Allegorical Landscapes

Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujică’s Videograms of a Revolution (1992), Radu Muntean’s The Paper Will Be Blue (2006) & Corneliu Porumboiu’s 12:08 East of Bucharest (2006)

Vol. 127 (September 2022) by Fabrizio Cilento

Written on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Romanian New Wave (Cristi Puiu’s 2001 Stuff and Dough is considered the starting point of the movement), this study explores allegorical landscapes in Videograms of a Revolution, The Paper Will Be Blue and 12:08 East of Bucharest. In these movies, heterogenous urban settings in Bucharest and Vaslui (which include the main squares and key symbolic buildings from different eras as well as peripheral spaces) are deployed as visualizations of the main characters’ struggles and as objective correlatives of their personal lives. As a consequence, if we bring the backgrounds to the front of our attention the emotional existence of the protagonists reverberates unexpectedly. Another peculiar aspect is that the interior spaces are not merely decorative, but gain figurative value thanks to the use of the frame within the frame and a cinematography that emphasizes the links between the inside and the outside (e.g. the picture of a square in a television studio, with the next shot moving to the real-life square, echoing the framing of the previously seen picture). Indoor and outdoor locations do not have an antithetical function, but complement each other. For this reason, it would be pointless to enforce a hierarchy between the two.

The Paper Will Be Blue and 12:08 East of Bucharest are among the rare New Wave works that address the Romanian Revolution and the controversies that accompanied the transition to the post-Communist era. What was the catalyst for the popular revolt? Who was responsible for the deaths of civilians? What was the nature of the changes that occurred in subsequent years? In reconstructing a recent event, the films do not incorporate amateur camerawork or newsreel footage (such materials are however displayed in the 1992 documentary Videograms of a Revolution by Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujică, whose collaborative film will serve as an object of comparison in my article). Yet the architectural spaces and the televised locations in which the revolution took place occupy a pivotal place in their narratives. While rejecting the reimagining of the revolution as an event in which the Romanian people showed their integrity by rising up collectively, these two films also discard both Communist nostalgia and (self-)exoticizing representations of Romania, which prevail in today’s age of globalization.

The originality of the Romanian auteurs does not lie in the topic they explore (which is undeniable), but in the techniques they employ to depict the landscapes through which everything else is expressed. The Art Nouveau villas, Soviet brutalist buildings, and post-industrial milieus at the edge of town spatialize the inner life of the characters. Although the days of the revolution were chaotic, by definition, what seduces the audience is the directors’ aspiration to establish visual order. The overall mise en scène, the minimalist movements within the frame, the capturing of a gesture, are all extremely controlled.

The Paper Will Be Blue and 12:08 East of Bucharest not only depict a historical reconstruction of the events, but also its psychological impact (which, as I discuss later, is particularly important in the case of the Romanian Revolution) that manifests itself in the distressful encounters between different characters and their interactions with their environment. During the revolution, there was a growing number of situations in which Romanian citizens felt disoriented, with some familiar spaces suddenly becoming unfamiliar, uninhabited, occupied by military forces and snipers, or facing destruction. The wounded city becomes an allegory for disillusionment, matching the topography of the minds of those who participated in the events either directly or indirectly. As landscapes come to symbolize something beyond themselves and their meaning does not lay in the immediately visible world,1 the revolution’s wasteland becomes a living entity. Conversely, outside of Bucharest, there are peripheral spaces that remain completely unchanged, which makes us question if an actual revolution ever took place to begin with, or if the revolution was an affair that only took place in the capital and other major cities like Timișoara.

