We met Armenian director Harutyun Khachatryan during the L’Europe autour de l’Europe festival in Paris. We spoke with him about his last film “Endless Escape, Eternal Return”, some of his older works, and the theme of return in his films.

Did you know from the beginning that you would shoot “Endless Escape, Eternal Return” over decades?

I didn’t plan anything. I just have a feeling when something is finished. I started filming the movie twenty-five years ago and in the middle of making it, I realized that it was incomplete. So we just continued. Then later, we learned that it really takes a long time to understand what is happening, also to understand oneself. So twenty-five years was a good time for that as well.

What was your motivation behind making a portrait of artists?

There were a lot of people that I met, six of whom were very interesting. Out of those, only four remained, mostly artists: a painter, a theater director, and a musician. The fourth one was a driver. They emanated a very special energy. They all had their problems, tensions, and joys. It was interesting to follow them. It also depended on how they would open a conversation with me. Since the conversations were very sincere, it was essential that they could tell things. The driver was the most open and accessible person.

Watching the movie one doesn’t have the feeling that so much time passes. The aesthetics are very homogeneous throughout the film. How did you manage to make the images look alike?

I think it depends a lot on my own aesthetics. If I don’t change, the looks of my films will not change either. While editing, however, I would notice that there were slight differences in the film which I then tried to level. Maybe it’s also connected to the fact that when I started the movie I was already mature, not only as a person but also as a filmmaker and artist. I was 32 when I started filming it. As I come to discover now, the secrets of the movies I try to make, is that they don’t age with time. Of course, I try to recreate the atmosphere of the specific time I am filming. As soon as there is one little false note, you will notice it.

At the end of the film, the main character says that he wants to die at home, in Armenia. What significance do you attach to your subjects’ relationship with their home? What does it mean to come home?

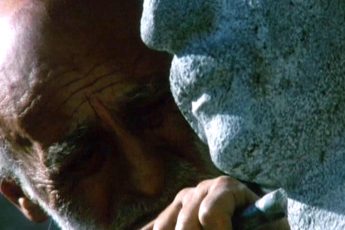

Armenians are very closely tied to their roots. A lot of my movies have the word “return” in their title. Every year, I return to my hometown, and I ask myself if there will be someone waiting for me the next year. In Return of the Poet, there is another Armenian character who was away from his homeland and longed to return but couldn’t. So in the film, I take a sculpture of the poet back to his hometown. But will there be someone waiting for him?

Does “home” signify something personal or is it an ideal, for instance a solidary feeling shared by an entire people for their language and cultural heritage?

A lot of Armenians have been living in exile for a very long time. So this theme of returning is very painful. Armenians live in different places and they had to take their country with them wherever they went. So yes, this connection is very vast and affects different people from Australia to the USA. But it is also very personal.

What is the conflict between this nostalgia, the hopes and ideas people attach to their home and the reality at home?

We say that you can always recognize an Armenian by his eyes. There is a deep sadness in his eyes. Of course, the identity Armenians create abroad does not necessarily match the identity they find at home. If you look at Armenian cemeteries abroad, you realize that they don’t resemble cemeteries in Armenia.

Some of your films, like “Border” or “White Town”, are more explicitly political in treating national and ethnic conflicts. Is there something like an Armenian or Caucasian identity?

I am not a friend of borders. In fact, I hate all the limits that people try to impose on themselves and on other people. Certainly there is something like an Armenian identity, but the question is whether that is a good thing. I have another very dark movie, The Documentalist, in which things are being said about Armenia that are not at all positive. But this is part of the times we live in. Take cinema politics. It is catastrophic how Armenia is still unable to communicate with Russians, Turks, Azerbaijanis… Nobody is really giving such collaborations the right importance.

Today, you are also the director of the Golden Apricot Film Festival. How is Armenian cinema developing?

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, it seemed liked everything was over. You couldn’t produce movies anymore, there was neither money nor infrastructure. But there were two ways to recreate a cinematic culture, through foreign co-productions or through a festival that would teach people to love cinema again. So we chose the second path. When we started, there were only six or seven films screening and today there are more than twenty.

Are there any current trends one should be aware of?

Well, in the past there was something like a common aesthetic or shared vision. Today, every film is very different, so I can’t yet see what the face of Armenian cinema looks like. Maybe in a couple of years there will be directors with their own poetry and vision. It needs some time.

Thank you for the interview.

Translated by Ivanka Polchenko

Leave a Comment