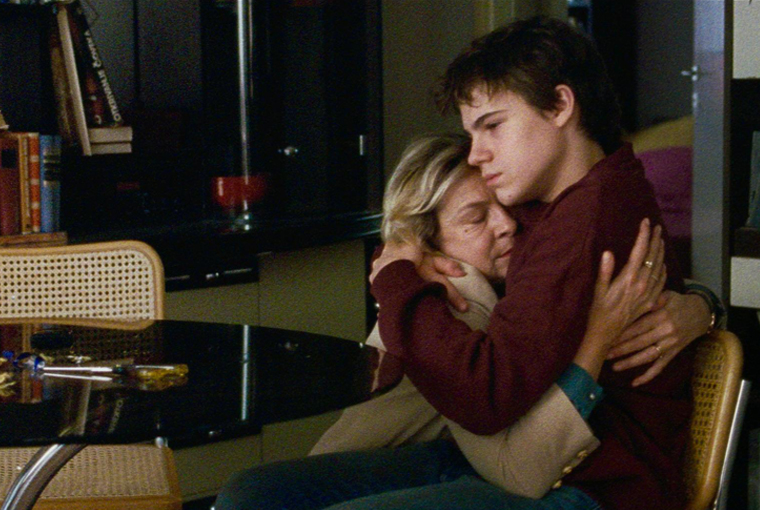

The year is 1996. Rallies in Milošević’s Serbia. The country that is truly lost is the one obliterated in what already seems a lifetime ago, at the nucleus of a disassembling unity of countries and sentiments, alongside other placemats, name-holders, and objects that had once constituted its core. And had Vladimir Perišić’s Lost Country focused on this material loss, the film might have seemed more centered within the parameters of the real. But the symbolic loss Lost Country ultimately deals with sets a different requirement: a coming-of-age precipice for the young protagonist Stefan. During the timespan of his formative years, the film discusses how big of a gap lies between our illusions and the convictions we can bear, and how we align ourselves with what is eventually handed to us. The disillusionment of the early teens is hard enough as it is; having a mother representing a political party whose leaders everyone you know seems to be labeling as fascists and crooks adds an insufferable layer to the process. Unfortunately, in this aspect, the base idea does not transcend its own range – and because of its convoluted form, the singular does not cross over to the universal.

Colors of cavernous shades dominate Perišić’s feature – his second film in total, although it is the first he has made in fifteen years. Within the film’s bleak aesthetics, this translates into a puddle of opportunity, a sullen yet hopeful horizon. The film’s prudently chosen color palette supports an open field of vision; a simultaneous creation of a wormhole birthing endless (re)productions of situations and characters, (re)created once again – in vain. And as is often the case with reiterations of history, scenes and sequences unfold within the formal logic of the film’s momentum, yet offer no space for redemption. This, perhaps, is one of the reasons why the film seems nimble, in spite of its steady dominant form gradually shifting towards a lower level than what must have been intended. Through its acute attempts to offer an overview of a country and its people with no exit strategy, the film locks itself within a scope where the fabric of the same color reigns. Unfortunately, this semi-meta level does not bring liberation or introduce a new discourse, nor does it create a new narrative.

In order to truly come full circle, we have to begin from the end: the final proof of the circular structure lies in the film’s very last scene, its close – a Bressonian attempt at an impactful resolution that unfolds with no insight. We’re left staring into the dark, but there is nothing returning the gaze from within the void. Perišić displaces the center, its inner and outer linings. This is where the film stops, and the fable begins, with all of its intricate weaving. In his efforts to bring forth the unadulterated truth, Perišić’s hasty (or indolent) leanings upon the obsolete French cinematic machinery make him abandon his only noteworthy hypothesis. And so the utmost issue of the film seems to be its fabricated delivery, an attempt at naturalism sung, paradoxically, at such high notes that it inescapably becomes reduced to a story, devoid of meaning, of any substance. Cinema would have been the truth, but a story is a lie.1

Notes on the Cinematography

Setting aside the unwavering aesthetics that French cinema has selectively been displaying for decades – if we are to translate the cinematic language in stylistic terminology –, the film’s form serves its content well. Starting off in rural Serbia, just outside Belgrade, we follow Stefan’s journey. Here, at the very beginning, the visuals reach out for the poetry of the mundane: apple picking, a dog running about, reminiscence about the state of affairs at the time that grandmother and grandfather were still young. The time spent in nature adds a pictorial, almost pastoral quality to the narrative. The film heavily draws upon the pastoral trope, setting it forth as the most organic aspect of the film’s whereabouts. The environment shapes the sidelined characters; much like the allocation of the film in the particular place and time. The film is in reality as much as in figurative speech tied up in its own creation to space-time. However, Perišić doesn’t push this parallel metaphor a lot further. The most he does is juxtapose it with the coldness of the cityscape, the banality of its visual and allegorical binary opposition.