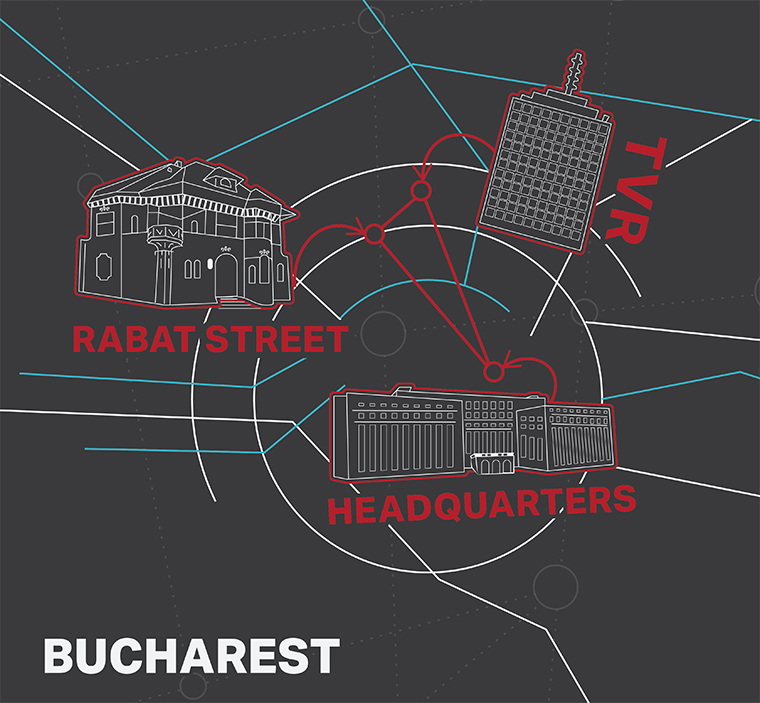

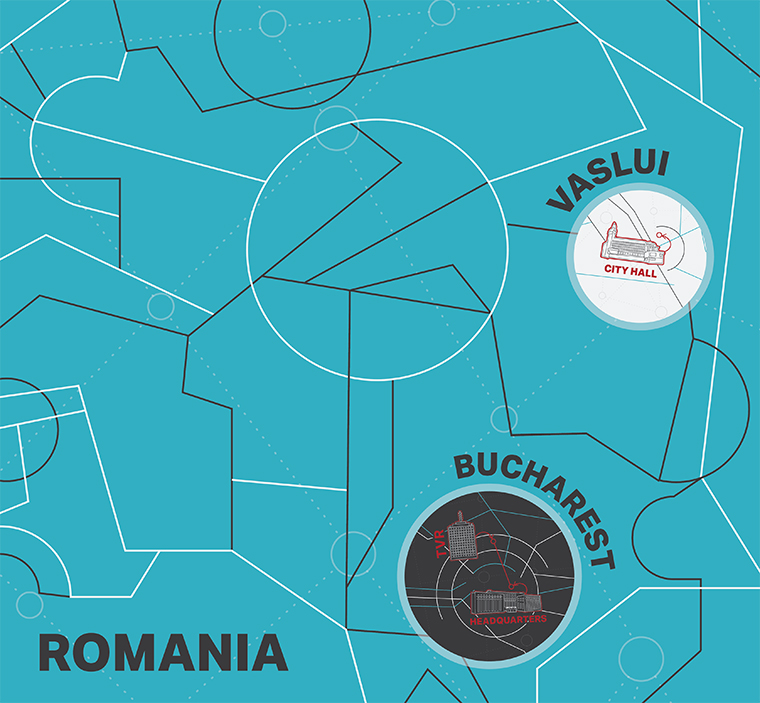

12:08 East of Bucharest engages with the reenactment of a local TV show (with its clumsy camera movements, poor photographic background, and random telephone calls), whose goal is to reconstruct whether or not there were revolutionary uprisings in Vaslui back in 1989. In The Paper Will Be Blue, set on the night of 22 December 1989, a member of the military’s Intervention Unit abandons his squad to defend the Televiziunea Românǎ Tower (TVR) in Bucharest. The tower was temporarily occupied by the National Salvation Front (FNS), which attempted to fend off Nicolae Ceaușescu’s alleged loyalists and help broadcast the revolution in real time. Because of a series of vicissitudes, the protagonist never arrives at his desired destination, but is arrested in an Art Nouveau villa in Rabat Street as the media outpost appears in a long central sequence. These sites are instrumental in reconstructing the short period of time – but a few hours – in which the soldiers learn about the revolution through television while themselves becoming agents of it. The motives of generalized forms of repression that resulted in over one thousand victims remain elusive. For this reason, directors Porumboiu and Muntean approach the events obliquely, creating hermeneutic circles between Cold War macrohistory, and the microhistories of ordinary people whose existence did not even occupy a short fragment in the massive coverage on national TV. The emphasis on the allegorical landscapes allows these movies to transcend the objective narration of the “facts” and reject the dichotomy between collaborationists and rebels, depicting a more ambiguous political system than the one fostered by the televised images of the revolution and impressed in the national subconscious. Filmmakers become contemporary cartographers, tracing alternative itineraries throughout Bucharest and Vaslui to illustrate the social turmoil and the urban alienation of the revolutionary and post-revolutionary days, while also interrogating the evanescent idea of national identity from 1989 up to our days.

