On the Art of Dusting Without Using Detergent

Renata Lučić’s A Year of Endless Days (Godina prođe, dan nikako, 2024)

Vol. 145 (May 2024) by Lucian Tion

There is a scene in the middle of Renata Lučić’s documentary A Year of Endless Days in which she and her father are having an argument. Despite her father’s insistence that the best way to clean furniture is to sweep its surface with a dry feather duster, his daughter, who is both the protagonist and director of the film, argues that this outdated practice is wrong and that a cloth dipped in water and detergent is required to properly clean surfaces. She argues that otherwise, dust would simply rise in the air and then settle back on the furniture.

Insignificant? Comical? No, because we are in rural Eastern Europe, where a vast majority of middle-aged residents left behind by adult children who have moved to the West regrettably spend their days arguing over minute details that have little bearing on their existence. In her film, Lučić returns from Austria, where she and her mom had emigrated, only to find her father and his best friend (whose wife also left him) stuck in a monotonous limbo consisting of cooking, cleaning, and performing repetitive household chores. If apparently insignificant, the exchanges between Renata and her father, which run like a red thread through her film, offer an insight into his desolation and loneliness. While respectful of these for a while, Renata clashes with him over the proper way to dust furniture, and, in a sudden bout of irritation, she accuses her father of having an obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The diagnosis doesn’t agree with her father’s strong personality type, which causes disagreement between them. This reveals not only the rifts in their family but the larger emotional conflict between generations occurring in the director’s native Croatia and between parents and children all over Eastern Europe as well. Schooled in the West, where many children had already started families, the offspring of postsocialist-era parents return to their native lands to find their relatives fixated upon patterns and behaviors, such as the allegedly incorrect way to dust furniture, that sometimes make them cringe.

The representation of such conflicts isn’t new. They have been used ad nauseam in New Romanian Cinema fiction films. For instance, Răzvan Rădulescu and Melissa de Raaf looked in depth at the conflict between an adult daughter, married in the Netherlands, and her mother in Bucharest in First of All, Felicia. When, after a prolonged absence, the daughter returns to visit her parents, accusations of poor parenting techniques begin to arise with a vengeance.

What keeps Renata’s film from going in that direction is that, with the exception of the brief OCD episode, she grumblingly accepts her father’s behavior without trying to change him. For that reason, the film is not strictly about conflict (which would have probably made for a juicer film) and more about the things that remain unsaid once both parents and children accept the fact that different paths in life turned them into, quite simply, different human beings. This leaves the documentary room to focus on absences, those of Renata’s mother from her father’s life, but also those of the villagers, who try to find more lucrative employment in the West, from their native land.

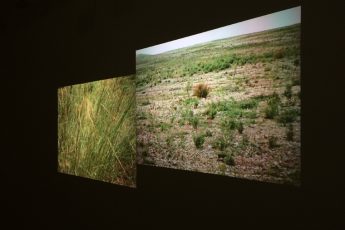

Only that Renata’s emotional investigation stops here because the director finds it difficult to navigate the waters of absence without turning repetitive. As Gene Hackman famously remarked in The French Connection about a Rohmer film which made him feel as though he was “watching paint dry,” a documentary about absence can be expected to move at a slow pace. While Renata’s film narrowly escapes that fate, her portrayal of trauma is only partially successful, due to the notorious difficulty of depicting emotional suffering in documentary film. For this reason, even though the director conveys the psychological trauma of her family undergoing a painful separation (the last time the whole family was seen together was around a bountiful Christmas table in the 1990s, a VHS-captured moment which both opens and closes the film), the melancholy and pessimism come less from the characters and more via the portrayal of bleak exteriors, which are mostly captured under a gray sky. Symbolical as these shots may be, they do not replace the much-needed human touch Renata has difficulty communicating. The final bike ride she and her father take amid the stunning but empty scenery of Slavonia is insufficient to make up for the loss in communication, even though this loss may very well describe their relationship. As the sun sets, the village seems warmer, indeed, but the inhabitants’ lives, as Renata’s father laments, do not seem any less bleak. Although the movie finishes symbolically, like dust particles drying in a detergent bubble and leaving only faint traces on the furniture, metaphors fall short of expressing unbearable suffering.

What the film manages to portray very well, on the other hand, is the enormous disparity between the haves of the West and the have-nots of the East in this still divided continent. As Renata Lučić unequivocally confirms in her film, Eastern Europe is still significantly impacted by what Czech journalist Saša Uhlová referred to in her investigative documentary Limits of Europe (2024) as a “wage curtain”, which strangely replaced the previous Iron Curtain. In this (dis)guise, the continent is politically, yet not economically united. After the abuse her mother endured alongside her husband, which Renata subtly alludes to, the marginalized social classes that comprise the majority of migrant workers taking menial jobs in the West – the mother is frequently depicted in old photos farming asparagus, a vegetable that until recently had not even been introduced to Eastern Europe – continue to bear the brunt of exploitation.

Furthermore, the docu pushes some notable boundaries. First, it explores the rare domain and sensitive issue of bankrupt masculinity, a status of masculinity we infer is reached once toxic masculinity goes bad. The father’s portrayal as a former macho man who has gone from commanding over land and family (he is a forest ranger, no less) to spending his days in the company of a friend cooking fish is touching. Moreover, Renata portrays her father without judging him, presenting him warts and all for the camera, which shines some suggestive light on both his positive and his dark sides, as it were. This enables us to see why dedicating oneself to mundane tasks such as dusting, cooking, or fixing things (OCD traits notwithstanding) helps people survive the loneliness, depression, and malaise that gripped them and their country since the 1990s.

This portrayal of silent desperation is sincere and heart-warming and differs from the previous guises in which generational conflict has been depicted in Eastern European documentary cinema. In both Mila Turajlić’s The Other Side of Everything (2017) and Bojina Panayotova’s I See Red People (2018), for example, the directors mount an attack on their parents for ideological reasons, namely because they were once supporters and activists in the Communist Party. Both Turajlić in Serbia and Panayotova in Bulgaria conflate their parents’ past with that of their respective countries, concluding that both of these were directly responsible for their unhappiness. The problem with these forerunners’ discourse is that it is judgmental, anachronistic, and that it scapegoats Communism without looking in depth at the personal and psychological context surrounding strained relationships between traditionalist parents and emancipated adult children. In other words, this discourse betrays a certain entitlement on the part of the children. Although numerous young Eastern European directors once subscribed to this condemnatory yet uncritical trend, which lasted a good decade into the early 2020s, films like Lučić’s signify that this tendency is coming to an end. This would further mean that more mature Eastern European directors are now prepared to take the stage and discuss their and their countries’ past with more honest, less unilateral voices, addressing the complexity that each of their personal cases entails.

Leave a Comment