I. On Soviet Cinema and the Question of Fate

Soviet documentary cinema was a cinema of positions, not fates. Even in biographical documentaries, fates were not explored: the protagonists were only outstanding individuals, and a person’s fate was merely an appendage to the special social position of the distinguished figure that the director needed to showcase. A great person, even if they were still alive and speaking on camera, was presented as a marble bust. A person’s fate was viewed as a series of achievements – and in this sense, the biographical genre was a continuation of the historical genre, which also dealt exclusively with the great. In line with the Soviet glorification of labor, the popular Soviet genre of the “ode to a profession” (or its variation, the “ode to a professional”) belonged to the same paradigm, and thus films about firefighters and fishermen participated in the discourse of greatness. The “ode to a profession” genre flourished even in the late Soviet period – see, for example, Herz Frank’s films The Salt Bread (Sāļā dzīve, 1964), Trace of the Soul (Mūžs, 1972), Diagnosis (Diagnoze, 1975), Another’s Pain (Chuzhaya bol’, 1983) – though such a perspective obviously provided very limited access to the subject. In the case of portrait films, the off-screen voice would recite the protagonist’s ‘official’ biography, usually emphasizing a fairly standard set of personal qualities that allowed them to overcome the hardships they faced and realize themselves in their beloved profession. If it was a collective portrait – say, a film about a factory – then there was no mention of biographies, let alone fates. The profession quite literally became the protagonist, mechanically embodied in people. Therefore, the most original films shot in this genre were those that, starting from the professions of their characters, managed to lead them into another plane. This was done in various ways: Leonid Kvinikhidze (Marina’s Life/Marinino zhit’yë, 1966) and Lyudmila Stanukinas (The Tram Runs Through the City/Tramvay idët po gorodu, 1973) portrayed their heroines in an extremely personal way through everyday speech. Tofik Shakhverdiyev, in Gymnastics Lessons (Urok gimnastiki, 1973), stripped the profession of its utilitarian veneer and presented it as an obsession. Pavel Kogan and Peter Mostovoy, in Military Music Orchestra (Voyennoy muzyki orkestr, 1968), made a formal discovery by revealing the cinematic effects that emerge at the intersection of the musician’s and the soldier’s professions.

However, freeing oneself from the shackles of Soviet genre clichés was not enough, and this liberation brought no particular freshness. Where it did occur, a content void emerged: documentarians continued to film the same things – the same fishermen, the same workers – but now, with the ideological pathos gone, what remained – marketed as ‘life as it is’ – often felt aimless and lacking in substance. They showed fishermen (see the 1996 Fisherman’s Happiness/Rybatskoye schast’ye by Vladimir Eisner), but it was unclear where to look and what was interesting about it. And quite naturally, in a place where the eye had nothing to latch onto, knowledge took root – because where nothing interesting happens, something is still happening, meaning there is something to learn. This became the new paradigm of documentary filmmaking – the documentary film as a way to ‘expand one’s horizon.’ Science replaced Soviet ideology. It is here, I believe, that we find the roots of the scientific-popular, anthropological-ethnographic cinema that would flood television and come to define the programming of channels like Discovery – a refuge for desperate romantics with an adolescent mindset, awed by the richness of the universe and convinced that every educated person must know how people live in Africa, how reindeer herders survive in the taiga, and how fishermen make their living on Lake Baikal. As early as the late 1980s, this type of documentary filmmaking was mocked by the Aleynikov Brothers in Tractors (Traktora, 1987), and later by Sergey Kuryokhin in the television segment Lenin Was a Mushroom (Lenin – grib, 1991), as well as Sergey Debizhev in Insanity Complex (Kompleks nevmenyayemosti, 1992).

It was precisely this context that served as the backdrop for what Sergey Dvortsevoy (Happiness/Schast’ye, 1996; Bread Day/Khlebnyy den’, 1998; Highway/Trassa, 1999), Vitaly Mansky (Grace/Blagodat’, 1995), and Victor Kossakovsky (The Belovs/Belovy, 1993) did in the 1990s with their early films. Formally, their stance was in many ways similar to that of the aforementioned ‘scientific’ filmmaking. Their films were also a kind of fieldwork, forays with a camera into the semi-wild or at least exotic everyday life of the Russian (and, in Dvortsevoy’s case, Kazakh) people – a way of life that, for the general audience, was and remains akin to that of indigenous tribes. However, if these films never found their own Discovery Channel, it was because a step was taken – a step away from exoticization, from the perspective in which one observes another person’s life as a curiosity, as one might observe the life of insects. It was the same step that had been taken somewhat earlier in Western anthropology by Edward Said and Claude Lévi-Strauss. “Look how I live here,” says a Kazakh steppe nomad in Happiness. “Fuck this. What a shitty life. What, my whole youth will pass in this steppe with the sheep?” This was the first way to balance out the excess of exotic images – through speech that was very familiar. The second way concerned the approach to the material. Where a Discovery Channel documentarian sought out ‘savages’ engaged in some incomprehensible ritual or cooking some extraordinary dish, Dvortsevoy filmed a little Kazakh boy sitting on the floor, eating porridge from a bowl. In this way, Dvortsevoy showed that he had something to add to a scene that had marked the beginning of cinema a hundred years earlier – when a baby from a bourgeois Parisian family ate porridge on film.

Major milestones in this regard were Viktor Kossakovsky’s films The Belovs (1993) and Wednesday 19.07.61 (Sreda 19.07.61, 1997). The Belovs was the pinnacle of an approach that worked with speech. It was access to the spontaneous speech of the protagonists that opened the audience’s eyes to the fact that life in the depths of the countryside was, in many ways, no different from that in intellectual St. Petersburg families: women bore the burden of daily life while their men were consumed by megalomania. Wednesday 19.07.61, by pushing the genre of social cinema to the point of absurdity, effectively dismantled it in the form in which it had persisted since the 1980s. In this film, Kossakovsky filmed seventy residents of St. Petersburg who were born on the same day as he was. Each episode lasts no longer than a minute. In their allotted time, people say things like: “Our cat fell from the ninth floor. Three times. Survived. No injuries at all.” Or: “Well, I live alright. So far, everything is fine. Who knows what the future holds. The weather is bad, though.” One person is getting their toilet fixed; another is having their dog neutered. Kossakovsky radically questioned what could serve as the subject and substance of a documentary film, thus taking a step away both from Soviet television documentaries of greatness and from social cinema of fixed roles, toward the kind of cinema that would later be formalized in the method of Marina Razbezhkina and Aleksandr Rastorguev. The people appearing on screen share nothing but a date and place of birth. Yet this alone proves sufficient to speak about an ordinary person not as a representative of a social class, a milieu, or a professional community, nor as a figure in some predefined ‘narrative,’ but as an individual with a fate. And this is where the new documentary cinema begins. In Kossakovsky’s early film Losev (1989), Russian philosopher A. F. Losev formulates this shift in his own way when speaking about fate: “It is an entire doctrine. I have developed it as a doctrine. Of course, I could never express it anywhere… In systematic form, until ’87, for seventy years, it was impossible [to express it].” The same had been true for documentary cinema.