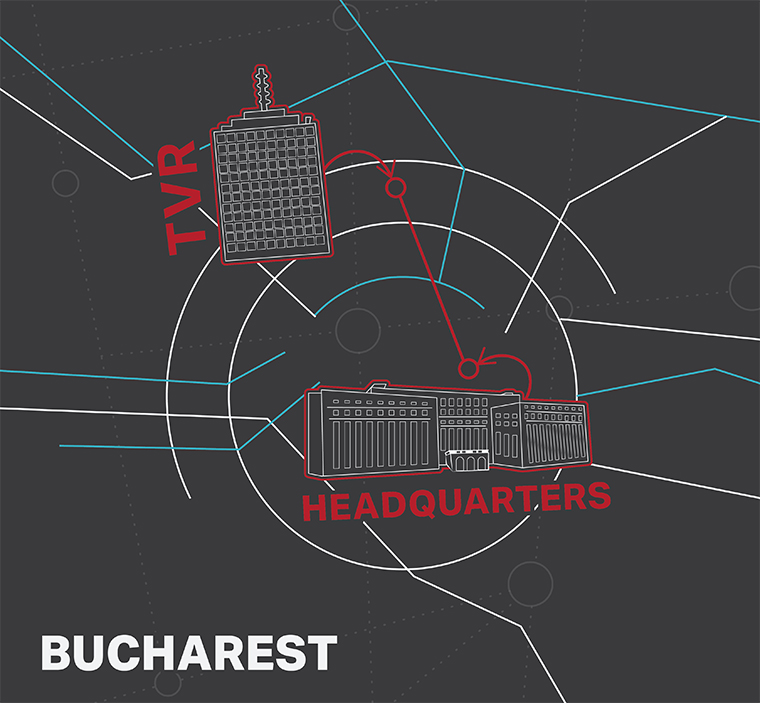

Bucharest: From the Communist Headquarters to the TVR Tower

Videograms of a Revolution establishes an axis in the urban space of Bucharest between the traditional lieu of power, the Central Committee Headquarters, from where the Communist Party operated from 1947 onwards, and the new media space of the Televiziunea Românǎ Tower.2 The first site is located on the Calea Victoriei side of Revolution Square (known as Palace Square until 1989), and dates back to the period immediately preceding the establishment of the Communist regime. Today the building is still associated with institutional power, as it hosts the Ministry of Interior and Administrative Reform. In front of it stands the former Royal Palace (the designated residence of the Kings of Romania from 1881 to 1947), which has been transformed into the National Museum of Art. In the square, multiple layers of Romanian history coexist in a remarkable balance. The second site – the TVR tower – is a Soviet modernist building designed by architect Tiberiu Ricci and his team in the mid-1960s, towering fifty meters high with 13 floors and a total surface area of 11,000 square meters. This and other brutalist constructions stand side by side with numerous fin de siècle villas, adding up to the Dorobanți neighborhood’s characteristic mix of residential and business spaces. During Communism, the TVR studios were an instrument of the government, charged with the dual task of promulgating information in the national interest and initiating their audiences into propaganda culture. National television aimed to present itself as a collection of unique, festive, and celebratory occasions: it had a tendency to propose a quasi-sacred presentation of every appearance of the dictator, valorizing each of his daily activities, travels and hobbies as an exceptional fact (this is evident in Ujică’s 2010 documentary The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceauşescu).

The visual history of the Romanian revolution begins on the lower balcony of the Communist Headquarters, from which Ceauşescu delivered his last public speech on 21 December 1989. The dictator had convened a mass rally in order to prove that he could still count on popular support after the violently repressed protests in Timișoara. Instead, the live broadcast only confirmed that his leadership was under threat, as viewers glimpsed for the first time the possibility that the regime could be overthrown. After an unidentified acoustic disturbance interrupted the speech, the masses suddenly began to shout aggressively.3 Caught by surprise at the unprecedented level of hatred directed towards him, Ceauşescu became stiff and started stammering until the television program was interrupted. In an attempt to hold onto power, the regime censored its own loss of control over the Romanian people.

Videograms deconstructs and reconstructs this famous moment, providing new elements of analysis. Farocki and Ujică split the screen into two quadrants to show what happened during the interruption. As shouts are heard, the camera shakes and the image glitches just before the director cuts to a blank red screen with the title “live broadcasting.” The bigger quadrant shows how the electromagnetic recording in the broadcasting van kept documenting the events that did not appear on TV. The cameraman had received instructions to pan to the sky if anything unexpected occurred, and he does so diligently. When the transmissions continue (without sound), only a few rooftops are visible in the frame under the blue sky of a clear, crisp winter day. (It is hard to overestimate how this shot, watched by almost the entirety of the nation, conditioned the future stylistic choices of Romanian New Wave directors. As I discuss later, both Muntean and Porumboiu avoid using upwards shots and keep the frame at ground level, over the shoulders of their characters, or, at other times, they film urban spaces in the opposite direction, from above to the ground.) After Ceauşescu took shelter inside, the swarms of people in Palace Square kept moving towards the main entrance of the Headquarters, overran the balcony, and started throwing books and papers off of it.

The spectacle of a tyrant unable to preach demagogic promises from his balcony galvanized the popular revolt in Bucharest. Having won the designated lieu of history, the crowds headed towards the novel one, the TVR Tower. Videograms incorporates the first announcement delivered from Studio 4 on December 22nd and the convulsive moments that preceded it. Stage and film actor Ion Caramitru introduces poet Mircea Dinescu, who, in a sweaty and battered sweater, proclaims victory and appeals to the Army to join the revolution and demands amnesty for those who are being prosecuted. Behind his desk, there are about forty members of the newly constituted FNS, a group composed by a heterogenous coalition of dissidents that included politicians, artists, students, architects, and various Army officers. From this moment on, TVR became the epicenter of the revolution, both as a physical space and as a media space: an instrument for citizens, international commentators, and the military itself to monitor in real time how the revolution was unfolding. This mission culminated in reporting the trial and subsequent execution of the dictator and his wife Elena that took place on December 25 and was edited by film director Sergiu Nicolaescu. In the words of many announcements in the press, “the Antichrist died on Christmas Day”.4

Up at the Villa (Rabat Street, Bucharest)

The Paper Will Be Blue adds a new element of interest to the itinerary that takes us from the Central Committee Headquarters to the TVR Tower traced by Videograms (that is, from the edifice that houses the old power of the regime to the one that houses the new televisual power) by taking a detour to an Art Nouveau villa in Rabat Street, where members of the elite used to reside during the Communist regime. During the 1989 turmoil, the villa was temporarily occupied by the revolutionary Army. Rather than setting its narrative on the axis that connects two symbolic buildings, Muntean’s film displays a spatial triangulation.

