The past can only be transmitted in the form of ruins, monuments, bric-a-brac in retro. The stroke of lightning is like hypnosis.

– Marina Gržinić and Aina Šmid, Bilocation, 1990.1

“He loved and yet he killed me.” A woman smiles ecstatically. Thick red blood streams from a cut above the bust. Her Madonna-like body “is simultaneously heroically exposed and stigmatized.”2 In a fish tank a Buddha statue’s severed head is laid to rest – until the water turns into blood. Red walls, red flowers, red lips. The experimental video Axis of Life (Os življenja, 1987) tells the violent story of two women that is performed by the directors Marina Gržinić and Aina Šmid themselves.

Marina Gržinić and Aina Šmid have been collaborating on video and media installations since 1982. Their work reflects both women’s experience of living and working under ever-shifting social, technological, and economic conditions. Video is a playful medium that expands on the artists’ theoretical work in philosophy (Gržinić) and art history (Šmid). While their early videos paint an absurdist portrait of late socialist Yugoslav society, their recent work explores contemporary turbo-capitalism.

Both women in Axis of Life reminisce about how they killed their husband. (We don’t know exactly whether they are referring to the same man.) By turns vampire noir and Communist detective flick, Axis of Life is a six-minute montage of twists and turns driven by bloodlust. Gržinić and Šmid’s disembodied voices tell their versions of the past. We keep wondering who is dead and who is alive.

Video is a territory “impregnated with blood,” writes Gržinić in a later text. Video’s ability to join “the edges where two or more video images, or pages, collide – is not merely the intersection of juxtaposed empty scenes; on the contrary, this suture can be the bloodstain of excess.”3 With Georges Bataille, Gržinić’s bloodstain of excess describes an overflow of intensity. Images here are not empty placeholders in a montage. They are violent collisions. If Sergei Eisenstein used collision to create shocks, in Gržinić and Šmid’s work video itself is shock. The image is oversaturated.

“But, you remember. It had to happen… I had to die.” Did they kill their husband, or did he murder them? “We could not kill him, so we charged him with murder.” Memories and dreams create a hyperreality. Axis of Life demands to be watched repeatedly, in an eternal loop. It is less a self-contained clip than fragmented memories of other half-remembered films.

Blending electronic sound and synthesized video, Gržinić and Šmid recycle snippets from their black-and-white At Home (Doma, 1986), the story of a man who is forced to murder his wife during the Second World War. After the war, he falls in love with another woman whom he eventually also kills.

The different stories in At Home intersect and contradict each other: memory is too unreliable to recall what happened (“No, I don’t remember this”). There is no original narrative to reconstruct. Violence is the red threat running through both videos. At Home, according to the artists, is a homage to Hitchcock — an impossible one “because it is an attempt to make Hitchcockian suspense out of the socrealistic imagery and content.”4

The eerie subtext of the video draws on the Stalinist purges, the Second World War and the Cold War, visualized though it is in images drawing on American Pop art. In the three-minute video Cindy Sherman or Hysteria Production Presents a Reconstruction of Sherman’s Photographs (Cindy Sherman ali histerija produkcija predstavlja rekonstrukcijo fotografij Cindy Sherman, 1984), the artists began to ironically appropriate imagery from iconic American artists. Fragments from Sherman’s photos are restaged and recycled, transforming an already self-referential body of work.

With plenty of anarchic humor, late Yugoslav video art parodies socialist realism, the official doctrine in post-war Eastern Europe. “Socrealism” demanded a bright portrait of society heading towards an even brighter future. Gržinić and Šmid’s surrealistic montages uniquely subvert the prefabricated imagery of official socialist art. Instead, they enjoy the bloodstains of transgression and excess. In Gržinić and Šmid’s universe, bloodthirst is jouissance.

From Hitchcock, Gržinić and Šmid appropriate a love for uncanny voyeurism and horror. Copying Hitchcock’s Frenzy (1972), the staircase shot in Axis of Life destroys the linearity of events created in At Home (1986). Haunted by ghostly memories (or forecasts?) of war, At Home paves the way for Gržinić and Šmid’s critical intervention into Slovenian society that lasts until today.