II. On the Voice-over

In pre-perestroika Soviet documentary cinema, which was generally quite monolithic, there were two anomalies – two letters from the future: Look at the Face (Vzglyanite na litso, 1966) by Pavel Kogan and Sergey Solovyov and Ten Minutes Older (Starshe na 10 minut, 1978) by Herz Frank. Today, these two ten-minute films are not particularly interesting to watch. Nevertheless, they have firmly secured their place in film history due to the methodological shift they attempted to introduce.

The Kogan/Solovyov film begins with a scene in a museum, where a tour guide says: “Look at the Madonna’s face. It is beautiful.” The film’s title appears, echoing the guide’s words. But it soon becomes clear that the director is not inviting us to look at the Madonna’s face, but rather at the faces of the people looking at the Madonna. The face of the Madonna and the faces of ordinary Soviet citizens visiting the museum are placed on the same plane.

This is how the film is usually described. For some reason, everyone forgets something far more interesting than all those faces – the speech of the tour guide. The film’s editing does not allow this fact to be ignored or regarded as accidental. There is nothing accidental about the choice of not just a museum setting, but specifically a tour setting, because this is precisely the context in which a Soviet documentary film viewer typically found themselves. They were shown workers laboring at a construction site while a voice-over narrator said something like: “Look at the faces of these people, working up a sweat to build Soviet cities! How much selflessness, how much titanic willpower is written on the features of these simple Soviet workers.” But this did not necessarily have to take on an overtly propagandistic form, because the issue here is not propaganda. What is actually being said? Exactly the same thing the tour guide says: “Look at the faces of the workers. They are beautiful.” It is precisely because this is not about propaganda, but about the position of knowledge in relation to something fundamentally ambiguous, that the situation with the voice-over narration remained largely unchanged not only during the Thaw and perestroika but also in the post-Soviet period.

Look at the Face was an avant-garde film not because we were invited to admire the faces of fellow citizens instead of the Madonna, but because it posed the question of the position of knowledge in documentary cinema. And the viewer was invited to determine the significance of this question for themselves – the film was constructed as a montage experiment, akin to Kuleshov’s experiments. This experiment had four phases: for the first four minutes, the speeches of tour guides from different groups flow in an uninterrupted stream; then, for another forty seconds, we hear the voices of foreign tour guides; then, for more than two minutes, the speech disappears entirely before returning at the end of the film. The audience is invited to look at the faces of the people in a sequence of contexts: comprehensible speech – incomprehensible speech – absence of speech – and to draw their own conclusions about whether they are seeing the same thing each time or not. Clearly, this sequence shapes the viewer’s perception of Kogan’s film (that is, of the faces themselves) in much the same way that the tour guide’s speech shapes museum visitors’ perception of the face of the Madonna.

It is no surprise that when, twelve years later, Herz Frank ‘modernized’ this experiment in Ten Minutes Older (1978), he once again found himself at the forefront of documentary filmmaking. At the time, the dictatorship of knowledge in documentary cinema was still invincible, and the avant-garde is always about fighting the invincible. But for Frank, this gesture became symptomatic. By the 1970s, something in his cinema was clearly beginning to go wrong with the voice-over narration. In his Forbidden Zone (Aizliegtā zona, 1975), a film about juvenile delinquents and social justice, the defining phrase of the narration is: “But on the other hand…” Despite the selfless work of the juvenile detention center’s warden – a true professional – one of his wards, upon being released, openly states that he intends to continue to steal. Frank’s voice-over, with strained indignation, comments: “If this is just bravado, he will come to his senses in time! If he’s serious – then this is how his life will pass, behind bars!” All of this sounds unconvincing, and there is a feeling that the director himself would be happy to stop talking – but obviously, it is not that simple. The same failure of moralizing occurs in The Meeting (Vstrecha, 1979) by Mostovoy, where the director revisits the fates of children he filmed ten years earlier in Only Three Lessons (Vsego tri uroka, 1968). It turns out that one of these children later became a murderer and was sent to prison. The teacher gathers his former classmates and, in true Soviet spirit, begins chastising both them and herself for not having “kept an eye on him.” It is decided that they should visit their classmate in prison. The meeting is awkward and consists of forced smiles and strained exchanges of school memories. This meaningless ritual is accompanied by a voice-over narration about how difficult it is to “cultivate kindness, attentiveness to others, and responsibility for all living things.” As in Frank’s Forbidden Zone, the voice-over fails to fill the gaping structural void. The culmination of this process – and simultaneously of Frank’s career – was The Last Judgement (Augstaka tiesa, 1987), also filmed in a prison. The conflict between what breaks through onto the screen and what can somehow be presented becomes irreconcilable. Then, in 1989, he and Vladimir Eisner made There Were Seven Simeons (Reiz dzīvoja septiņi Simeoni) about the Ovechkin family – seven brothers, each with their own musical instrument, living harmoniously in a village and playing jazz – until, one day, they hijacked a plane to escape to capitalism. Here was a series of events that could not possibly be narrated in the language of Soviet moral psychology. The exemplary Soviet working-class family, a phenomenon with a mother-heroine at its head – and these people hijack a plane, ready to die just to escape the USSR. This was simply too much. The very structure of the film marks this rupture. Its first part, filmed years before the hijacking, is a village idyll – a portrayal of the family as it needed to be presented. In the second part, filmed after the hijacking, Frank looks at the same footage differently: “The boys were ashamed of their livestock, of manure. The neighborhood kids mocked them, called them hillbillies. But journalists, including us, found this cute… We were searching for harmony here, for the union of labor and art.” For the first time, the voice-over narrator exposes himself. And when the demiurge no longer believes in what he is saying, his reign is over.