The film is set on the night between December 22nd and December 23rd. It portrays Costi Andronescu (Paul Ipate), a young deserter who was deployed by an Internal Affairs Unit. After hearing on Radio Free Europe that the TVR Tower is being attacked by pro-Communist forces, Costi abandons his squad to join the ranks of the FNS and go defend the building. However, due to a series of mishaps, he never arrives at the desired destination and only makes it as far as Rabat Street. As he enters the 19th century home, Costi is astonished to find fine perfumes in the bathroom on the first floor, and embarks on a sensory exploration, sniffing the fancy-colored glass bottles. He is also enchanted by the wooden antique furniture, Persian rugs, decadent paintings, chandeliers, and the wine and champagne collection in the cellar. However, there is no time for him to further contemplate the luxurious interiors. Captain Crăciun (Ioan Săpdaru) instructs him to defend the building from the upper floor. As a trained sharpshooter, Costi hits one of his targets, only to find out that he is responding to friendly fire. Costi informs Crăciun of the accident, but instead of being praised for his honesty, he is arrested under the suspicion of being a terrorist. This reflects the confusion that pervaded that night. What caused the friendly fire? Were there really Ceauşescu loyalists (or even terrorists) among the revolutionaries, and if so, who were they? Was this an invention of the regime, so that the anti-Ceauşescu faction within the government would continue to rule? What is the line that separates a victim from a perpetrator, or a revolutionary from a terrorist? The film resists narrative closure and settles on the unstable ground where illusion meets actual events, lies meet other lies, and nothing is what it seems.

Meanwhile, members of Costi’s Unit arrive at the TVR Tower, where they hope to find their missing peer. In a pivotal sequence, Muntean leads us through the labyrinthine interior structure of the media outpost, which is serving as a military operations center. In order to find out what is happening, the military looks at black-and-white images on the mini-television screens in their newly commandeered offices.5 The Paper Will Be Blue shows how the military acted both as an agent of the revolution and as a TV host, occasionally addressing the population, and thus producing the “reality” of the revolution in real time.6 These circumstances have not escaped Baudrillard, who dedicates a chapter of The Illusion of the End (1994) to the Romanian Revolution. The theorist underlines how, in December 1989, propaganda was taken to a new level: it was not just a case of misrepresenting what was happening in Romania, but a case of fabricating what was going to happen in advance so that it would actually happen.7 The Romanian Revolution was TV-induced. It was fought through speculations and simulations of what might happen (not through depictions of what was actually happening) to make sure that the collapse of the Ceauşescu regime would occur.

Another summary of these events comes from philosopher Agamben, who writes in Means with No End: “The secret police conspired against itself to overthrow the old spectacle-concentrated regime while television showed the political function of the media. Truth and falsity became indistinguishable from each other, and the spectacle legitimized itself solely through the spectacle”.8 The titles of both Baudrillard and Agamben’s books emphasize the lack of resolution after the Romanian Revolution. Both thinkers approach the event as a missed revolution, as half a revolution, or, in the most generous of hypotheses, a quasi-revolution. The FNS appearances on screen, which called on the population to defend various public places, were perceived by the people as chronicles of the revolution and not as media artifacts, the authorities on screen themselves retelling what they had seen or what was reported to them. Functioning as an ideological machinery designed to render the events intelligible, TVR was “instrumental in mediating revolutionary misrecognition”.9 The ontological connection between image and reality was inverted: rather than documenting actions, images generated other actions. Events did not exist to be recorded and presented as images for an audience, but served as a self-fulfilling prophecy. “The television broadcast showed that the image is not based on a specific articulation of history; on the contrary, an understanding of history is articulated on the basis of the image”.10 Hence, the importance of showing what was not televised, such as the sacrifice of Costi and his squad in The Paper Will Be Blue. These observations are pertinent to 12:08 East of Bucharest as well. As I will argue in the next section, Porumboiu’s film illuminates the impact of the narrative model provided by TVR on regional channels, as well as the persistence of this model in the new millennium. In Romanian films about the revolution, television is both visible as an architectural space (the actual studios) and as a mental or psychological space.

