In Search of Freedom

Klára Tasovská’s I’m Not Everything I Want to Be (Ještě nejsem, kým chci být, 2024)

Vol. 144 (April 2024) by Sonya Vseliubska

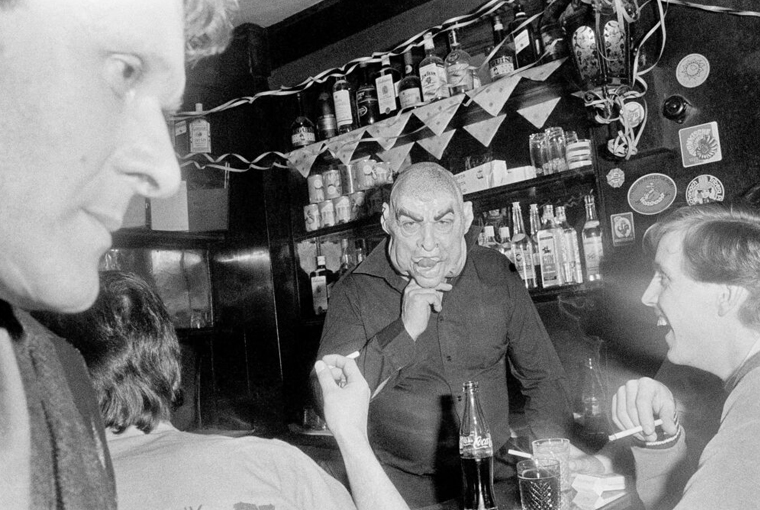

Prague-born photographer Libuše Jarcovjáková has dedicated her life to capturing the gritty reality around her. Back in the 1960s, as the country was struggling with concerted Soviet oppression, she decided to devote her youth to her creative journey. Her photography is known for documenting marginalized, neglected, and suppressed aspects of reality, such as the city’s nightlife, the everyday of migrants, or political protest movements. Or a perspective even more marginalized in authoritarian societies – a selfish preoccupation with oneself, with one’s own yearnings and desires. The motifs and cities around Libuše have changed over the years, but her particular style has always remained true to itself. Libuše documents her surroundings with the utmost honesty, yet balances out her outward leanings with an equally liberated process of self-documentation. This continuous capturing of both inward and outward reality was preferably black and white in the literal and symbolic sense. The basements of gay clubs were as rich in contrasts as her photographs that tended to resonate with the aesthetics of Czechoslovak documentaries of the period. This was Libuše’s artistic mission, the story of which only Klára Tasovská was permitted to tell, making her film the greatest celebration of the photographer to date.

One of the most difficult tasks in a documentary is finding a way to approach the creative protagonist, whether it is in an act of celebrating their very existence or through an attempt to emphasize a specific aspect of their being. Films have covered these extremes and everything in between in every modality of a documentary, from the observational to the performative, not infrequently failing to preserve the sense of the uniqueness of their protagonist in the process. The film I’m Not Everything I Want to Be is a rare case when a film is not only able to tell the voluminous story of an artist, but also conveys with its film language how their protagonist creatively expresses themselves – literally, how they express themselves in their own language. Tasovská does this in her film with a directorial approach that is both phenomenally simple yet very difficult to realize convincingly – she gives her heroine complete freedom of expression in her documentary, allowing her thoughts and creativity to shape the filmic space.

I’m Not Everything I Want to Be is a beautifully compiled, diachronic slide show that is overlaid with the heroine’s voiceover of her revisiting her own diaries. The story in the film begins with the first discoveries in the Libuše archives from the late 60s – the time when Russian tanks entered Prague and Libuše’s maturation as a woman and photographer began. While observing the shifting reality of her city, she learns to take photographs, and thus forms her creative specialization, which will have a decisive influence on her destiny. Whether the heroine is in her hometown while in her 20s or working on an exciting project in Japan years later, the photographs from each period reflect a journey of constant research, reflection, and development that never stops. At the end of the movie, she states that she will probably never stop wondering who she really is. Thus the journey that Libuše embarks on does not end with the film, but points beyond its own limits.

Tasovská minimizes her directorial presence in a way that mitigates the ethical dilemma of exposing personal diaries to the public. The fact that Libuše in a sense takes over the film echoes her character, which is why it is almost impossible to imagine another form of documentary about her. The story of a bisexual photographer developing her creative voice against the backdrop of a collapsing Europe while traveling and seeking sexual freedom, conveys a sense of rebellion lurking everywhere, which is enhanced by the enduring spirit of both youth and desperation. In some way, it feels like an aftermath of the Czech New Wave, with Libuše spectating her own story from the perspective of a family friend. After the Prague Spring, the local cinematic culture with its innovative young names mixing in criticism of the state with their surrealism would soon be oppressed. As this generation was forced to hide away in basements, Libuše was the kind of photographer to capture what was happening in these very basements on film. Being in a state of prolonged melancholy, the combined factors of which were national as well as personal problems, she drew inspiration from the faces of those who suffered from this period along with her.

It is paradoxical that Tasovská is able to enhance the atmosphere of the story despite working with pre-existing material. Tasovská was able to almost animate the photographs, to enrich static images with a voluminous cinematic form through the use of soundscapes and editing. The static and flat nature of the photographs recedes into the background and a diegetic space is created by contemporary music, while the rhythm of the periods of the heroine’s life is conveyed by the pace of the slideshow’s cadences – rapid changes of shots during work proposals or romantic encounters are replaced by slow slideshows during depressive episodes. Tasovská greatly accentuates not only rhythm, but also the persistence of her heroine’s pondering existence. The film’s chronological narrative points to a dynamic that never ends, and this is where the universality of the film lies. I’m Not Everything I Want to Be is a story of finding freedom, wherein the constant search involved is as essential as the purpose it aspires to.

Tasovská has a great appreciation for what one could call Libuše’s “simple” photographs – shots taken in the mirror, often of the naked body and with the face preferably covered by the camera – and delicately constructs the recursiveness of these moments. Thus, in the midst of photographs of random people and streets of different cities, the film keeps returning to Libuše documenting herself as she reflects on her identity or her sexuality in the shackles of the political apparatus. Whether Libuše is in her 20s or already a successful artist who happens to be active on the other end of the world, she keeps re-evaluating herself in the mirror and begins to manifest an acceptance of herself. Libuše has never been afraid of imperfection, and this is what makes her such an interesting photographer and an extremely enviable subject for a documentary portrait. Tasovská, for her part, is not afraid to face all aspects of a story, including imperfect ones, which is where her charm lies.

Leave a Comment