Epileptic Seismograph

Franciszka and Stefan Themerson’s Europa (1931)

Vol. 118 (October 2021) by Isabel Jacobs

I can’t / I don’t want to express it in words !

– Anatol Stern, “Europa”, 1929.1

For eighty years, Polish filmmakers Franciszka and Stefan Themerson’s avant-garde short Europa (1931) was believed to be lost. After the spectacular rediscovery in the German Federal Archives in Berlin, the restored 12-minute anti-fascist short celebrated its world premiere at the 65th BFI London Film Festival 2021. Featuring a newly commissioned soundtrack by Dutch composer Lodewjik Muns, Europa is one of the most important rediscoveries in recent film history.

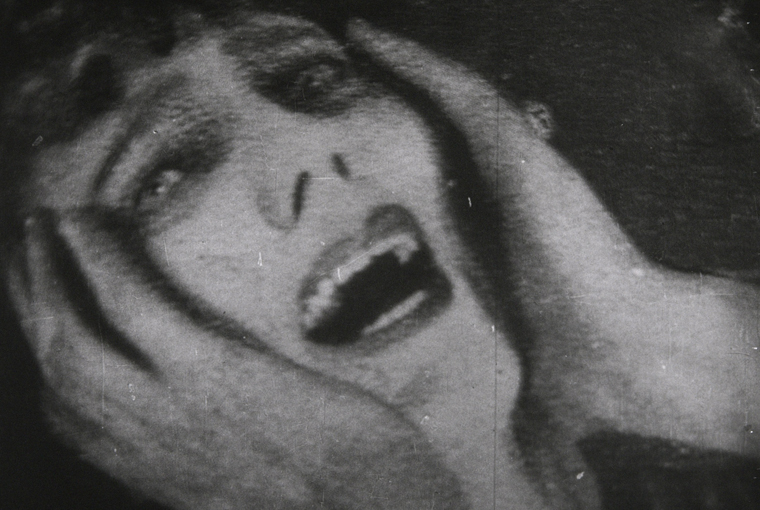

In swift cuts, fleeting shots of plants are superimposed on fragments of every-day life. Jellyfish, a typewriter, gas masks, a piano, marching legs, a pipe, bread, faces, a guitar, abstract shapes, a boxer, and Christ merge into a Surrealist tableau in black-and-white. The jerky camera moves up a trouser leg. In another shot bizarrely corresponding with the trouser shot, we see a tree trunk rising to the sky. One returning motif is a pounding heart. In a dreamlike stream of images, Europa masterfully interweaves horror with humor. The absurdities and alienations of modern city life meet visions of a posthuman reality, overtaken by natural forces.

After they met in Warsaw in 1929, the Themersons began their lifelong collaboration on experimental films, children’s books, and illustrations. Both the short The Pharmacy (Apteka, 1930) and their second film Europa (1931) were produced in the couple’s bedroom. (Europa was shot with a borrowed camera, cut on the kitchen table, and produced without any money.) One of Europa’s most iconic scenes, the time lapse of a grass stem gradually demolishing some paving stones, was arranged and photographed daily in their home. The result of the home-built experiment is a powerful moving image of nature’s revenge against civilization.

Loosely based on Polish poet Anatol Stern’s futurist 1925 poem “Europa”, the Themersons’ film fuses collages with photograms and unconventional shots. It is believed to be the first significant avant-garde film from Poland. Back then, for want of any existing genre depiction, a Polish critic appraisingly called Europa the first “film-poem”. For contemporary audiences, the Themersons’ film must have been a shock. Parts of its provocative imagery, including shots of nudes, were taken out by officials.