After the unsuccessful search for Costi in the TVR studios, his former Unit consults the urban map in order to understand how to arrive at the Arch of Triumph in the central part of the city without getting caught up in the riots. Half the size of its illustrious Parisian counterpart, this monument was designed by Petre Antonescu with the contribution of prominent Romanian sculptors. The third in a row built between 1878 (when Romania became an independent state) and 1936, the arch has traditionally been the main focus of National Day celebrations. Yet, the director keeps the camera at ground level, resisting the temptation to point the camera towards the sky and show the monument as the soldiers get out of the tank in front of it, smoking and talking to each other at length about what passwords they need to use and what the situation at the TVR Tower is. Muntean aims to subvert the consumerist and de-historicizing gaze that often invests depictions of monumental Bucharest, labeling it as “little Paris” or “the Paris of the East.” But above all, as in the previously discussed footage of Videograms, when it comes to images and reconstructions of the revolution, pointing the camera toward the sky is a movement that in the collective visual subconscious is associated with Ceauşescu’s regime. Muntean belongs to the generation of those who were born in the 1970s, of those who are earthbound.

Inglorious Landscapes: From Bucharest to Vaslui

Another visual trend that New Wave directors avoid is that of Communist nostalgia. To this end, the Romanian poster of 12:08 East of Bucharest, with the City Hall of Vaslui in the background, is more accurate when it comes to conveying the film’s main tenets. The open-ended question of the original title, in which the word “revolution” is not even mentioned, along with the emptiness of the square, has a metaphysical undertone to it. The difference between these visuals and the images of protesters storming the Communist Headquarters in Bucharest, is striking. The English poster instead presents a closer shot of Vaslui’s City Hall with a red background and a superimposed hammer and sickle placed on the ground at the bottom of the statue of national hero Stephen the Great (1457–1504). This design misleadingly associates the film with the Ostalgie trend that produced films such as Wolfgang Becker’s Good Bye, Lenin! (2003) and Carsten Fiebeler’s Kleinruppin Forever (2004), which gained momentum internationally in the early 2000s. On the bright side, the English title emphasizes the importance of the spatial-temporal dimension that permeates the narrative of the film. 12:08 PM is the time at which Ceauşescu fled by helicopter from the roof of the Communist Headquarters on 22 December 1989, but the date is not mentioned in order to reproduce the elusiveness of the Romanian title.11 Even the location is recognizable but never mentioned in the screenplay in order to preserve the universal appeal of the story and to emphasize the uneven relationship between the city of Vaslui and the capital of Romania. The Moldavian town has about 70,000 inhabitants, and evolved into an important administrative center during Communism, when a sprawling bureaucracy quickly took over everyday life. The Soviet architectural style that characterizes the city reflects its recent history, and contrasts with the woods, the green hills, and hunting areas that surround it.

12:08 poses questions about the revolution similar to the ones asked by The Paper Will Be Blue, but retroactively, since it is set in the present tense, approaching the revolution from a minoritarian perspective. The film opens with five tableaux, effectively rendered by Marius Panduru’s camerawork,12 which show the lights of the town of Vaslui as they are switched off at twilight. There are no people in the frame, only concrete buildings during a long Romanian winter. The first shot is of Vaslui’s City Hall. An imposing Christmas tree and the vast number of lights suggest that we are in the post-Ceauşescu era, for the regime would never have tolerated such displays, which were considered a waste of resources. In the last years of Communism, electricity was rationed, and cities were plagued by frequent black outs.13 Porumbiou cuts to five additional views of the awakening city: a large boulevard seen from a rooftop; a shot of a street with a wall obstructing the right half of the screen; a plateau seen from one of the Tutova Hills; the lower section of a brutalist building; and an anonymous five-story condo.

After the prelude, the first half of the movie focuses on the everyday lives of the three main characters, which are intercut via parallel montage. In the run-down living rooms of the apartments in which the town’s inhabitants live, televisions are losing their signals. The 16th anniversary of the revolution gives Virgil Jderescu (Teodor Corban), a local television host, a pretext for recalling the happenings of 22 December 1989. As some of the panelists turn out to be unavailable (a symptom of the shared reluctance to analyze the revolutionary days), Jderescu runs out of alternatives, and ends up inviting two hapless guests: Emanoil Piscoci (Mercea Andreescu), a retired Santa Claus impersonator, and Tiberiu Mănescu (Ion Sapdaru), a debt-ridden, alcoholic high-school history teacher full of debts. The various narrative segments converge when Jderescu gives his hosts a car ride to the TV studios. The uneventful journey occupies a long camera car sequence that serves to reveal Vaslui’s post-industrial environment in all its decadence. In commenting on the urban landscape as it emerges in Central and Eastern European cinema, Dina Iordanova refers to “visions of metaphoric grayness”.14 These epitomize the political stagnation that characterized the geographical area and, in countries such as Romania, shows a certain continuity between the Communist and the post-Communist eras. Through a powerful articulation, however, rather than reinforcing the negative stereotypes that surround Romanian locations, the filmmaker conceives this extended shot to unapologetically celebrate the pure cinematic power and the perverse beauty of such sites. As gloomy, colorless, and monotonous as they are, these inglorious landscapes become an objective correlative of the existential void that haunts the main characters. As we have already seen, The Paper Will Be Blue and 12:08 East of Bucharest display multiple historical architectural layers – fin de siècle villas and brutalist constructions, prefabricated blocks with dark windows, crumbling walls and chimneys and abandoned factories. Grimy Dacias, Škodas, and Mercedes-Benzes with unlikely colors and questionable brakes drive through streets overhung with agonizingly contorted trees. The asphalt threatens to turn into mud puddles at every turn, while flickering lamps and TV reflections sparkle in the windows of the outlying areas of anonymous-looking towns.