By the late 1980s, a different kind of social cinema began to emerge. The landmark film of this shift was Juris Podnieks’ Is It Easy to Be Young? (Vai viegli būt jaunam?, 1986), which created a bombshell effect by showing Soviet youth as they had never been seen before – lost, desperate, indifferent, but most importantly, ordinary, dreaming of an apartment and a car. It was the blow to the Soviet cult of greatness from which it would never recover. Podnieks’ film touched on themes that other directors soon picked up. Films began to appear about perestroika-era rock and punk culture and unofficial art, such as Ya-Khkha! (1986) by Rashid Nugmanov, Nastya and Egor (Nastya i Egor, 1987) by Alexei Balabanov, Dogs (Sobaki, 1987) by Vitaly Mansky, Rock (Rok, 1988) by Alexei Uchitel, Black Square (Chërnyy kvadrat, 1988) by Olga Sviblova, and Why Are You Gathering? (Zachem vy sobirayetes’?, 1989) by Alexander Pyatkin. Georgi Gavrilov made an uncompromising film about the lives of young drug addicts, Confession: A Chronicle of Alienation (Ispoved’. Khronika otchuzhdeniya, 1988). For the first time, the voices of young and forgotten veterans of the Afghan War appeared on screen in Return (Vozvrashcheniye, 1987) and Afghan Dream Book (Afganskiy sonnik, 1988) by Marina Chubakova. Valentina Kuzmina, together with the young Marina Razbezhkina, filmed And in Your Yard? (A u vas vo dvore?, 1987), a documentary about teenage criminal gangs in Kazan. Brick Flag (Vėliava iš plytų, 1988) by Valery Berzhinis sparked heated discussions about torture in the Soviet army. Tofik Shakhverdiev turned his camera to perestroika-era Stalinism in Stalin Is with Us? (Stalin s nami?, 1989) and later explored poverty and prostitution in To Die of Love (Umeret’ ot lyubvi, 1991).

The final nail in the coffin of Soviet social documentary filmmaking was Palms (Ladoni, 1993) by Artur Aristakisyan – an epic panorama of life at the very bottom of society, a chronicle of the homeless existence of a people who had lost their country. The moralizing tone that once accompanied social themes completely disappeared – filmmakers had nothing left to add to the words of their subjects, and the voice-over narration fell silent.

III. On Cinema Activism

The examples of new social cinema mentioned above, which emerged in the late 1980s, went beyond Soviet genre boundaries and shifted into a new dimension – a dimension of political statements. The films following such an activist approach anticipated the changes that the country was on the brink of in the early 1990s.

For obvious reasons, political documentary cinema was impossible in the USSR. Therefore, this kind of filmmaking began not with documenting political life, which did not yet exist, but rather with attempts at its emergence – in other words, various forms of activism. Since, in the thirty years following the collapse of the USSR, little progress has been made in the development of politics in Russia, this genre also evolved little, turning instead into a chronicle of political gestures – what Irina Sandomirskaya called an “archive of stolen revolutions.”1

The first films of this kind were made in Latvia – one of the first Soviet republics to seek independence. These included Homeland (Krustceļš, 1990), The End of Empire (Impērijas gals, 1991), and the multi-episode documentary epic Soviets (Mēs, 1989), all by Juris Podnieks. These films shaped the form that this genre would retain up until works like Winter, Go Away (Zima, ukhodi!, 2012), The Term (Srok, 2014), Kiev/Moscow (Kiyev – Moskva, 2015), Chronicles of a Revolution that Didn’t Happen (Khroniki nesluchivsheysya revolyutsii, 2016), The Case (Delo, 2021), Summer 2331 (Leto 2331, 2021), Welcome to Chechnya (Dobro pozhalovat’ v Chechnyu, 2020), The Age of Dissent (Vozrast nesoglasiya, 2018–2024), and others. From the very beginning, this genre also became inseparable from the consequences it entailed – two of Podnieks’ cameramen, Andris Slapiņš and Gvido Zvaigzne, were killed by Soviet riot police forces while filming in Riga.

This chronicle of activism became, in a way, an inverted Soviet newsreel. A monumental reworking of the genre took place in Soviets. Irina Sandomirskaya wrote: “Podnieks’ film crew roams across the homeland, just as official Soviet chroniclers once did – ‘from edge to edge,’ ‘from the southern mountains to the northern seas’ – but everywhere, instead of scenes of a thriving, peaceful life, they find traces of catastrophe.”2 Podnieks was indeed the first chronicler to film from the perspective of the future – from a position that could be called neither Soviet nor anti-Soviet, but catastrophic. Soviets begins with a reading of Mandelstam’s poetry (“Everything cracks and shakes”) and presents the viewer with an epic late-Soviet panorama of an empire in the throes of collapse: the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, protests in Riga in 1987, the Armenian earthquake and the Sumgait pogrom in 1988, the Tbilisi massacre in April 1989. The film raises uncomfortable topics such as the appalling working conditions in factories, mass self-immolations of women in Uzbekistan, and the war in Afghanistan. Against the backdrop of this crumbling Soviet façade, scenes from ‘peaceful’ life are interwoven: Andrei Sakharov’s return from exile, the celebration of the 1000th anniversary of the Christianization of Rus’, the daily lives of Latvian hippies, a Moscow circle of Bulgakov enthusiasts, and the patriotic organization “Memory.”

During these same transitional years, Vladimir Eisner shot a trilogy at the Siberian studio “Asia-Film”: Full Speed Ahead! (Polnyy vperëd!, 1989), Prayer (Molitva, 1990), and Quiet Abode (Tikhaya obitel’, 1991), which he later combined under the title Chronicles of the Time of Troubles (Khroniki smutnogo vremeni, 2017). Around the same period, Chantal Akerman traveled to Russia to film From the East (D’Est, 1993). These films completed the panorama of the transitional era first outlined by Podnieks. Unsurprisingly, the primary formal device used by Akerman was the slow dolly shot: the camera moves passively through the country, observing people in its fields, in its queues, at its bus stops – just as soldiers pass by the ruins left by a retreating enemy, watching the surviving inhabitants emerge to the roadside in some vague anticipation. This was exactly how Akerman moved through Russian streets, newly exposed to foreign eyes for the first time.

