On the Knife-Edge

Adam Martinec’s Our Lovely Pig Slaughter (Mord, 2024)

Vol. 146 (Summer 2024) by Oyku Sofuoglu

In a world where billions of animals are killed for human consumption every day and where this is considered normal and necessary by most people, it seems peculiar that the slaughter of a single animal can occasionally become a matter of great importance. This must have been what Czech filmmaker Adam Martinec thought when he decided to make a film that centers on the famous pig-slaughtering tradition from his home country. Known as “zabijačka” in Czechia, with different designations across Central and Eastern Europe, pig-slaughtering is a practice rooted in communal and collective principles that, especially during hard times, brought families and small rural communities together around values like solidarity, empathy, and benevolence – values that, even long after those hard times have passed, continue to motivate many to engage in the tradition.

Yet, to suggest that people partake in these rituals with conscious reflection on their symbolic weight might be an overstatement, for traditions often persist not through deliberate contemplation but through the inertia of repetition. One may continue simply because it has always been done that way. In Our Lovely Pig Slaughter, Martinec takes this seemingly matter-of-fact premise and sculpts it into a minimal yet entertaining family drama that remains anchored in familiar binary contrasts – tradition versus modernity, men versus women.

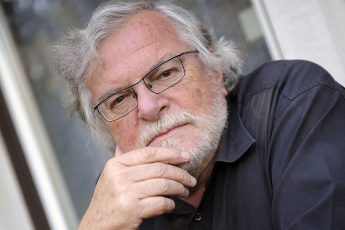

The story revolves around an extended family that, at the beginning of the film, we find immersed in the preparations for their annual pig slaughter and the ensuing feast – preparations that involve the female members of the household doing all the work in the kitchen, while the men drink and loudly complain about everything and nothing. The most enthusiastic among them is Karel – played by the director’s own father, Karel Martinec – who proudly acts as the head of the family, giving orders and ensuring that everything is done by the book. Not everyone shares his overzealous attitude, starting with his daughter Lucinda (Pavlína Balner), who gets scolded for things like not putting enough salt in the bread. But it’s Karel’s late wife’s parents who feel most on edge, wondering how they can tell Karel that they don’t want to raise pigs next year and that this will be their last zabijačka. Meanwhile, Tonda (Antonín Budínský), the butcher in charge of performing the slaughter, must work around cartridges that, despite constant precautions and appeals, have gotten wet – meaning, if anything goes wrong, he has to find an excuse to prove it’s not his fault, even though it actually is. The cherry on top is the family’s old and inexplicably hostile neighbor who threatens to report them to the authorities, since domestic slaughters are banned under European Union laws.

From a storytelling perspective, Martinec maneuvers through smooth and undemanding terrain, having set a central event as the narrative framework around which all the conflicts, tensions, and resolutions unfold. With few exceptions, the action takes place within the confines of the homestead, and we gradually become familiar with its spatial structure thanks to Martinec’s dynamic camerawork. Choral narratives are notoriously difficult to balance in terms of rhythm, especially within minimal, restrained spaces. While Our Lovely Pig Slaughter is hardly comparable to a tense and bustling family drama like Cristi Puiu’s Sieranevada, Martinec still manages to establish a realistic, smooth dynamic among his troop of non-professional actors – with a certain emphasis on and perhaps an unconscious proximity to the male characters. Although Lucie has a significant role in the story, particularly regarding her complicated relationship with her father and her exasperating husband Aleš (Aleš Bílík) – who fails miserably at imitating his father-in-law’s virile manners –, her characterization remains somewhat schematic. Given Martinec’s comments on drawing inspiration from his own personality and flaws to shape the male characters, the women in the film appear less like fully realized, authentic individuals and more like necessary counterparts to the men, meant to highlight the gender-based conflicts within the family.

The comedic aspects of the film are also predominantly reserved for the men, from Tonda’s silent nervousness to the hot-headed Karel, whose hastiness almost costs the family some of Grandpa’s favorite blood dishes – he slips and spills all the blood, prompting others to rightfully nickname him “Forrest Gump” – to the policemen, who initially came to investigate animal abuse but end up joining for drinks, with one of them turning out to be a vegetarian, much to the dismay of the group. Although some viewers liken it to Czechoslovak New Wave comedies, Our Lovely Pig Slaughter lacks the incisive irony and wit typically associated with the movement, instead relying on a more naturalistic sense of humor, making the most of the universally funny and chaotic side of family reunions. There’s undoubtedly a “Who’s going to save Christmas?” vibe to the film, but as we near the end, it’s contrasted with the fragile nature of these gatherings, despite the strong family bonds, and by the inevitable passage of time weighing heavily on everyone. Martinec’s revisiting of this peculiar tradition he grew up with warms our hearts, awakening similar experiences and relationships stored in our own memories. Yet, once emotions are set aside, one can’t help but notice how the nostalgic tone is imprinted on the film’s language itself – like in those moments when we stumble upon a film and feel a vague familiarity, asking ourselves, “Have I seen this before?” Our Lovely Pig Slaughter is full of such moments. It leaves us with bittersweet impressions, less about the story being told and more about how it was told and depicted, making us wonder if the outdatedness in its cinematic expression should be treated as a virtue or a weakness. Or maybe it should be treated as both…

Leave a Comment