If one were to analyze the phenomenological approach of Romanian New Wave directors using classic concepts in film studies, one could say that The Paper Will Be Blue and 12:08 East of Bucharest present a cinematic style whose techniques include a preference for location shooting, a documentary style of photography, natural lighting, a mix of professional and nonprofessional actors, and a non-interventionist approach to film directing. At first sight, the flow of life in Romanian cinema is similar to that celebrated in Western European high modernist cinema by international film theorists such as André Bazin and Siegfried Kracauer (and effectively emphasized by long, uncut sequences). This style is most evident in the streets in which the materiality of built space corresponds with social interaction and is particularly intense in moments of abrupt modernization or historical and political crisis: from the representation of Italian ruinous and bombed-out neorealist cityscapes in the immediate postwar era (1945-1948) to the French New Wave (1959-1963), in which Paris traditionally ‘belongs’ to the auteurs. Yet, the innovative charge of Romanian movies lays in blending the high modernist canon with the immediacy of televisual liveness. The presence of television in Romanian movies (I am referring not only to the studios themselves, but also to the presence of media devices in the various apartments) creates a new level of interplay between newsreel aesthetics and a profound historical reflection about the 1989 events initiated by the filmmakers from the vantage point of the new millennium.

Although urban space remains crucial to the narrative, in the second half of 12:08 the characters are reduced to televisual talking heads. A comparison between the pitiful conditions of the media facilities in Vaslui, and Bucharest’s Studio 4 as it appears in Videograms (so spacious and full of authoritative figures), makes us wonder once again what role the small town may have possibly played in exacting the end of the Communist regime. In Porumboiu’s film, everything appears as a toned-down and ‘depressed’ version of the memorable TVR footage.

At the beginning of the commemorative program within the film, the host invites his guests to reveal what they did around noon on 22 December 1989. If the people of Vaslui converged into the street before 12:08 PM, this means that there were revolutionary activities in town. If they converged into the streets after that, Vaslui’s citizens had no active role in the downturn of the regime: they were just celebrating the events that took place in Bucharest. In his opening monologue Jderescu quotes Plato’s myth of the cave:

Many of you may wonder why we still have a talk show about such a topic after such a long time. Eh, to be honest, I think that… in accordance to… well, as in Plato’s Myth of the Cave, when people mistook a small fire for the sun, well… I think that it is my duty as a journalist to ask whether we left the cave so that we may enter an even bigger cave… and if we, in turn, are not mistaking a straw fire for the sun.

These words associate the Greek myth of the cave of shadows with the self-enclosed media space that the characters inhabit. Such interior locations are as important as the exterior spaces in which the battles took place and the crowds protested against Ceauşescu. Batori remarks how claustrophobic the spaces of television are in Porumboiu’s film, and emphasizes how Jderescu, Manescu, and Piscoci are smashed against the background, as if they were imprisoned and under the kind of surveillance typical of the regime. Their images are captured from a fixed, central standpoint, thus creating portrait-like, symmetrical compositions. The characters are incapable of escaping the frontal gaze of the camera, which scrutinizes their statements, reactions, and expressions.15 The studio background is a picture of the City Hall in its 1989 state. Yet, a carefully composed mise en abyme emerges, since this picture does not always occupy the whole background frame. This is shown to be due to the clumsiness of the operator Costel (Lucian Iftime), who is shooting with a broken tripod. Furthermore, because the square is empty in the photograph, it closely resembles the tableau that opens the film, accentuating the osmotic relationship between the interior and exterior spaces.

During their conversation, Manescu describes Vaslui as a “frozen city,” confirming that the urban space has not been revitalized during the years that separate the revolution from the TV program. The professor claims that he and three other colleagues started singing slogans against Communism, threw stones at the City Council windows, and then tried to break into the building, before the Securitate (the secret police) turned up to stop them. However, people followed their lead as they foresaw the long-awaited end of the regime, emerging from the factories, from the main avenue, and from the park. At this point, Manescu establishes a quasi-tactile relation with the image on the background when he points at a corner to mark the spot from where the crowds emerged. The rapport between the characters and the black-and-white picture of Vaslui is reestablished soon after, when a former guard for the City Council named Vasile Rebegea intervenes in the program via a live telephone call. He states where he would have been in the shot: a sentry box that all recall being up at the time, where he was doing his shift on December 22nd. The sentry is located in the right corner of the background photo, behind the head of Piscoci, who moves to allow viewers to see the spot in question. As with many other callers, Rebegea asserts that it was only after Ceauşescu fled by helicopter that people started appearing in the square. Interestingly, even Vasile, no different from the soldiers in The Paper Will Be Blue, learned about the revolutionary events by watching TV on his shift. At this point, Piscoci challenges everybody else’s version of events, claiming that the guard in the sentry box could not have seen the teacher protesting because the latter was in front of the statue of Stephen the Great, and thus outside of his field of vision. This reconstruction generates a comical effect.

