I Is Another

Klára Tasovská’s I’m Not Everything I Want to Be (Ještě nejsem, kým chci být, 2024)

Vol. 146 (Summer 2024) by Oyku Sofuoglu

Documentaries about the late or posthumous recognition of artists represent a popular and prevailing trend in both mainstream and arthouse cinema, fueled especially by the efforts of queer, feminist, postcolonial, and intersectional movements to reverse the systematic erasure that minority groups have been subjected to across various fields. With respect to the field of photography, notable examples of this tendency are John Maloof and Charlie Siskel’s Oscar-nominated Finding Vivian Maier and, more recently, Laura Poitras’ Golden Lion winner All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, which focuses on American photographer Nan Goldin’s life and her long, ongoing fight against pharmaceutical companies that caused the opioid crisis in the 1980s and 1990s. Although Maier’s case is an exception in the sense that she never considered herself a photographer, films about unrecognized talent and its intrinsic connection to the institutional, social, and political privileges that predominantly benefit white, male, and heterosexual artists usually follow a similar narrative formula. These films do not necessarily aim to tell a success story in the original sense of the term, but work as a conceptual and artistic tool to give these artists what they had deserved in the first place – becoming part of the canon and being counted among those who had once ignored or rejected them.

Premiering at this year’s Berlinale and then traveling across other film festivals including Karlovy Vary, where it had received a Work-in-Progress award last year before its completion and release, Klára Tasovská’s first solo documentary I’m Not Everything I Want to Be constitutes a peculiar example of artist documentaries. Tasovská’s film tells the story of Libuše Jarcovjáková, a Czech artist who, throughout her adult life, struggled to make a name for herself as a photographer. As she drifted across the cities of Prague, Berlin and Tokyo, she tried capturing authentic and honest images not only of people she encountered but also of herself. As a woman artist who had lived under the domineering shadow of the Iron Curtain in the seventies and eighties, Jarcovjáková had gone through ever-present feelings of self-doubt, worthlessness, and loneliness. As of now, even though she remains relatively unknown to the mainstream public, one can say that she is met with acceptance and respect as a photographer, as reflected in a major exhibition of her work at the 2019 Rencontres de la photographie d’Arles, one of the most important international festivals of photography.

It is also this exhibition that serves as the film’s entry point to Jarcovjáková’s life, announced at the very beginning by Jarcovjáková herself via voice-over with a charismatic, calloused voice that echoes decades of hardship, but also of booze and tobacco. Without dwelling much on the present – which is only revisited for a few minutes at the end of the film –, we’re transported back to Prague in 1968, where we find a young Jarcovjáková, whose dreams of enrolling in a film school are hindered by the ideological requirements of the Communist regime. On the very surface level, the narrative structure of the film is rather straightforward since it’s built linearly – unlike Poitras’ film, whose structure consists of going back and forth in time. Yet the narration itself, layered through disparate sound and image sources, is by no means simplistic. From the beginning to the very end, accompanying Jarcovjákova’s voice is a vast selection of still photographs she shot throughout the years. I’m Not Everything I Want to Be is certainly the fruit of extensive and in-depth archival research, followed by an equally meticulous editing process. In film theory, the insertion of still images within a film is often seen as a way to remind viewers that the essence of the cinematic medium is the photogram. However, in this case, it’s as if the film itself is like a manual for understanding the methods and techniques that can be applied to still images in order to activate the dynamism they possess in potentia. The rapid alternation of photos; originally monochrome visuals being subjected to constant color changes; and the use of stroboscopic effects or split screens, are just a few examples of the deployed techniques that create the impression of motion in the image. Yet it is essentially by virtue of the vividness, spontaneity, and overarching sense of punctum inherent in the very fabric of Jarcovjáková’s photos that these techniques succeed in setting the cinematic image in motion, so to speak. Color, light, and shadow – with these, it’s easier to emulate movement as an abstract phenomenon. But what about movements that arise from actual sensorial experiences? That’s where elaborate sound design comes into play, adorning the frame with spatial and directional properties – organic or mechanical sounds approaching, withdrawing, crashing into one another and traversing through the depth of field.