From the East was, in many ways, the final film of the Soviet era, its curtain call. Without a clear beginning or end, the film embodied the state of anticipation in which the country remained suspended. Exactly ten years after Akerman, Sergei Loznitsa would film Landscape (Peyzazh, 2003) – a work almost identical in form to Akerman’s film – and would find that, ten years later, the country was still trapped in the same uncertain waiting, in its fields, at its bus stops, and in its queues.

IV. On Myths and Wars

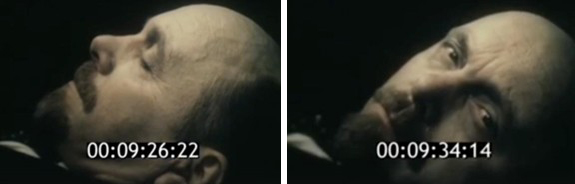

Immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union, films emerged that directly dealt with the theme of the Soviet legacy. Mansky’s film Lenin’s Body (1992) (the more literal translation would be Body of Lenin, as the reference is clear here) accurately marks the direction in which this legacy has been addressed ever since. On the one hand, it is a work of demythologization. In this film, the body of Lenin lying in the Mausoleum is seemingly given back its physicality – indeed, throughout the film, a sprawling scientific and technological infrastructure is described, necessary to prevent the body from falling apart. On the other hand, this critical demythologizing work led to only one conclusion – the discovery of a new myth: the post-Soviet myth about the Soviet past. The body of Lenin, the body of the dead father, acquires a special kind of power before our eyes, precisely because there is a corpse and someone is responsible for it. A scientist in the film says: “How much longer can Lenin’s body be preserved? Usually, we say: indefinitely. New people will come, who will be trained, they will preserve, they will observe, they will do everything necessary.” At the end of the film, the documentary plan is unexpectedly interrupted: Lenin, lying in the mausoleum, turns his head, opens his eyes, and looks into the camera. I wouldn’t rush to talk about the Soviet Union rising from the dead. The meaning of this image is far more literal – it is the gaze of the dead man, demanding an answer and assigning blame. It is precisely this demand that the Russian authorities will ultimately answer, telling the people who really killed the father.

The myth of the Soviet past would become one of the central themes in Mansky’s career – 26 years later, in Putin’s Witnesses (Svideteli Putina, 2018), he would address it in exactly the same way through the example of the Russian national anthem. This theme would be taken up by a whole new generation of Russian filmmakers as, throughout the 2000s, the drama I have called the “answer to the dead man’s gaze” would unfold with increasing intensity. The myth of the Soviet past would become an increasingly important reference point for the Russian government, which, despite what it may claim, would never want to resurrect the Soviet Union, as it is needed only in its distant, dead, and mythologized form. A peculiar echo of Lenin’s Body would come in Leninland (Leninlend, 2013) by Askold Kurov, about the Lenin Museum in the village of Gorki, and in The Wall (Stena, 2017) by Dmitry Bogolyubov, about how the anniversary of Stalin’s birth is celebrated every year at the Kremlin wall.

Of course, at the heart of the myth of the Soviet past is the war. Tofik Shakhverdiyev in The Victory March (Marsh Pobedy, 2000) showed that the culture of remembrance of the World War II in Russia is characterized by a kind of senile dementia; it is a culture of nostalgic pensioners, and it is on this basis that it has woven itself into contemporary Russian reality. The war – this open wound on the country’s body – has not been treated, it has been hastily bandaged with St. George ribbons under which it continues to rot. It is no surprise that in 2015, Alexandra Karelina made two films that form a thematic pair – one about the Victory Parade (0905) and the other about the Russian life of Soviet sanatoriums (Soviet Sanatoria). In Victory Day (Den’ Pobedy, 2018), Sergei Loznitsa drew a line under this theme, because by that time its marasmic roots had reached their limit. Victory Day had turned into a biker parade, in the middle of which two terriers drag a cart with Stalin’s portrait. All the symbols of Victory in this film go through the final stage of decomposition. Like an endless nightmare, Katyusha endlessly spins, the holiday of peace has turned into a ritual dance, summoning a new war.

Since the early 1990s, documentaries about new wars have appeared – about the Afghan, Abkhazian, Chechen wars, and the war in Georgia.3 In the 2010s, a whole series of films about the Donbas war emerged.4 These were mostly journalistic films, which unsuccessfully tried to serve as a counterweight to the national militarist rhetoric, highlighting what ‘cannot be seen on TV’ and thus serving as alternative television.

If we talk about cinema that explored military events less literally, the foundation was laid by Maundy Thursday (Chistyy chetverg, 2003) by Aleksandr Rastorguev and the much lesser-known film Life in Peace (Mirnaya zhizn’, 2004) by Antoine Cattin and Pavel Kostomarov. In both of these films, war as such is absent, yet for the first time, the theme of war against one’s own people convincingly emerges – the war between neighbors, all those wars that ultimately metonymically replace the main war: the war of the state against its people. As time went on, more and more films addressed this theme with increasing clarity: the collective film Kiev/Moscow (2015) was made, Vladlena Sandu filmed perhaps the best ‘personal’ film about the Chechen war, Holy God (Svyaty Bozhe, 2016). Other films followed, such as Milkformadness (Molokobezumiya, 2020) by Kavtaradze, in which war works not so much according to the principle of the boomerang (see Mansky’s 1987 Boomerang/Bumerang), but according to the principle of a tractor stuck in the mud, which, spinning its wheels aimlessly in the filthy mess, splashes it on everyone around. This theme has become central in the montage films of recent years.5 The war in Ukraine will mark the limit of this theme – both historically and cinematically – in the film Russians at War (Russkiye na voyne, 2024) by Anastasia Trofimova.