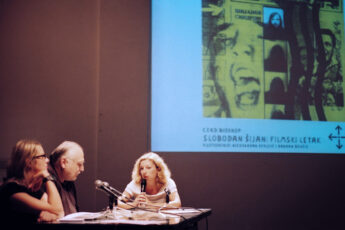

This year’s retrospective at Galerija Loža in Koper, Slovenia, marked the 40th anniversary of their collaboration.5 More recently, Gržinić and Šmid have been investigating capitalism, technology and biopolitics. Their unique vision, however, already crystallizes in their early videos. It is here that the viscerality of the medium, video as a territory “impregnated with blood,” becomes most palpable.

In the 1980s, Gržinić and Šmid “attempted to find out if we could apply our feminist and radical ideas about art and politics to a critical interrogation of socialism and its ideology.”6 Their early experiments with video were critical of ideology in all its shapes and forms: from American mass culture to Yugoslavia’s state apparatus.

As a “medium of subculture”7, Gržinić writes, video “is very easy to use and manipulate, hence it is important to develop primarily its political-conceptual prerogatives, dismantling aesthetic, languages and discourses.”8 Video itself is a technology of repetition, copying and manipulation – the perfect medium to produce politically engaged art with little means and beyond official institutions.

The dismantling of late socialist society was at the heart of Gržinić and Šmid’s early work. Yugoslavia’s final decade, preceding the bloody wars of the 1990s, opened with a double event: the death of Josip Broz Tito and the emergence of the punk movement. After Tito’s death, “the main structural pillars of Yugoslav society – non-alignment, self-management, the revolutionary legacy and brotherhood and unity, began to show the first signs of erosion.“9

In the midst of social and economic crisis, the Slovenian underground was born: playful, radical, queer. Ljubljana became a creative haven for artists, musicians, filmmakers and theorists. In Slovenia’s capital, art collectives such as Laibach, the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre and IRWIN – later joining forces as the Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK) – created eclectic work that still polarizes today. Gržinić and Šmid’s practice is firmly rooted in this subcultural underground. In their early videos, feminism and gay culture were “coming out into socialism.”10

Icons of Glamour, Echoes of Death (Ikone glamurja, odmevi smrti, 1982) creates the phantasmagoric world of a model (Gržinić) who transitions between sexes and her friend, a hermaphrodite (Šmid). Since the 1970s, Gržinić writes, “it became clear for many of us that sex and gender are not some natural states, but are always formed in connection with a particular social relation.”11

Contrary to any binary opposition, in Gržinić and Šmid’s videos gender boundaries become fluid. In Bare Spring (Gola pomlad, 1987), the male protagonist confesses his cross-dressing habits: “I’ve learned everything by watching. Without those pictures we wouldn’t exist either.” The pictures he refers to emerge from the new visual language developed in Slovenia’s underground. Using strategies of recycling, Gržinić and Šmid also interweave images of women from their earlier video work with images of works by Cindy Sherman.

Icons of Glamour, Echoes of Death’s dreamy conversations evoke Kathy Acker’s pornographic prose. The model remembers her first encounter with sexuality: “Once, when I was in the seventh grade and had just come from the cellar, I met my neighbor. [He] came and asked me, if I ever wanked it off. And I didn’t know at all what it was all about. I was very embarrassed and he wanked me off.” After a pause, now directly gazing into the camera: “Since then I wank all the time.”

The radical Icons of Glamour is arguably the first artwork in socialist Slovenia to openly celebrate homosexuality, drag, transgender and sadomasochism. Produced by ŠKUC-Forum in Ljubljana, the video is an important forerunner of feminism and LGBTQ+ culture in Slovenia. In April 1984, the ŠKUC-Forum organized the festival Magnus: Homosexuality and Culture, which showed European and American gay films, exhibitions, and lectures on gay culture.

“These two movements (punk and homosexuality),” Gržinić recalls, “transformed us into urban entities; they opened up the possibility of conceptualizing anti-authoritativeness, different sexualities, the anti-hegemonic battle against patriarchy and chauvinism, the normalization of everyday life, and the revolt against depoliticisation.”12 The Magnus festival, very much in the spirit of Icons of Glamour, marked the beginning of a vibrant lesbian and gay scene in Slovenia: “before being feminists, we were lesbians,”13 Gržinić writes.

