“If We’re Not Here, There Won’t Be Any Children or Sweet Love.”

Alisa Kovalenko’s My Dear Théo (2025)

Vol. 153 (March 2025) by Jack Page

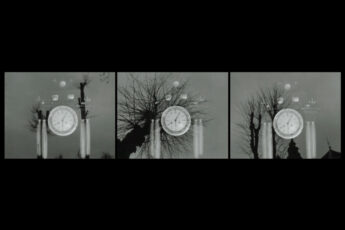

My Dear Theo is a personal and poignant account of life on the frontline with the Ukrainian volunteer army. Through firsthand mobile footage of daily military life interspersed with touching archival recordings of her young son, filmmaker-mother-soldier Alisa Kovalenko documents her squad’s journey through liberation missions in Kyiv and Kharkiv. Her voiceover recites the letters she has scribed to her son, explaining their progress, their struggle, and their unwavering faith in joining the fight to protect their country. Above all, these citizens have enlisted to ensure the freedom and future of the children that they left behind at home.

One of the most resonating aspects of the film is the pedestrian nature of the volunteer soldiers. They are family members, lawyers, musicians, gym instructors. There is no montage that details their transformation into cold-blooded killers. They are fallible, untrained, and unprepared. They are missing specialized knowledge and physical strength that is expected of regular soldiers. They shuffle instead of marching and drop their rifles in front of an exasperated instructor during training exercises, who screams “I’m scared to let you out!” in their faces. Yet their patriotism and camaraderie are unmatched. As Kovalenko states, “you become a continuous nerve.” I believe this smartly alludes to not only the teamwork and closeness in the squad, but also the universal feeling of dread, a heightened nervousness that threads throughout the soldiers, tying them together. The squad is acutely aware of their unreadiness to fight, which only proves their bravery. There is doubt and vulnerability in their eyes as the camera lingers on their reaction while the sound of shelling becomes louder, shaking the bunker. In the aftermath of a failed liberation attempt to de-occupy a local estate, there is a shared feeling of inertia and despair, the team now stuck in a village, the men wounded and concussed. One particular altercation in the trenches illustrates the high pressure and extremely dangerous environment of the frontline. Lacking technically superior equipment, the soldiers must rely on their hearing: “In the thick of the trees our ears become our eyes.” Glued to the radios in the dugouts, the squad collectively hold their breath as they wait for a reply. The crackling signal blurts out elliptical information – “stay in the shelters, damn it!” and “one wounded, one dead.” The fuzzy audio is even more incomprehensible over the popping of gunfire and explosions. Yet it’s not the expletives or the content of the dialogue they fear but the radio silence. The absence of a reply could indicate death, capture, and failure of their mission. One of the more wizened and experienced soldiers rationalizes the situation succinctly: “When the artillery is working, the infantry rest… there is always more loss in offense than defense.”

This life of violence and unpredictability is now their everyday reality, described by Kovalenko as “one long endless day.” Ceaseless gunfire, jet engines, and bombs have replaced the sound of birdsong and crickets. The wind-rustled leaves of the forest are now smoking, ashen grey and smoldering from the mortar strikes. Once familiar domestic settings are hollowed out and stripped of life. These deserted, dilapidated interiors and their collapsed walls are a ghostly reminder of the soldier’s mortality, littered with artefacts of the already dead. Interestingly, these battles occur in the idyllic countryside, rustic farmhouses and quaint villages that have become what Kovalenko refers to as “a ruin of a ruin.” These images are not typical war zones but school gyms and children’s bedrooms filled with weapons and survival kits. Even aesthetically, it is as if the war is quite literally infringing on the private and personal spaces of the ordinary Ukrainian family. Since the younger generation Kovalenko and her unit intend to protect and serve are not yet mature enough to understand their plight, the military unit’s endeavors go relatively unthanked. However, in a tender display of appreciation, all the village locals line up on the side of the roads, kneeling in respect and waving the convoy in gratitude as it passes through the streets.

The final somber sequence of the film is a dedication to “all of the parents who sacrificed their lives to defend the future of their children.” A montage of almost all members of her previous squad reveals that her friends and comrades have either been killed or gone missing in action. The audience has followed these characters throughout the documentary, witnessed their boyish charm as they roughhouse in the fields and ponder what they miss most about civilian life. We have seen their FaceTime calls to their loved ones and the smiles their children’s voice brings. We have heard them discuss how upon their return they cannot wait to play with their pets and kiss their wives. It is a tragic conclusion and a stern reminder of the real risks these volunteers sign up for. It is difficult to find promise in wartime, but Kovalenko’s final shot drops an optimistic hint for the viewer. A static, extremely low angle frame captures the aftermath of their HQ building that has recently succumbed to air strikes. The ground is strewn with dirt, rubble, and bricks. Weeds are spotted around the crusty earth and a sliver of light cuts through the wall of dust to reveal a busy nest of ants. Veins of fresh green plant stems emerge, breaking through the cracking mud. They symbolize a sign of life, of hope, that even in such devastating circumstances, among such decay and destruction, things can still grow and life will continue. For Kovalenko, however, it is still a long way from home and peacetime before she can be reunited with her dear Theo as she promises to fulfil her duty as a mother and a fighter.

Leave a Comment