V. On Loznitsa

A major revelation of the early 2000s was the cinema of Sergei Loznitsa. It was in his films from this period that he accomplished what can truly be called his contribution to the history of documentary cinema. The essence of this contribution has yet to be fully understood, but it lies within the realm of what can broadly be defined as the art of observation. One might think that if there is one quality a documentary filmmaker must possess, it is an inclination to calm observation. However, documentary filmmaking in the USSR had, from its very inception, developed as a dynamic, attraction-driven, montage-heavy genre – something had to constantly be happening. The arrival of sound cinema only exacerbated this tendency, as music, interviews, and, of course, the omnipresent voice-over were added to the internal rhythm of the shot. Documentary cinema became oversaturated with text. Nothing even remotely resembling Loznitsa’s The Settlement (Poseleniye, 2001), Portrait (Portret, 2002), Landscape (Peyzazh, 2003), Factory (Fabrika, 2004), or Artel (Artel’, 2006) had ever been seen at that time. His approach contradicted not only the past but also the present of Russian documentary filmmaking, which was equally consumed by acceleration and speech. One might call Sokurov’s Spiritual Voices (Dukhovnyye golosa, 1995) a contemplative film – after all, its first thirty minutes offer nothing but a static shot of a tree line against a frozen river – if not for the fact that Sokurov’s voice continually speaks over it about Mozart and Messiaen. Rastorguev’s Motherland (Rodina, 1999) could have been a precursor to Loznitsa’s style, had he not overlaid it once again with some off-screen reading from a script. Generations of documentary filmmakers had grown up with an ingrained anxiety about a frame devoid of articulate speech, lacking textual anchoring, and the fact that Loznitsa did not share this anxiety secured him a unique place in cinematic history. His approach became liberating not only for many young documentarians of the 2010s and 2020s, but also influenced the work of his contemporaries. Hush! (Tishe!, 2003) and Svyato (2005) by Victor Kossakovsky stand in stark contrast to his 1990s films precisely because of this emancipation from the dictatorship of speech – the “inadmissibility of turning an event into text,”6 as Alexei Gusev wrote.

As for Loznitsa’s long-term influence – his impact on subsequent generations – it is undeniable. Among the many rather superficial films about contemporary Russian militarism, perhaps only Golden Buttons (Zolotye Pugovitsy, 2019) by Alexei Evstigneev stands out, bearing a clear imprint of the poetics established in Loznitsa’s Portrait and Landscape. The same influence can be seen in otherwise very different films, such as Salamanca (2015) by Sasha Kulak and Ruslan Fedorov, Summer (Leto, 2020) by Vadim Kostrov, and The Embankment (Naberezhnaya, 2021) by Nadya Zakharova. Loznitsa’s distinct radicalism has also led to his influence being felt in works that are more experimental than documentary in nature, such as Boy (2023) by Vladimir Loginov, Eight Images from the Life of Nastya Sokolova (Vosem’ kartin iz zhizni Nasti Sokolovoy, 2018) by Alina Kotova and Vladlena Sandu, Celebration (2014) and The Pool (2015) by Polina Kanis, Genrikh Ignatov’s still-life films, and Antigone (Antigona, 2023) by Elena Gutkina.

However, this trajectory has neither then nor now become the dominant one in Russian documentary filmmaking. Alongside Loznitsa’s films, another kind of cinema emerged in the early 2000s – the films of Rastorguev, Kostomarov, and Cattin – the three apostles of the documentary movement that would later be formalized in Marina Razbezhkina’s method, institutionalized in the works of her students, and popularized by the Artdocfest festival. It is this form of documentary filmmaking, where speech – if not necessarily text – is the principal object that would become the leading trend in Russian documentary cinema. And it remains so to this day.

VI. On Democratic Cinema

The cinema in question in this section is fundamentally connected to the Russian language and Russia as a territory. In some ways, its rise to prominence was indirectly facilitated by the fact that, in the early 2000s, the masters of the first post-Soviet generation were not just stepping away from the scene but also leaving the country. Frank almost stopped filming altogether and moved to Israel. Loznitsa immigrated to Germany in 2001. The following year, Kosakovsky also left Russia. However, they also fell out of the Russian film process for more formal reasons. In Loznitsa’s work, with a few exceptions, montage films began to dominate over documentary ones. Kossakovsky had always been fascinated by complex forms, and it became increasingly clear that he was more of a conceptualist than a documentarian. Even when he filmed people, he placed them within specific formal constraints: people visible through the same mirror (Svyato, 2005) or window (Hush!, 2003), people born on the same day (Wednesday 19.07.61, 1997) or in opposite corners of the world (Long Live the Antipodes!/¡Vivan las antípodas!, 2011). He quickly lost interest in the anthropocentrism of social documentary filmmaking, and the pinnacle of his career became films about water (Aquarela, 2018), pigs (Gunda, 2020), and stones (Architecton, 2024). Having plowed the field for his contemporaries, he then left it.

In this context, Pavel Kostomarov and Antoine Cattin, who had previously worked with Loznitsa, as well as Alexander Rastorguev, came to the forefront. It was they who, during those years, created films that were astonishing both in their impact and their long-term influence: Rastorguev directed Mummies (Mamochki, 2001), Mountain (Gora, 2001), Maundy Thursday (2003), and Tender’s Heat: Wild, Wild Beach (Dikiy, dikiy plyazh. Zhar nezhnykh, 2005), while Cattin and Kostomarov made Life in Peace (2004) and Mother (La mère, 2006).

Unlike Loznitsa’s films, it would be incorrect to say that their cinema appeared out of nowhere. The 1990s provided plenty of prerequisites for this kind of filmmaking to experience such an ‘explosive’ development. For instance, Tofik Shakhverdiev’s To Die of Love (1991), now largely forgotten, quietly revolutionized the portrait genre. It had already accomplished something that, even ten years later, would seem innovative – it introduced a new level of access to its subjects. For the first time, the protagonists of a documentary film were truly performing their own lives in front of the camera rather than simply responding to a director’s questions.

Kossakovsky’s The Belovs (1993), Mansky’s Grace (1995), and Dvortsevoy’s Bread Day (1998) became crucial catalysts for the near-obsessive urge among Razbezhkina’s students to film the Russian countryside. Meanwhile, Wednesday 19.07.1961 (1997) particularly clearly recorded the collective roots of this movement. These were the origins and early manifestations of what I call “democratic cinema,” a term I will elaborate on later.

Commonly perceived as a leading figure in this movement, Alexandr Rastorguev began his career as a successor to the literature-centric, auteur tradition of Soviet documentary cinema. His early films – Draft (Chernovik, 1997), Motherland (Rodina, 1999), and Your Kin (Tvoy rod, 2000) – were classical television documentaries featuring voice-over narration of poetry and literary texts. However, it was evident that Rastorguev felt uncomfortable in this genre, making these films seem like small-scale experiments. One gets the impression that he was exploring the documentary method from various angles, trying to understand where the wind was blowing from.