After an almost muted start, in which he seemed to be absent-mindedly building paper boats, Piscoci takes over the scene and monopolizes the last few minutes of the broadcast. He recounts how, on that special day, he was trying to win back the affection of his (now deceased) wife Maria by offering her “three splendid magnolias” plucked from the botanical garden. Suddenly, the Tom and Jerry and Laurel and Hardy episodes on TV were interrupted by a besieged Ceauşescu promising a wage increase of 100 lei. Piscoci was hoping to use the money on a trip to the seaside in Mangalia with his wife, to visit the Tropaeum Traiani in Adamclisi on the coast of the Black Sea. In expanding the geography of the film, the old man confirms how most people in Vaslui tend to imagine themselves somewhere else, may it be in Paris, Bucharest, or Mangalia. With disarming candor, he confesses that the advent of revolution frustrated him, because it came in the way of his vacation plans.

More importantly, Piscoci re-opens the ‘lightmotif’ of the movie. He says that the revolution started in Timişoara and then in Bucharest before spreading throughout the whole country, including to the “middle of nowhere,” which is Vaslui. In doing so, he compares the revolution to streetlights: they are lit starting from the center and then move on to the marginal streets. In a similar way, the revolution spread from Bucharest to the rest of the country. At this point Manescu contradicts him: “We all know that the Christmas streetlights turn on at the same time. What’s the revolution got to do with the streetlights?” Piscoci responds that people in Vaslui are cowards and joined the revolution after Ceauşescu had fled. This discussion reinforces the contrast between natural and electric light that frames the film, but may also be a commentary on the failed attempt of Manescu, Jderescu and Piscoci to embrace Enlightment philosophy (pun intended). They engage in a fantasy of liberation associated with Western democracies. (Manescu assigns a quiz to his students on the French Revolution in the first half of the movie, while Jderescu compares the storming of the Central Committee Headquarters in Bucharest to the storming of the Bastille.) The film also refers to the tropes of investigative journalism and to the achievement of high technological standards. It is not by chance that the turn toward a bastardized version of a Western democracy in Romania happens through impersonal “non-places”16 such as the national and regional television studios. These are the impersonal sites typical of the waves of globalization which made the world converge after 1989 and have led us toward universally uniform architecture. In Romania, the anti-Ceauşescu faction within the Communist Party engaged in a constructed media conspiracy: it performed Western ideals in front of the cameras while maintaining strong links with the country’s controversial political past behind the scenes, making audiences believe that the country was turning the page politically. For this reason, it is hard to decipher the historical events or approach them objectively, even in retrospect. In this sense, 12:08 East of Bucharest is not a movie about the revolution, but a self-reflexive film about how difficult it is to reconstruct the events that surrounded it.

In the epilogue, which coincides with the end of the day, public lights are flickering on as the evening is approaching, while the voice-over of cameraman Costel states that the revolution was similar to the cityscape of Vaslui: “peaceful and nice.” This comment, and the symbolic end of darkness, allude to the beginning of a new epoch in the history of Romania, but also to the fact that there was no turmoil in Vaslui, and that there is not much difference between what one would expect from life under socialism and the present. In their previous exchanges, Manescu and Piscoci could not even agree about how the city light system works. The cameraman returns to the debate and agrees with the professor, claiming that all the lights come out at the same time, thanks to the invention of the photoelectric cell. Porumboiu concludes his debut feature by contradicting all of his characters. He shows that the city lights move from the margins to the main square. In fact, as luminescence returns, the five initial tableaux are shown in reverse order – the film becomes an ode to the importance of the periphery and the sparks of vitality of those who inhabit it. In tune with the message of the film, this underscores the fact that there were spasms of life and creativity at the margins of the former Communist empire. In this sense, “the tableau appears not only as a liminal space conceived between the visible and the invisible, the grand theatre of politics and the private world of everyday people, it also reveals in different ways the shifting demarcation between the ‘public’ and the ‘domestic’”.17 Sixteen years after the events, Vaslui is a place where no one agrees on anything, but where a polyphony of contradictory opinions on the revolution becomes a minor spectacle within the main spectacle staged in 1989 at TVR by dissident actors, poets, and men in uniform. But it is snowing, and it is almost Christmas, and as the evening approaches, even some of the ugliest buildings of the small town flaunt a sort of sinister beauty.

Conclusion

This study has illustrated how the film locations of Videograms of a Revolution, The Paper Will Be Blue, and 12:08 East of Bucharest are objective correlatives of the struggles of the protagonists Costi, Jderescu, Manescu, and Piscoci, whose lives were impacted by the 1989 revolution at different levels. The allegorical landscapes shed an unexpected light on the sociopolitical turmoil and its perceptual effects on ordinary people, while countering both Communist nostalgia and exoticizing portrayals of the country. The spaces depicted in the films are heterogenous and belong to various eras, ranging from the iconic Central Committee Headquarters and the Televiziunea Românǎ Tower to an Art Nouveau villa in Rabat Street, Bucharest. In a moment in which the connotations of these buildings were rapidly changing, the interactions between human beings and architecture serve to defamiliarize these iconic constructions. A synoptic approach to these films also reveals how Bucharest had an uneven relationship with peripheral towns such as Vaslui, whose Soviet brutalist architecture and low-key television studios emphasize the continuity between the Communist and post-Communist period.