I’m Not Everything I Want to Be is designed to be as immersive as possible for the audience, guided by Jarcovjáková’s own voice and led through her own images. It shouldn’t surprise us that an artist is given a narrative carte blanche in a film that tells her story. Yet it is equally valid to inquire about the filmmaker’s whereabouts within the film, as it has always been tricky for directors of artist-centered films to decide to what extent they should highlight – or conversely, conceal – their own artistic personas. In Tasovská’s case, although we learn that she wrote the voice-over narration, much of which was inspired by Jarcovjáková’s own diaries, it seems she opted for the latter approach, favoring a direct and transparent form of narrative address that centers on Jarcovjáková’s perspective as opposed to her own. Still, this narrative frame feels more organized and constructed than it should, largely because both the film and Jarcovjáková reflect on her life from a contemporary standpoint. There is no doubt that any act of remembrance is a rewrite of the past, and that pure, unmediated memory does not exist. Yet, the film seems less concerned with acknowledging this temporal friction, instead acting as if there is a seamless unity between the way she lived her life and the way she now interprets it.

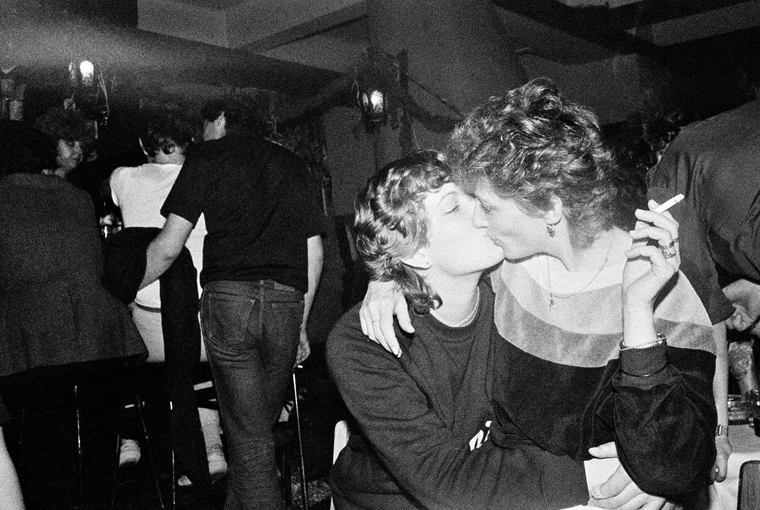

A relatively more unvarnished look at Jarcovjáková’s self-expression can be found in the way she photographed herself over the years. As a woman whose body and face fall outside what was (and still is, to some extent) considered the aesthetic norm, Jarcovjáková’s almost obsessive habit of photographing herself feels self-affirming, especially because it was never an impact she consciously sought. In her own words, she used the camera as ‘a navigational tool’ to help her return to herself. She photographed her face because it is her face, and her body because it is her body – not because they looked beautiful, ugly, old, young, or anything else. Her self-portraits, therefore, were not created to serve as signifiers for social, political, or gender-related categories – nor were the photos of her coworkers that she took at the print factory, on the street, in pubs, or in the T-Club, which is now seen as a lost cornerstone of Prague’s underground queer nightlife.

It would be unreasonable to expect an artwork to remain isolated, immutable, and frozen by the artist’s personal intentions. Photographs may be still images, but their lives move on whether we like it or not; they become woven into larger narratives or are used to build new, alternative ones. This is what happens when the media describes Jarcovjáková as the “Nan Goldin of Czechoslovakia,” when the film gets summed up as the story of a “tormented, visionary artist who lived under the repressive Soviet regime,” or when intimate, personal confessions become tagged and indexed under categories. While watching Tasovská’s film, it’s hard not to wonder about those photographers yet to be discovered but who likely never will be, and others who eventually will. By whom, and through which political, social, ideological, and economic mechanisms, does cultural memory operate? While these mechanisms – once hidden beneath the abstract concepts of discovery, recognition, and acclaim – have become more conspicuous today, I’m Not Everything I Want to Be merely brushes the surface of the subject without fully engaging with it. It’s unclear whether this is partly because the film itself benefits from these mechanisms. Yet, when we consider the title, its unintentionally autological nature reveals something telling: the film is not everything it wants to be…

Leave a Comment