The answer appeared unexpectedly in the 2001 diptych Mountain and Mummies, where Rastorguev filmed the everyday lives of impoverished pregnant women. The voice-over disappeared, replaced by the direct speech of the subjects. The tone of speech also shifted – the soft-spoken, educated commentator was replaced by a chorus of hoarse, foul-mouthed voices of near-homeless people. Then came Maundy Thursday (2003) with its whirlwind of soldiers’ bodies and voices. These soldiers sleep, smoke, wash their clothes, cook food – they are harsh, exhausted, full of hatred. But above all, they speak. A soldier who speaks – such a simple concept. And yet, no one had ever seen it presented with such brutal directness, no one had ever heard it.

Rastorguev’s cinema was a direct successor to the previously mentioned “new social cinema” of the late 1980s, as it delivered the final blow to the idea of the great. Naturally, like any Soviet person, Rastorguev himself was completely and unreservedly fascinated by the concept of the ‘great’ and could not let it go so easily. His early film Draft (1997), about a pretty much unknown poet, Alexander Brunko, begins with a title card featuring a couplet by the poet and the caption: “the great Russian poet Alexander Brunko.” When Rastorguev was describing his work, he would say things like, “Every person has a great story to tell.” What he actually did was, of course, something entirely different, but the right words had not yet been found.

These words were found by Marina Razbezhkina. Today, it is clear that this was her unique mission in Russian documentary cinema. By the late 2000s, she had not only formulated a new agenda for it but had also given it something akin to institutional grounding in the form of the Documentary Film and Theater School, which she co-founded with Mikhail Ugarov. It is evident that the “Razbezhkina method” had already been practiced – and had even produced its best examples – before the method itself was formally established, that is, before she founded the school in 2009 and articulated her famous rules. This, of course, in no way diminishes the significance of her gesture – it was crucial that someone was able to articulate what was already happening so that it could finally take shape as an event. In this sense, it is clear why today, when speaking of “Razbezhkina-style” cinema, one is undoubtedly referring to something beyond just what she taught or what was created by her students. No more suitable term for this type of cinema seems to have been found, which is why I have suggested calling it “democratic cinema” – for the following reasons.

First, the main and perhaps only overarching goal of this cinema has been and remains to provide a voice and space on screen to those who have traditionally been denied one. Second, the foundation of the method used by all these filmmakers is the rejection of the authorial (authoritarian) I, the rejection which, in its extreme forms, led to the author’s virtual disappearance and the transfer of control over the filming process to the subject. Finally, nearly all films of this movement can be watched on YouTube, most of them made with zero or minimal budgets, using the simplest equipment, and intended for the widest possible audience.

The Razbezhkina method, as a theoretical framework, and the democratic cinema, as its practical manifestation, were primarily opposed to post-Soviet television journalism. The latter constructed documentary material around a predefined ‘narrative,’ supplementing it with a voice-over that explained to viewers how they should interpret what they were seeing. In a slightly different way, Razbezhkina and her colleagues also positioned themselves against the ‘non-television’ auteur documentary cinema, which had absorbed the formal techniques of Soviet fiction filmmaking and became something akin to its documentary counterpart. In this approach, the documentarian sought to ‘convey a message’ and used ordinary people instead of actors to do so. What the “democrats” found unacceptable in both cases was the instrumentalization of people on screen. Their words were filtered and selectively used; they were told what was expected of them and what was not. They were denied space to exist in front of the camera. The authorial figure loomed over the production process, creating the ‘cult of personality’ of the author, often embodied in an invisible but omnipresent voice-over.

For this reason, democratic cinema immediately began to challenge everything associated with notions of ‘greatness.’ This was not only about rejecting the expectation of greatness from oneself as an author, but also about rejecting any similar demands imposed on the subjects of the film. A telling example of this shift was Razbezhkina’s student Zosya Rodkevich’s film My Friend Boris Nemtsov (Moy drug Boris Nemtsov, 2015), which sharply marked a transformation in the biographical genre that many found intolerable. Paradoxically, the film was particularly unsettling for members of the Russian opposition, who had come to expect documentary films to present them with a polished, monumentalized image of a political figure – much like what Sokurov did in Simple Elegy (Prostaya elegiya, 1990) and An Example of Intonation (Primer intonatsii, 1991). But if the Razbezhkina method has any true originality, it is in its refusal to become ‘propaganda in reverse.’ It does not seek to uncover greatness in the ‘ordinary person.’ Simply inverting the ‘great vs. not great’ dichotomy would only reaffirm greatness on a new level – turning it into the same old claim that “those who were nothing shall become everything.” Instead, the goal was to dispel the very enchantment of ‘greatness,’ to dismantle it as a structuring phantasm. And, above all, this meant breaking free from the paralyzing phantasm that an author projects onto themselves. In this sense, if the Razbezhkina method was motivated by a rejection of “auteur cinema,” it was so in a very specific way. It was not about making films in a simpler manner or giving up excessive ambition. It was about fundamentally altering the position of the author. It was also not strictly about the author ‘not interfering’ and stepping aside – though questions of interference, its forms, and its limits were undoubtedly central to Razbezhkina’s approach.

So what was it about?

Rastorguev provided the clearest articulation of this shift in the author’s position: this was not cinema of author’s statements but of “engineering solutions.”7 What the author deliberately renounces is the position from which something is expressed. The role of the author is reduced to mastering how to work with the ways others express themselves. The search for engineering solutions must be understood precisely in this way – as the search of ways to access this expression. The formal restrictions Razbezhkina imposed on her students serve the same purpose – they limit opportunities for authorial expression: no tripods, no zooms, no direct interviews, no voice-overs, no background music. And one ‘ethical’ rule – no hidden cameras.

“We managed to become no one,” Rastorguev wrote.8 Cinema ceased to be a matter of authorial style. The protagonists were to guide and create the film. The culmination of Rastorguev’s explorations in this direction were the films I Love You (Ya tebya lyublyu, 2010), I Don’t Love You (Ya tebya ne lyublyu, 2012), It’s Been Three Years (Proshlo tri goda, 2019), and the series This Is Me (Eto ya, 2016), in which the protagonists filmed themselves. A similar logic is evident in the blending of roles between director and cinematographer in political documentary films like Winter, Go Away! (2012), The Term (2014), and Kiev/Moscow (2015). The closing credits of The Term list a dozen “directors/cinematographers.” If this cinema has a style, it could be called collective, even if a film was entirely made by a single person.