A dialectic between interior and exterior spaces pervades the films analyzed above. The interiors are disorienting and full of reflective surfaces. They are often the designated media outposts in which a fictional narration of the revolution unfolds, either in real time or in retrospect. Thanks to a minimalist approach and the expedient of the frame within the frame, the directors construct a complex discourse on the relationship between what actually happened (the quasi-revolution, or the missed revolution) and the reconstituted reportages which perpetrated the archetypal epic of the French Revolution. The protagonists initially try to conform to the heroic rhetoric imposed by professional or improvised TV hosts, but this only leads to embarrassment, shame, and at times even culminates in the loss of their own lives. In this sense, the gloomy, colorless, and monotonous landscapes on screen reproduce the lack of existential purpose and the ideological void that haunted most of the country at a pivotal historical turning point.

References

- 1.Melbye, D. (2010). Landscape Allegory in Cinema: From Wilderness to Wasteland. Palgrave Macmillan, 3.

- 2.Young, B. (2004). On Media and Democratic Politics: Videograms of a Revolution. In T. Elsaesser, (Ed.), Harun Farocki: Working on the Sight-Lines (pp. 245-260). Amsterdam University Press, 247.

- 3.For a humorous fictionalization of this moment, see Cătălin Mitulescu’s The Way I Spent The End of the World. In the final sequence, seven-year-old Laliu, who visits the Palace Square with his children’s choir, uses a sling to fire a stone against the leader. This act causes the leader to stumble and sparks a mass protest. Mitulescu mixes original archival footage with the one created for the film, in which the child appears to raise his thumb to signal to his family (whose members are watching the broadcast from home) that everything is fine before he takes action. The fictionalized reconstruction thereby appears to be an integral part of the TVR transmissions. Since even in the film, the slingshot event is merely imagined by one of the protagonists, it may be intended as a commentary on the constructed nature of broadcasting itself.

- 4.Codrescu, A. (1991). The Hole in the Flag. William Morrow and Company, 25.

- 5.This moment is similar to the hyperreal episode narrated by Patton in the introduction to the US edition of Baudrillard’s The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, when the news channel CNN switches to a group of reporters live in the Gulf to ask them what is happening, only to discover that they are watching CNN to find out themselves. Baudrillard, J. (1995). The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. Indiana University Press, 2.

- 6.General Ștefan Gușă was the first man in uniform to appear on TV. He announced that the Army was with the people. Along with him, General Iulian Vlad (the head of Securitate, the secret police) claimed to have joined the revolution as well.

- 7.As Baudrillard writes, “one might almost feel sorry that entire peoples are coming out of their darkness, even if it was violent and tyrannical, to fall prey to the Enlightenment, to go down like flies in the artificial light of our freedom, our unbounded solidarity, our unscrupulous news system. We who so respect the private life of individuals should also respect that of peoples and their rights – against all international morality – to escape this modern tribunal of news and information-gathering which is assuming all the features of an inquisition. For only information has sovereign rights, since it controls the right to existence’’ (Baudrillard, J. (1994). The Illusion of the End. Stanford University Press, 59).

- 8.Agamben, G. (2000). Means with no end. University of Minnesota Press, 11.

- 9.Parvulescu, C. (2013). Depicting the 1989 Events in the Romanian Historical Film of the Twenty-First Century. In R. Rosenstone, & C. Parvulescu (eds.), A Companion to the Historical Film (pp. 365-383). Wiley-Blackwell, p. 371.

- 10.Strausz, L. (2017). Hesitant Histories on the Romanian Screen. Palgrave MacMillan, 4.

- 11.Bardan, A. (2012). Corneliu Porumboiu’s 12: 08 East of Bucharest (2006) and Romanian Cinema. In A. Imre (ed.), A companion to Eastern European cinema (pp. 125-147). John Wiley & Sons, 125.

- 12.Nasta, D. (2013). Contemporary Romanian Cinema: The History of an Unexpected Miracle. Columbia University Press, 170.

- 13.For a timely revisitation of that period, see Mungiu’s omnibus film Tales from the Golden Age (2009), which ironically stresses that there was nothing splendid about the regime.

- 14.Iordanova, D. (2003). Cinema of the Other Europe: The Industry and Artistry of East Central European Film. Wallflower Press, 93.

- 15.Batori, A. (2018). Space in Romanian and Hungarian Cinema. Palgrave MacMillan, 122.

- 16.Augé, M. (2008). Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. Verso, VII- XV.

- 17.Pethő, Á. (2019). `Exhibited Space’ and Intermediality in the Films of Corneliu Porumboiu. In C. Stojanova, & D. Duma (Eds.), The New Romanian Cinema (pp. 65-79). Edinburgh University Press, 67.

Leave a Comment