A “loverboy” is a man who seduces young women and then convinces them to sell themselves. He is the middle-man between procurer and prostitute, he serves as a sort of talent scout for the pimp. Loverboy is Mitulescu’s second feature film after The Way I Spent the End of the Wold that was also screened in the “Un certain regard” section of the Cannes Film Festival. Luca, the “loverboy” in this film, is played by George Piştereanu, his target Veli is interpreted by Ada Condeescu, who some might remember from If I Want to Whistle, I Whistle. Luca is a semi-professional mechanic working and living in a garage at the side of a road near Constanța at the coast of the Black Sea. Although one of the oldest towns and therefore one of the places most visited by tourists in Romania, the region is also well-known for its deserted run-down towns, poverty and prostitution.

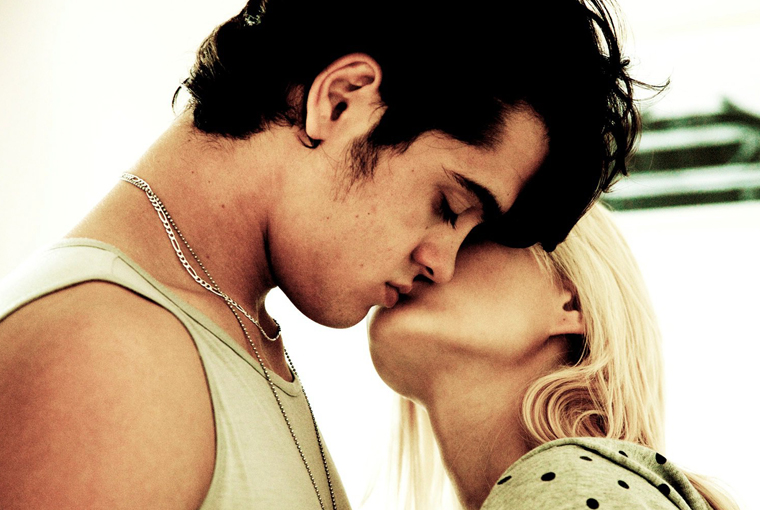

Loverboy neither attempts to document sex-traffickers nor does it give details about the infrastructures of this violent but tolerated profession. Mitulescu’s film is a love story and its tragedy has more to do with love than with the lascivious appetites of men driving fancy sports cars. “Sex doesn’t matter”, says Luca and indeed, on the rare occasions that we see him have sex, he seems rather suffering than enjoying, as if sleeping with his girlfriend were some kind of burden.

Veli is a shepherd’s daughter and lives in a hut that is not connected with the neighboring civilization by recognizable roads. Her family seems to have traditional values, but even if we do not get to know her family well, we are not surprised that her father, with his lambs and his wool sweater, would doubt the motivations of his daughter’s friend, driving a scooter (without a helmet), wearing sunglasses inside the house, and being afraid of a lamb slaughter but not of the knife used to do this.

Veli is innocent, and full of good intentions. She wants to turn the rest stop next to Luca’s garage into an admirable restaurant, she dreams of painting the walls and replacing the plastic table cloth with real tissue. When her father tries to steal her back violently, she is forced to decide between her family and Luca, although her father gives the impression that he would take her back, saying “you will come back on your own.”

So we have to believe that it is really love that lets her end up in a hotel room, not far away from the garage, probably on the same road where she saw herself spending a life with Luca. In an attempt to explain prostitution, one might be compelled to rationalize the trade of sex and money with unfavorable social or economic conditions, or violent force of others (mostly males) that leave the woman no choice but to sell herself. In Loverboy those arguments are hard to defend. Yes, Veli is definitely not rich, and the reason she decides to sleep with Luca’s friend, is because Luca needs money. On the other hand, she does not seem to depend on the money, nor is she particularly interested in the things that that money could buy. It is also obvious that Luca does not threaten Veli to prostitute herself. On the contrary, he even asks her to leave more than once, perhaps trying to protect her from this fate. It is also hard not to mention that when Veli actually sleeps with Luca’s friend she does not seem to suffer- Mitulescu could have easily shown an impassive objet de désir rolling her eyes…(although we don’t know if Veli just knows how to act, or if she’s pleased knowing that this will help Luca).

If then, prostitution can be a matter not only of choice, but of love, which however is rarely a matter of choice, then you might end up as confused as I am trying to make sense of this film. As a matter of fact, the conclusion is rather scary, and we might sympathize with Luca who is too afraid to visit Veli in the hotel room, too afraid perhaps to visit himself. He thus tries to protect himself, riding away (this time wearing a helmet).

Leave a Comment