A Statue for Nostalgia

Harutyun Khachatryan’s Return of the Poet (Poeti veradardze, 2005)

Vol. 52 (April 2015) by Moritz Pfeifer

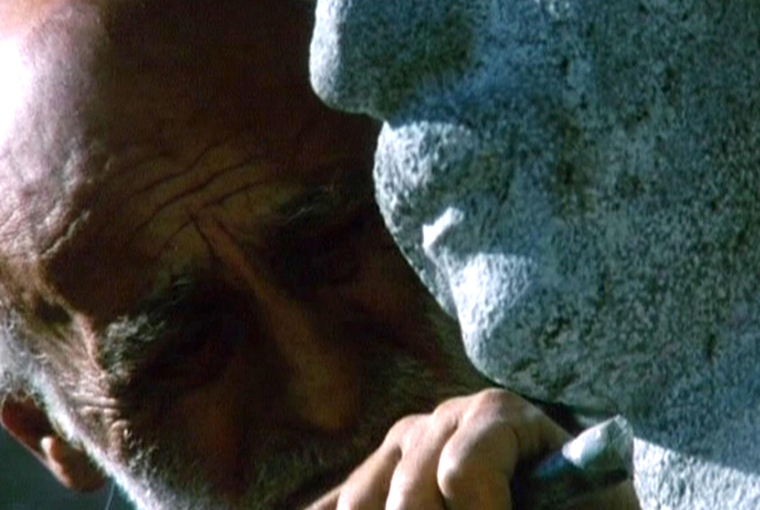

The main actor in Armenian director Harutyun Khachatryan’s 2005 Return of the Poet is a stone sculpture of Ashugh Jivani, a late Romantic folk singer who lived at the turn of the last century. Khachatryan’s documentary avoids conventionally biographical storytelling and focuses entirely on the artistic creation of the larger-than-life size statue in Yerevan and its journey home to Kartsakh, Georgia. Traveling on a multi-axle truck bed, the statue visits Armenian sites and traditions: folk festivities, century-old churches, peasants, and what looks like a country in ruins. By constantly alternating between images of the statue on the truck and of the Armenian landscape and people, the film slowly insinuates that everything outside the truck is part of the poet’s vision. And so the film establishes a historical connection to the life of the real Jivani who was known for traveling the Caucasus as a wandering troubadour, singing to strangers about the mysteries of his homeland.

Return of the Poet is a truly impressive achievement of nostalgic contemplation. First there is the poet’s homecoming, which obviously describes a sense of longing (algia) for a home (nostos). Home, however, can mean many things in this film: it could describe the poet’s love for his origins, his personal roots in Kartsakh where, after a century of displacement, Communist occupation, and national and ethnic discord, he is finally allowed to peacefully return. Symbolically at least. But home could also represent his social roots, the entire Caucasus as a region where national, religious and ethnic differences do not matter. Jivani himself embraced this vision of solidary and brotherly Transcaucasianism. In one of his songs, he writes of the transience of national movements:

Earth to her well-taught son belongs, with motherly caress,

But the unlettered races like nomads come and go.

Jivan, a guest-room is the world, the nations are the guests;

Such is the law of nature; they pass—they come and go.1

Jivani died half a decade before the Armenian Genocide of 1915. He grew up witnessing the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the national awakening of the 1880s and 1890s. Through his songs, Jivani protested against foreign rule but was as skeptic about the national movements that started during that period. Many of his works lament over the tragedy that people’s love for their homeland corrupted them to hate foreigners. A century later, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and Armenia reliving similar resurgences of national and ethnic conflict, Jivani’s “return” also signifies the re-occurrence of a historical cycle.

Nostalgia is also temporal. The sculpture of the poet, the songs, and architectural edifices in the film may represent a longing for a more peaceful artistic and cultural period. Do the peasants and villagers return the poet’s gaze? On various occasions singing peasants interrupt the film’s narrative, seemingly replying to the poet’s advent. Tradition survived and is, if not in full bloom, at least returning. Clearly then, Khachatryan’s longings for the past are also determined by needs for the present. His nostalgia is not only retrospective but also prospective.

Khachatryan – Return of the Poet

This prospective nostalgia makes the film differ from earlier Armenian representations of nostalgia, in particular from Sergei Parajanov’s 1968 The Color of the Pomegranates (Sayat Nova), a highly symbolic biopic about another 18th century Armenian troubadour. The music as well as many images in Return of the Poet such as the Armenian churches, a ritual lamb slaughtering, donkeys, horses, and even Khachatryan’s frontal staging (most notably in the scenes of the singing peasants, see image above) reflect the poetic imagination in Parajanov’s master piece. However, even though Khachatryan’s images are symbolically charged, they are never as stylized or dreamlike as in Parajanov’s film. The reason for that may be that Parajanov’s poetic visions are no longer out of reach. For Parajanov nostalgia had to remain an individual endeavor, an inner refuge; for Khachatryan it has become a historical reality. His dancing and chanting peasants are real. His poet is wrought into enduring stone instead of flickering as a fragile shadow on a screen.