The camerawork in itself assumes a stationary slant, solid in its consistency – a silent witness subtle in its own presence, without an elaborate separate life of its own. The film employs a singular format from the start – this visual aspect remains static throughout, seemingly immobilized. The camera is almost deemed too frightened to come closer and approach the protagonists. By remaining far-flung, the camera’s standpoint does open up a bit more depth of field, allowing the audience’s gaze access to the things that are seemingly positioned further apart. But its orifice is in equal part its downfall – once our glance starts to linger around the aperture, we start to spot the feeble structure. It also makes it quite easy to circle back to the precursory issue of the weak content of the script – in spite of the immensity of the emotional bind that the film underlines by constantly returning to the trauma: having a parent who will never put you first. And unfortunately, it is the formal element of pure cinematic value that cannot solely be masked through visual compensation.

The Trouble With Language

Perišić’s directing is lukewarm at best, almost annoying in its perseverance to pursue the essence of his looming characters’ state-of-being. The film’s editing is stereotypically French; the dialogs are hardly believable to be the banter of 15-year-old boys even if the unruly utterances are plucked sideways, rushed in from the surrounding adulthood attempting to break away, whether it’s to make space for courage or for amorality. There is no gateway for this introduction: the language structure of these sentences seems to be so disjointed that its uncanny aftermath leaves the spectator entirely thrown out of the film’s stream of consciousness. Once again, the impression is forced upon us that it’s not a film; it’s a story being told.

The ending itself, as Bressonian as the rest of the film aspires to be, does not work in the film’s favor even when drawn out as a direct reference to one of the giants of French cinema. Rather, like much else in this shaky work, it brings about a sense of incredibility. By placing it as the (factual) denouement of the final sequence of the film, we’ve come full circle through the incredulous country we’re not even sure exists, and its conformist characters do not afford us rest, neither for us, nor for themselves. Scratching just under the surface, there is a profound lack of depth to the way these protagonists are written. Lethargy and motionlessness become character traits – an attempt to portray the general aura of the time at hand. As do their vocalized battles filled with feigned tiredness and indifference rather than hunger for justice. In a sequence where his friend’s mother tries to expel Stefan from her house in an episode filled with warranted rage, her righteous anger propelled by motherly instinct seems counterfeit. And it is not her emotion that’s feigned (or the actress’ performance for that matter) – it’s the use of language that deems it thus easily expendable. Rancière wrote about how2

it [cinema] discards the “fable” in the Aristotelian sense: the arrangement of necessary and verisimilar actions that lead the characters from fortune to misfortune, or vice versa, through the careful construction of the intrigue […] and denouement. The tragic poem, indeed the very idea of artistic expression, had always been defined by just such a logic of ordered actions.

The structure of the narrative logic is ordained by the undisturbed flow of time inasmuch as it unfolds entirely separately from it. This may well be an idiosyncrasy attributed to all detached periods of human history, during all of which we’ve known exactly what we were (not) doing.

Time in Stasis

In many ways, Perišić’s film manifests itself as temporal – not merely as a linear progression, but also in the sense of its deeply entwined encompassment of both personal perception and collective experience. Bergson, who wrote extensively on the notion of lived time, which he also called ‘real duration’ (durée réelle), points out that the way lived time separates itself from the notion of ‘mechanistic’ or scientific time is precisely its relation to space. Lived time is not predetermined by superimposing space onto it, is not constructed by separate chunks which are then glued together – which may be analogous to how we think about space, or paradoxically, about film.3 Lived time manages to creep into Perišić’s film not merely by a showcase of a linear progression, but also through a deeply entwined encompassment of both personal perception and collective experience. And as such, it deserves the highest of compliments. Yet, much like the opening that leads the eye through the film’s leaden landscape, this unambiguous time remains motionless. Similar to any valid act of reiteration, death will do it, it will always suffice. And here we are, back at the close: once fragmented and dispersed by the protagonists’ thoughts, actions and fears, death can only take the shape of the ever-coming. As a result, all that it touches remains static, perhaps precisely in its anticipation. Paralyzed by fear, whether that be the fear of disillusionment or its coming consequence, Perišić’s young protagonist assumes a plastic, automatic role, rendering all further film movement impossible.

On a conceptual level, a static film is nothing inherently unfortunate, yet this conceptual flair has no way of penetrating the ensuing layers without unequivocally carrying within itself the notion of the mechanical. In this sense too, the film is reminiscent of the automatism of Bressonian characters, however naturalistic they might seem to us in their own pitiful woes. In addition, and interestingly enough, the film shares a common ground with another 2023 title, The Beast by Bertrand Bonello. And while perhaps closer to the rudimentary idea of Henry James’ original work (the 1903 novella The Beast in the Jungle) than to Bonello’s adaptation in its slow-roasting, silent lament on what’s to come and what’s to be done about the things nothing can be done about,4 the two works of art differ in medium but regain (again and again) the same structure of sullen premonition of the inevitable, yet barely substantial – that which is always already there. Or, in layman’s terms, the notions of anticipation and paralysis.

References

- 1.Rancière, J. (2006). Film fables. Berg Publishers; 1.

- 2.Rancière, 2006, 1–2.

- 3.Phipps, J.-F. (2004). Henri Bergson and the philosophy of time. Palgrave Macmillan.

- 4.When attempting to describe this feeling, James writes: “[…] a perception so sharp that nothing else in the picture comparatively lived’’ (James, H. (1993). The beast in the jungle and other stories. Dover Publications; 69).

Leave a Comment