Excessively using experimental techniques, Europa ranks among other famous works from the period, such as Hans Richter’s Ghosts Before Breakfast (Vormittagsspuk, 1927) or Man Ray’s The Starfish (L’étoile de mer, 1928). And yet, Europa has a very unique feel to it. Unlike, for instance, Soviet montage films, the Themersons cast a dark shadow on acceleration, capitalism, and technology. Their view on human civilization is bleak and dystopian. A modernist apocalypse, Europa portrays a world in rapid decline. Juxtaposed images of war, ecological disaster and the menacing rise of fascism culminate in a visual cacophony. Europa does not convey much hope for a bright future of mankind. And yet, there is a subtle beauty, evoked by the cosmic images of natural elements such as plants, leaves and the sky.

The narrative follows Stern’s poem, recreating its evocative motifs and sceneries. From several odd angles, at times in close-ups on his mouth, we see a man eating. Apples are cut. Film rolls are cut. A typewriter feverishly spits out propaganda. Fingers hack at a piano. Legs march. Newspapers are stuffed in someone’s mouth. Man is transformed into an eating-machine. Or, in Stern’s delirious words:

they feed us / they feed us / they pour down our throats / food for the spirit ! / 500 metres of trichinae of / sermons / faded tapeworms of / newspapers / sweet / virulent / bacilli of words / are shoved into our mugs / by the gluttonous fraternity of / scribblers of / presidents of / ministers of education / china of the west ! ! / stop poisoning us / we are not rats !

After Europa, the Themersons worked on several other experimental films, including Musical Moment (Drobiazg Melodyjny, 1933 [lost]), Short Circuit (Zwarcie, 1935 [lost]), a commissioned work about the dangers of electricity, and Adventure of a Good Citizen (Przygoda Człowieka Poczciwego, 1937).

Emigrating to France in 1938, the couple stored one copy of each film at the Vitfer film laboratory in Paris. Franciszka begins working for the Polish Government in Exile as a cartographer. After the outbreak of the Second World War, their films were seized from the lab by the Nazis in 1940. Since then, Europa was believed to have been destroyed.

The Themersons moved on to London where they produced two films, Calling Mr Smith (1943), an anti-war film, and The Eye and the Ear (1944/45), in which they explored ways of visualizing music. Franciszka co-founds the experimental publishing house and artists’ club Gaberbocchus Press with her husband. In 1983/84, the Themersons tried to reconstruct Europa from surviving stills. A few years later, Polish filmmaker Piotr Zarębski produced his own reimagination in homage to the Themersons. The two films were also shown at Europa’s 2021 premiere, as documents of its powerful afterlife in the artists’ memory.

In 1988, both Franciszka and Stefan died, convinced that Europa had not survived. And yet, Europa’s story does not end here. In 2019, their niece and heir, Polish-born British art critic Jasia Reichardt, hears through the Pilecki Institute that a copy of Europa might have survived. With the help of the Commission for Looted Art in Europe, the original 35mm nitrate film was retrieved in the German Federal Archives in Berlin. It is a miracle that Europa survived its odyssey. After its seizure from the lab in Paris, it was kept in the National Socialist Reichsfilmarchiv. In 1945, Soviet authorities transferred the Nazi archive to Moscow. In the 1950s, the film was “returned” to the East German State Film Archive, now part of the Bundesarchiv.

For almost a century, Europa has been a missing piece in avant-garde history. However, as its world premiere at the BFI showed, it never ceased to haunt the imagination of Polish filmmakers such as Zarębski. While early European avant-garde film is still mostly associated with France, Germany and the Soviet Union, Europa reminds the viewer of the rich cultural landscape of Poland in the interwar period. The Themersons transmit a daunting, highly timely vision of Europe under the spell of ideological fragmentation. Not least thanks to Muns’ extraordinary score, Europa can finally be seen again – through new eyes and ears. And with it, the visionary spirit of the Polish avant-garde rises from the dead. As Stern puts it:

This / this is / what we need : / a little bairam of concepts / a scouring of the intellect / in the eastern fashion / (a la maniere orientale) // aaa ! ! / to hell with everything !

References

- 1.Stern, Anatol. “Europa’’. Quoted from the Facsimile of the Gaberbocchus edition (First English Edition), London 1962.

Leave a Comment