VII. On Family Values

The phenomenon from which democratic cinema emerged is the family chronicle – a video archive of family life, filmed by its own members. This process became possible only in a very specific historical period when, on the one hand, technological advancements and, on the other, the economic situation in Russia aligned in such a way that millions of families acquired portable ‘family’ video cameras. At that moment, perhaps the most democratic genre in film history was simultaneously created in millions of homes. It strictly adhered to all of Razbezhkina’s rules: no one had tripods, and those who did never cared to use them for home recordings; persuading one’s child to recite a poem on camera was the furthest this genre went in terms of interviews; there was no question of voice-over narration or background music since editing was not part of the process. And, of course, everyone knew they were being filmed – that was the whole point!

All the key films from which Razbezhkina’s method and democratic cinema grew belong, in one way or another, to the broadly understood genre of family chronicles: Wednesday 19.07.1961, Three Romances (Ya vas lyubil (Tri romansa), 2000), Svyato by Kossakovsky, Mountain, Mothers, The Heat of Tenderness (Dikiy, dikiy plyazh. Zhar nezhnykh, 2007) by Rastorguev, Together (Vdvoyëm) by Kostomarov, Mother, Life in Peace… The most obvious contribution to institutionalizing the genre was made by Vitaly Mansky, who not only founded the Artdocfest festival but also created an archive of amateur home video chronicles. In the 1990s, Mansky hosted a television program called “Family Film Chronicles” (Semeynyye kinokhroniki) and edited a film from other people’s family archives, and in 2001, he firmly transposed this genre into the political sphere with a trilogy of films about Putin, Yeltsin, and Gorbachev, whom he filmed in their homes.

The historical significance of family chronicles cannot be reduced to their ‘sentimental value.’ For those born in the 1980s and 1990s (Razbezhkina’s students), this genre had a much more concrete meaning. It literally supplied them with moving images of their childhood, serving as a crucial support for their often-vague memories of this important period. In a way, the form of family chronicles played a role in shaping the subjectivity of entire generations. It is no surprise that when the principles inherent in this form resurfaced as a kind of artistic manifesto proposed by Razbezhkina, it sparked an explosive interest. Essentially, Razbezhkina proposed something like the concept of an ‘extended family’ taken to its extreme – she encouraged young filmmakers to perceive any environment they wished to immerse themselves in as an extension of their family, to use their cameras as if they were ‘family’ cameras, and to take on the ambitious task of filming complete strangers as intimately as they would their own children. To achieve this, they had to abandon conventional notions of tact and etiquette typical of interactions between strangers and instead establish more direct and unceremonious relationships during filming – akin to family relationships. “You can’t afford to be a good person,” Zosya Rodkevich said about this approach.9 In the same interview, she gives an interesting definition of “directing” in documentary cinema: “You show the subject that they can’t get away from you and that you won’t leave them either – so that’s it, now you’re always following them with the camera, and they simply have no chance to escape from you.” It is clear that what she describes is precisely familial-type relationships.

The first application of this method in the films mentioned above was literal – directors filmed other people’s families as if they were their own, and strangers as if they were their relatives. Family chronicles gained a new status – they were recreated as an artistic form. This resulted in films such as Temporary Children (Vremennyye deti, 2010) and White Mama (Belaya mama, 2018) by Zosya Rodkevich, Together (2008) by Pavel Kostomarov, September, 25 (25 sentyabrya, 2010) by Askold Kurov, I Love You (2010) and I Don’t Love You (2012) by Aleksandr Rastorguev, Milana (2011) and Come On, Scumbags! (Eshche chutok, mrazi!, 2013) by Madina Mustafina, Diana (2012) by Vladlena Sandu, Anton Is Right Here (Anton tut ryadom, 2012) by Lyubov Arkus, Zviszhi (2014) by Olga Privolnova, Not My Job (Chuzhaya rabota, 2015) by Denis Shabaev, A New Happy Life Will Begin Soon (Skoro nachnetsya novaya schastlivaya zhizn’, 2015) and Chronicles of a Revolution that Didn’t Happen (2016) by Konstantin Selin, Songs for Kit (Pesni dlya Kita, 2017) by Ruslan Fedotov, Braguino (2017) by Clément Cogitore, It’s Been Three Years (2019) by Rastorguev, My Love (Zhanym, 2018) and Jubilee Year (Yubileynyy god, 2019) by Zaka Abdrakhmanova, Hey, Bro (Khey, bro!, 2019) by Alexander Elkan, Kind Souls (Dobryye dushi, 2019) by Nikita Efimov, A Boy (Mal’chik, 2020) by Vitaly Akimov, R2CC (2020) by Masha Chernaya, The Russian Way (Russkiy put’, 2021) by Tatyana Soboleva, Holidays (Jours de fêtes, 2022) by Antoine Cattin, Silent Sun of Russia (2023) by Sybilla Tuxen, Edge (Kray, 2022) and Brave New World (Divnyy mir, 2023) by Ivan Vlasov – and this is far from an exhaustive list. Naturally, the concept of an ‘extended family’ also had less literal applications, serving as the reverse side of the long-standing 20th-century critique of the family as the first institution that introduces a person to the world of institutions. As a result, filming various institutions became a crucial part of this cinema: prisons,10 housing and utilities services,11 museums,12 schools,13 a cadet school,14 psychiatric hospitals,15 factories,16 and COVID hospitals.17

In recent years, this cinema has been undergoing clear transformations. I think it is safe to say that the poetics of democratic cinema, after fifteen years of continuously ‘pouring out’ from video cameras across the country, is gradually starting to fade. The changes occurring now, I would divide into three categories.

VIII. Three Steps Into the Future

First, the construction of the ‘image’ is clearly making a comeback. A ‘pretty image’ (kartinka in Russian) was something Rastorguev despised. In a film about him, there’s a scene where he gets furious over the fact that Alexei German spent ten years squandering budget funds to meticulously construct the ‘pretty image’ of his film Hard to Be a God (Trudno byt’ bogom, 2013). In today’s documentary films, which are now coming to the forefront, the ‘image’ – meaning the work on framing, color, composition, and so on – has returned to center stage. In addition to the previously mentioned Boy by Akimov, Eight Images from the Life of Nastya Sokolova by Sandu, Summer by Kostrov, and Golden Buttons by Evstigneev, we can highlight the works of Sasha Kulak and Ruslan Fedotov, as well as the widely discussed Where Are We Headed (Kuda my edem?, 2021) by Ruslan Fedotov, Tamerlan’s Love (Lyubov’ Tamerlana, 2015) by Sandu, The Wolf and the Seven Kids (Volk i semero kozlyat, 2017) by Elena Gutkina and Genrikh Ignatov, Immortal (Surematu, 2019) by Ksenia Okhapkina, Haulout (Vykhod, 2022) by Maxim Arbugaev and Evgenia Arbugaeva, Alive (Zhivoy, 2022) by Konstantin Selin, Wind Has No Tail (U vetra net khvosta, 2024) by Ivan Vlasov and Nikita Stashkevich, and Shards (Oskolky, 2024) by Masha Chernaya. The peak of this trend in documentary filmmaking is seen in the experimental works of Alexandra Karelina, Nastia Korkia, Dina Karaman, Daria Likhaya, Elena Gutkina, Genrikh Ignatov, Artem Terentyev, Vlada Milovskaya, Mukhammed Aldridi, and the “Luch” film collective.

