Making a Mark

Urszula Morga and Bartosz Mikołajczyk’s Signs of Mr. Plum (Znaki Pana Śliwki, 2025)

Vol. 161 (January 2026) by Zoe Aiano

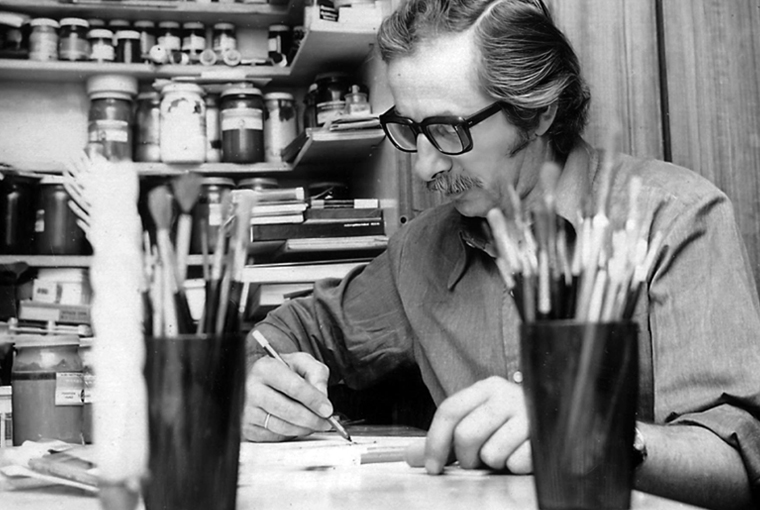

Graphic designers have yet to become a staple of biopics, either fiction or documentary. This makes a lot of sense, given that, despite it being one of the creative professions that is most present in daily life, the work is still largely anonymized, and indeed any recognizable identity is supposed to be attributed to the client company and not to the creator. Upsetting these premises, Karol Śliwka earns his place as the eponymous protagonist of Signs of Mr. Plum by Urszula Morga and Bartosz Mikołajczyk not only because his vast legacy of work is undeniably iconic, but also because he lived a life worthy of a folk tale.

The documentary is structured around an in-depth interview with Śliwka in which he recounts his own life story. Curiously, Śliwka died in 2018, so seven years before the release of the film, but no further context for this interview is provided, leaving audiences to speculate on the reasons for this time lapse (which is most likely attributable to the never-ending obstacles inherent to independent filmmaking but is still slightly jarring in its lack of explanation). Accompanying this central narrative is a large array of home videos shot by Śliwka and his family members, providing an insight into his personal life and especially his family relations. Perhaps most endearingly, it reveals how a man who dedicated his entire life to highly refined aesthetics as a form of expression was also unable to resist the call of trashy Hi-8 filters and cheesy camera fonts. The third type of visual materials is archival footage – some being of his many achievements but others just generally showing the period being discussed, seemingly serving primarily as filler and/or vibes. Of course, his many designs also feature prominently, often in the form of snappy montages, which fits the overall pop style but doesn’t leave a lot of time for actually being able to appreciate them.

The dramaturgy of Śliwka’s biography jumps between chronologies, starting, logically enough, with his most internationally recognizable success winning design competitions for UNESCO with a characteristic dove of peace, framing him not only as a person of note but also as a presumed pacifist. It then goes on to tell the rest of his personal history thematically, an approach that can sometimes be a bit disorienting but makes sense overall. A prime example of this is the story of how he lost his eye as a boy while sweeping for landmines at the end of World War Two. This event is mentioned very late in the running time, when Śliwka’s prowess and personality have already been long established, thereby mitigating the possibility of audiences focusing on his physical impairment rather than his talent.

The tone of the film, in keeping with that of its central figure, is characterized by a wry humor combined with a matter-of-fact storytelling style that sometimes juxtaposes with, and thereby heightens, the incredible events being recounted. Another attribute common to both is a lack of critical reflection. Śliwka certainly does not concern himself with modesty, false or real, and he glibly recalls limiting the number of entries he would send into competitions to avoid the awkwardness of winning all of the prizes. He was clearly not only gifted but also passionate and extremely hard-working, but there is only a very superficial consideration of whether his workaholism was actually a positive attribute, except in small moments where he concedes how little he was around for his family. Similarly, Śliwka talks about how his wife gave up her career as an opera singer to support him, an act that is unproblematically presented as appropriate and even romantic.

Given that the majority of the film is concerned with Poland’s Communist period, and that most of Śliwka’s work was created in this context and sometimes for Communist organizations, politics is mentioned surprisingly briefly. There’s an anecdote about Śliwka accidentally criticizing the Soviet Union to a government official, and when discussing the capitalist era he talks of “good democracy” while also critiquing the new way of doing business. While depictions of Eastern Europe are often too concerned with dissecting people’s ideological convictions and actions, in this case it does feel like a kind of conspicuous absence. This may not be a flaw on the part of the filmmakers but perhaps more a reflection of the protagonist’s worldview. Karol Śliwka comes across as a very twentieth-century genius, a man so consumed by his own artistic output that wider community constructs such as government and family are of little concern beyond the issue of whether they facilitate or hinder his career.

Signs of Mr. Plum is playful, catchy, and watchable, truly an impressive feat for a topic that could so easily be dismissed as boring, and in this sense, it succeeds in restoring a certain credibility to graphic design as a legitimate artform with legitimate artists. It presents the artist in question as an endearing curmudgeon whose greatness excuses any foibles, yet it feels like it could have gone further in its examination of both Śliwka as a character and especially his work, doing greater justice to both by allowing for more complexity and nuance.

Leave a Comment