A Journey from Life to Death, and Probably Back

Karolos Zonaras’ Tranzit (2023)

Vol. 142 (February 2024) by Margarita Kirilkina

Father and son commit suicide. This is how Tranzit by the Greek director Karolos Zonaras begins. From here on, both find themselves in a colorless space with arid soil, a sort of Platonic cave where only shadows from the real world remain. At the same time it is Tarkovsky’s Zone – a magical place governed by its own laws. This is a transitional space between the material world and the bodiless realm. Here, no one has names, and there are Guides whose duty is to accompany the recently deceased to some other metaphysical world, to well-defined eternity, where they will dematerialize forever.

The geometric figure of this space is Euclid’s circle, symbolizing perfection and, at the same time, the hopeless cyclicity of life and death. The circle is also a reference to Dante’s depiction of hell. Those who have just arrived seem to perform a ritual, moving along straight lines, then repeating the form of a circle drawn on the dusty ground. The Professor is the only one who resists the ritual logic of that mathematical microcosm. He lags behind, suffering of not knowing the reason of his death – suicide or murder, the two possibilities for those who find themselves here. He decides to find a way out of the Zone using its own method, mathematically calculating the escape formula.

Meeting for the first time in the transit zone, the father and the son initially ignore each other, but overcoming several critical situations, the son joins the father, along with others, with the intention of returning to life. Their journey from life to death leads to a transformation of their relationships. The son proposes to be the first to experience his father’s calculations, and the father agrees, making the son a victim who has placed his life at the mercy of fate. But can one die twice?

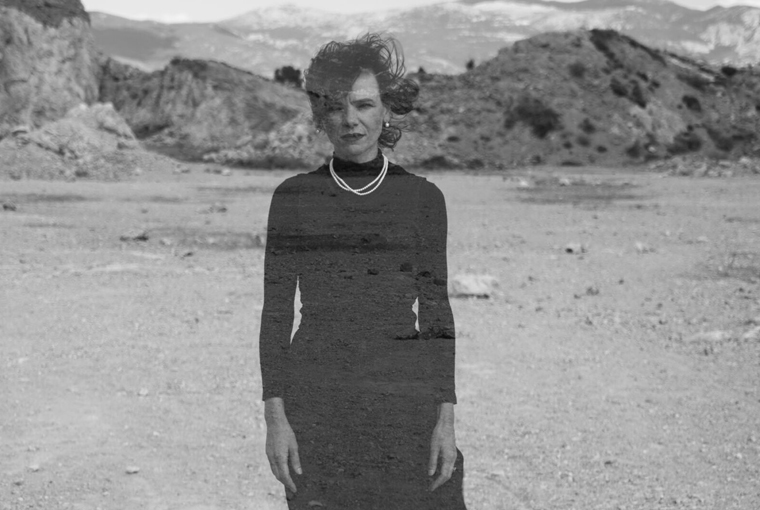

The black-and-white color of the film, the aesthetic of lifelessness, dry plants, still life, and sharp rocks, reflects the inner world of the characters. It is the state of a dead body still existing in the physical world. The only person in the film who does not belong to this space is the Woman. She doesn’t have a clear form, her body is transparent. She is at the same time here and in another dimension. She is an image or a product of imagination. She is visible only to the Professor, and becomes his Messenger. She is an exception in that calculated space, she is love, which belongs to the sphere of sensuality. It is her who reminds him of his past life in the world of feelings, a space of life. It is her who makes him obsessed with the idea of returning.

All these layers make the film rich in meanings, whereby every sight, every detail becomes a symbol. Perhaps, the dead bodies of the two suicided men in the first scene in color refer to the self-destruction of the collective body of humanity. Through their gesture, the two men remove themselves from a world characterized by shades of feelings to transition to a colorless plane where everything is calculated, and every movement is regulated. This is a space without freedom, a space of death. If Tranzit is an allegory for the way that contemporary society has brought itself to self-destruction, it links this self-destruction to the total rationalization and calculability of today’s world. The Woman in the film is the last remnant from our past, or perhaps a sign of our future. She is probably the Mother, the beginning of life. Is there hope that we escape self-destruction and embrace life again? Karolos Zonaras doesn’t offer any verdict on this question. The ending remains open.

Leave a Comment