović was singular.

References

- 1.Šijan, Slobodan (2009). Filmski letak 1976-1979 (i komentari) / Film Leaflet(s): 1976-1979 (with comments), Beograd, 9.

- 2.Bataille, Georges (1929). Informe. In: Documents 7, December 1929, 382.

Leave a Comment