Nevertheless, there are tensions between the past and the present in the film, which are most evident in the constant juxtaposition of images depicting either creation or destruction. Shortly before visiting the studio where the statue is being built, a mountain top is blown up whose debris will presumably bestow the material for the statue. During the journey, the statue witnesses other cultural restorations. In one scene, a traditional Armenian church gets decorated with a new dome and reconstruction sites start appearing among the innumerable ruins of churches and stone edifices whose purpose is no longer quite distinguishable. Although Khachatryan’s film does well in overlooking aspects of the country that are explicitly reminiscent of Soviet rule, his film makes it obvious what parts of traditional social life have been left to neglect – religion, community life, and art. Similar to the explosion of the mountain, their destruction now inspires renewed cultural and artistic developments.

Ironically, it was Karl Marx who came up with the idea of creative destruction. Marx used it to describe economic processes in which the destruction of productive forces, through crises and wars, becomes necessary to keep the general productivity levels going. The concept of creative destruction seems to apply quite well to various aspects of life following the collapse of the Soviet Union. One could mention, for example, the voluntary (and pleasurable) destruction of Soviet monuments – a more nostalgic rendering of the destruction of an oversized Lenin statue can be seen in Theodoros Angelopoulos’ Ulysses’ Gaze (1997) – or the rapid replacement of Soviet architecture in Eastern Europe’s metropolitan areas by high-tech commercial centers and business zones. Regarding creative reconstruction, one might mention the astonishing revival of Christian culture and nationalism in the former Eastern Block. In Khachatryan’s film, the construction of the statue breaks with the Soviet taboo on any form of national reminiscence and represents the reestablishment of cultural roots and national heritage. But this creative destruction appears to happen quite naturally, in a more melancholic and rehabilitative manner than is suggested by, say, the construction of a 33-meter Jesus statue in Świebodzin, Poland in 2011. Khachatryan’s view on Armenia’s cultural revival seems to lack the frenzy with which oppressed customs sometimes return once they are liberated. Most importantly, he leaves room for sadness which other cultural reawakenings are quick to ignore.

Nostalgia used to be considered a sickness and some, perhaps justifiably, still consider it a potentially dangerous catalyst for national pride and historical whitewashing. A statue glorifying Jivani may appeal to the pride of an Armenian nationalist as much as a bust of Lenin once enticed Soviet apparatchiks. At times, Khachatryan’s movie seems to suggest that the poet’s statue, unlike a bust of Lenin for instance, is truly eternal. But this should not be confused with nationalism. Like in Jivani’s poem, “nations” are only guests on earth, whereas beauty, spiritual inspiration, and communal values convey a true sense of belonging.

Antoine Agoudjian – Rêve fragile, Armenia, 2004

Khachatyan is not alone in having nostalgia for these eternal or timeless customs and ideals. Photographers like Antoine Agoudjian and Josef Koudelka have recently portrayed Armenia in a similar light. Their photographs strikingly resemble the poetic visions in Return of the Poet with churches, ruins, landscape, religion, and community being popular motives. The early Christian ritual “Pehlivan” portrayed in Agoudjian’s picture (above) conveys a similar restorative meaning like the feasts depicted in Return of the Poet. It simultaneously points at the rich traditional customs of the Armenian people and celebrates their contemporary renaissance.

Joseph Koudelka – Untitled Armenian Series, 2006

Koudelka, however, seems more skeptical about the reality of this nostalgic vision. In an untitled series on Armenia from 2006, he juxtaposes the old and the new more violently. One picture depicts the remnants of an ancient edifice in front of an amusement park and several social housing blocks. The image above compares a border pole with a Christian cross, suggesting that religion causes as much discord as national borders. Such a view contradicts Khachatryan’s and Agoudjian’s harmonious representations of Armenian religious customs, which unite more than they divide. Generally, their images of “home” are unbroken, and conflicting analogies between the past and the present are absent from their work.

And yet, they don’t hide the fact that there is a good dose of wishful thinking in their depictions of the present. After all, the nostalgic “visions” in Khachatryan’s documentary are those of a dead poet and the dreamlike quality of Agoudjian’s should also not be ignored. Perhaps, then, the longing for such an unbroken home shows their vulnerability more than anything else. Their nostalgia is true because it can never be restored. It describes the paradoxical effort of replacing the stolen time of the past with the present. But monuments of poets, be they as perennial as mountains, can at best symbolically make up for this loss. Everything else is called mourning.

Leave a Comment