A Poem of Decay and Freedom

Maria Saakyan’s I’m Going to Change My Name (Alaverdi, 2013)

Vol. 97 (September 2019) by Antonis Lagarias

Maria Saakyan’s I’m Going to Change My Name is one of those carefully structured films that use the opening sequence to reveal both the main themes of the story and the cinematic tools that will be used to tell this story. The opening titles, letters appearing on the screen to the sounds of a typewriter, are interrupted by different shots of a scene that will not reoccur as the film progresses: a hot-air balloon, propelled into the sky by a fire-spitting machine, is chased on the ground by a small girl calling out for her mom. This sequence anticipates how the film will deal with the absence of parental figures, and that it will mostly be crafted by dream-like sequences. Instead of a linear story structure, scenes and events will be repeated over and over with sense-manipulating sounds playing in the background, suggesting that information will be passed to the audience in an indirect, fragmented way.

The story of the film is common enough. Set in a small village in Armenia, it is the coming-of-age tale of teenage girl Evridika (Arina Adju), who has never known her father and lives with her oft-absent mother. As Evridika tries to establish an identity for herself, independently from her mother (as suggested by the title), she spends her time exploring the village together with her imagination, spends time discussing suicide on chat rooms, and sees her sexuality come into bloom. Her sexual fantasies are directed towards Kiku, a chatroom member with whom she imagines having an erotic scene. At the same time she meets Petr, a man who speaks to her with lines from the Rilke poem ‘Orpheus, Eurydice, Hermes’, and who will later be revealed to be both Kiku and her father. As Petr does not know Evridika is his daughter, he will try to sleep with her, an endeavor which will inevitably culminate in tragedy.

The process of growing up and shaping one’s identity is the main philosophical concept to affect the way the film is shot. As Evridika realizes that she has to develop her independent subjectivity, she also needs to assume certain things and reject others. It is a process that the film approaches both thematically and technically. Thematically speaking, this process of identifying yourself through your relation to others is visible in the fact that Evridika’s mother is absent from the beginning (save for the opening sequence), while the rest of the film depicts a form of patricide. At the end of the film we are left with a young girl who has no emotional ties with either of her two parents, a state that can be considered as ‘freedom’ and that allows her to choose ‘her own name’. Other social determinants, like religion and the patriarchate, are only hinted at in the film. This suggests that the director sees family, and especially parents, as the main factor to determinate people’s identities, eventually demanding acceptance or rejection.

Evridika experiments with different ways of seeing reality, of documenting events and herself. The scenes are interrupted by shots of stop motion animations, a drawn donkey who comes to life, subjective close shots or shots of her computer screen. She takes many pictures of different parts of her body (shots of her mouth or her eyes, for example), thus creating her identity by consciously creating images that represent herself. Also, she is constantly filmed looking through closed windows (sometimes even cracked one), and time and again the filmmaker approaches Evridika through her reflection. Both filmmaking angles reflect the indirect way Evridika herself observes reality.

If it is fair to say that thematically the film is not too innovative, its strengths lie in the playfulness of the filmic technics used, and the fitting editing style: the fragmented way that the story is being told, the rich variety of different visual and aural elements, and the strong sense of subjectivity conveyed, all channel the viewer’s attention towards Evridika’s personal struggle. The film looks like an elliptic collage, championing a coexistence of different elements which are all part of a poetic coherence that brings to mind the way Tarkovsky describes the fragmentary and nonlinear way that people recall their memories. The reference to Rilke’s poem and the reading out of different parts of Evridika’s own poems in the off, are all part of an overarching effort to transform the film into a poetic tale. While Saakyan’s stylistic approach may seem intellectual or forced, the film is better understood as experimenting with both the deconstruction of narration and with breaks in continuity. Perhaps the best example of this is the ‘rain scene’ in the middle of the film. Evridika walks in the house in her underwear and is seen searching for her mother, who has disappeared from the house. When we return to the scene following a short flashback, the sun is shining bright while Evridika still wears the same clothes, recreating the exact same scene we saw before. Like the opening sequence, in which another symbolical scene is repeated over and over, this narrative interlude visually represents the feeling of parental absence. By looping such images in a seemingly endless circle, Saakyan breaks up the space-time continuum. Meanwhile, the sound is often unrealistic and repetitive, overshadowing the visuals with electronic distortion and strong reverb, both of which suggest a subjective use of sound and more specifically, a distortion of reality. The sounds of flying bugs or metal spinning create a sensorial collage of logically ‘impossible’ elements.

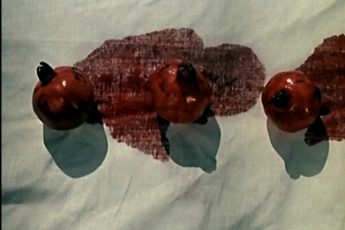

Because there is no distinction between subjective shots of Evridika’s world-view on the one hand, and the concept of an objective reality on the other, the whole film reads like a blurry and dark poem shot entirely through Evridika’s subjective perspective. For instance, all sequences featuring the village seem to be shot from her psychological point of view, portraying smoky skies, faded colors and abandoned industrial buildings. As Petr says to Evridika, her poetry is sad and speaks of death. Everything – even the adults, who also seem to be in a state of depression – are filmed in a way that evokes their impending decay – as Evridika puts it, ‘like an apple I forgot in my bag for two weeks’.

The film’s subjectivity helps us understand its symbolic ending, which has Evridika finally stay on her own and thus fulfills two functions. First, it represents Evridika’s escape from her parents, which might allow her to finally choose her own identity (in the next scene, we see Evridika running down the street, the most active state we witness her in throughout the entire film). At the same time, the ending suggests that Saakyan’s poetic tale has certain limits that cannot be exceeded. The taboo of incest will not be broken even if it demands a Deus ex machina to avert it. While the way the ending unfolds does not make sense in terms of cause-effect logic, in this subjective poem it does, professing that this is not a Greek tragedy and Evridika will not end up having an epic tragic destiny, instead being to allowed to break free, if with the help of godlike intervention by the director. Still, while the ending may thus be interpreted in a purely symbolical and metaphorical way, the perfect resolution it brings dangerously abandons the complex deconstruction of narration as well as its ongoing uncertainty, both of which were core elements of the film up to this point.

Leave a Comment