Second, we are increasingly seeing a world in front of the camera that is closed off to the filmmaker – a world of human backs. Where Are We Headed marks an important shift in this regard: the filmmaker distances themselves from their subjects, does not establish any relationship with them, and does not necessarily even inform them that they are being filmed. While filming My Imprisonment (Moyë zaklyucheniye) in a psychiatric hospital where she had been admitted, Faina Muzyka carefully hid her cameras from the staff. Both of these examples represent a step away from the dialogical method. In this sense, the world captured by Fedotov, Muzyka, and others becomes the opposite of the familial world – not because it is aggressive or hostile, but because it remains foreign. Either it is a world that refuses entry and can only be observed from the outside, or it is a world the filmmaker themselves rejects, refusing to engage in dialogue with it. Both of these positions are structurally incompatible with the inherently dialogical method of Razbezhkina.

Third, we see the return of the author – not only in the form of an authorial statement or distinctive style but more directly, as the protagonist of their own film. Despite a few significant exceptions (Denis Shabaev’s 2014 Together/Razom and Arina Adju’s 2016 All Roads Lead to Afrin/Vse dorogi vedut v Afrin), democratic cinema as a whole avoided placing the filmmaker in the frame. It was inspired by a kind of mission of ‘going to the people’ with a camera (Razbezhkina herself described the origins of her method in these terms – she abandoned her library books, got up, and walked into the taiga). Filmmakers were taught not to focus on themselves, but to turn outward toward the surrounding world. The goal was not to express ideas, but to document reality and thereby save it from oblivion. Rastorguev even explicitly called this a mission of “saving humanity.” It is not surprising that today, when so much is documented and so little is saved, young filmmakers are searching for new approaches. This is reflected in the aforementioned films by Faina Muzyka and Dasha Likhaya, Holy God (2016) by Vladlena Sandu, The Light That Watches Me, While I Watch the North (2022) by Vlada Milovskaya and Knjazhna, How to Save a Dead Friend (2023) by Marusya Syroechkovskaya, Shards (2024) by Masha Chernaia, and With My Open Lungs (Mit meinen offenen Lungen, 2024) by Yana Sad. Notably, this process has coincided with the gradual disappearance of the family chronicle from modern family life. The camera no longer exists as a separate object shared among family members. It has become part of a hybrid personal device – the smartphone – and family chronicles have been replaced by personal archives and social media documentation. This shift may partly explain why democratic cinema is gradually losing its appeal while one of its variations – personal documentary filmmaking – is gaining strength.

- Sandomirskaya, I. (2012). From August to August: Documentary cinema as an archive of stolen revolutions [Article in Russian]. New Literary Observer, (5). https://magazines.gorky.media/nlo/2012/5/ot-avgusta-k-avgustu-dokumentalnoe-kino-kak-arhiv-pohishhennyh-revolyuczij.html ↩︎

- Sandomirskaya (2012). Translation by the author of this article. ↩︎

- See Cursed and Forgotten (Proklyaty i zabyty, 1997) by Sergei Govorukhin, Collecting Shadows (Sobirateli teney, 2006) by Maria Kravchenko, and Russian Lessons (Uroki russkogo, 2009) by Olga Konskaya and Andrei Nekrasov. ↩︎

- A House on the Edge (Khata s krayu, 2016) by Yulia Vishnevets, Donbass Airport (Aeroport Donetsk, 2015) by Andrei Erastov and Shahida Tulaganova. ↩︎

- Manifesto (2022) by Angie Vinchito, Boy (2023) by Vladimir Loginov, and Two Hundredths (Dvukhsotyye, 2024) by Konstantin Seliverstov. ↩︎

- Gusev, A. (2009, July 13). Ecce cinema [Article in Russian]. Seance. https://seance.ru/articles/ecce-cinema/ ↩︎

- From the archive – Aleksandr Rastorguev on “engineering” cinema [Article in Russian]. (2020, April 17). Seance. https://seance.ru/articles/aleksandr-rastorguev-arhivnaya-zapis/. Translation by the author of this article. ↩︎

- Rastorguev, A. (2020). Kinoproby [Article in Russian]. Chapaev Media. https://chapaev.media/articles/9485. Translation by the author of this article. ↩︎

- Nastoyashcheye Vremya. Dok. (2020, January 17). How to become friends with a famous opposition leader: An interview with Zosya Rodkevich [Video in Russian]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/MmyKQasgfDc. Translation by the author of this article. ↩︎

- Strict Regime (Nachal’nik otryada, 2021) by Nikita Efimov and The Dream #9-2380 (IK-6) (Son №9-2380 (IK-6), 2022) by Lidia Rikker. ↩︎

- Slava Fedorov’s trilogy. ↩︎

- Leninland (2013) by Askold Kurov and Dramatic and Mild (Rezkiy i myagkiy, 2018) and GES-2 (2021) by Nastya Korkia. ↩︎

- Hey! Teachers! (Katya i Vasya idut v shkolu, 2020) by Yulia Vishnevets and Mister Nobody vs. Putin (2025) by David Borenstein and Pavel Talankin. ↩︎

- Golden Buttons (Zolotyye pugovitsy, 2019) by Alexey Evstigneev. ↩︎

- Monologue (Monolog, 2017) by Otto Lakoba and My Imprisonment (2023) by Faina Muzyka. ↩︎

- The Last Limousine (Posledniy limuzin, 2014) by Darya Khlestkina. ↩︎

- The Third Wave (Tret’ya volna, 2021) by Konstantin Selin. ↩︎

Leave a Comment