Doubling and doubt, crucial to Icons of Glamour, also shape their video works on war. In Axis of Life, for example, the women’s individual identities blur; though both continuously refer to their murdered husband, the relation between the two women takes center stage.

Similar strategies of doubling can be seen in the first part of Gržinić and Šmid’s rather unusual war trilogy, Moments of Decision (Trenutki odločitve, 1985). Heavily collaging, superimposing, restaging and recycling images, the video is a “remake” of Czech director Frantisek Čap’s 1950s partisan film of the same title. Through video-effects one of the actresses is superimposed over Čap’s lead actress, evoking the (im)possible simultaneity of characters and events.

“All of a sudden,” the voice-over muses, “I see myself as some other girl, like some other girl could be seen from the outside, placed amidst the traffic of cities, roads, desires.” Cutting through the two-dimensionality of the movie screen, Moments of Decision creates a theatrical space of multiple identities. Double acting and blue-key effects rewrite Čap’s story, transforming it into a melodrama that draws on autobiographical memories, Marguerite Duras’ novel The Lover and fragments from the original screenplay that had been censored in the 1950s. An uncanny temporality haunts the video: “Very early in my life it was too late.”

Similarly, the female protagonist in Girl With An Orange (Deklica z oranžo, 1987) walks through her family home, confronted by memories of her youth, while a man with a camera follows her. Sleepwalking, the woman sees herself in the mirror, framed by paintings by Kazimir Malevich and René Magritte. In this dream world, the past is out of joint. Broken glasses are fixed, forgotten childhood names evoked.

Again, two women are present: one reminiscing, the other acting. The man with the camera interviews the protagonist, while they pass taxidermied birds. “Life is all there is,” she says. “Yes, but what kind of life is it?,” he asks. Are the memories he shows her on TV her own? Like in Moments of Decision, the woman sees herself from the outside, as some other woman, incapable of going back in time.

Being too-late is a returning motif in Gržinić and Šmid’s early work. While Thirst (Žed, 1989) tells the story of a man facing his lost time and indispensable future, The Threat of the Future (Grožnja prihodnosti, 1983) traps the viewer in an apocalyptic punk peep show. In her theoretical writings, Gržinić calls this state “retro-avantgarde:”14 a cultural zero-point at which artists rediscover and ironically reappropriate the utopian spirit of the prewar avantgarde. Gržinić considers “the re-appropriation of history“15 crucial to Yugoslav underground artists in the 1980s.

Since the “whole socialist machine was aimed at neutralizing the side effects of a pertinent interpretation of its reality and of art production,“16 artists sought out alternative, yet unwritten histories without any “original” past. In this retro-avant-gardist universe, fiction replaces history. The act of copying is a key strategy used in late Yugoslav conceptual art. The artist Goran Đorđević, for example, reproduced and exhibited abstract paintings by Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich.

Laibach’s appropriation of fascist symbols, on the other hand, is an act of copying that can be described as “overidentification”,17 a term coined by Slavoj Žižek. Overidentification means to “over-affirm the dominant political and aesthetic conditions, ideologies, and structures […] in order to recognize them and deidentify from them.”18 Laibach’s art is not fascist because it uses fascist imagery; on the contrary, it uses fascist symbols to identify and overturn them.

Overidentification is not just a strategy for criticizing ideology. It reveals a deeper interest in temporalities. Parody, appropriation, and copying are practices of retranslating the past (and the future) into the present. Copies are semantically richer than the original: they allude to the original idea and the act of copying.19

In the same spirit, Gržinić and Šmid’s Cindy Sherman (1984) reconstructs Sherman’s photos as an act of overidentifying with the American artist that became world-famous – and commercially successful – for her play with different gender identities. The video was part of NSK’s project Back to the USA, an exhibition of reproductions of American art that were exhibited in Ljubljana’s ŠKUC gallery in 1984. Gržinić and Šmid stage postures and motifs from Sherman’s photographs, distorting the original images through acting and editing.

Their “copies” of Sherman’s photos are moving images that reanimate Sherman’s female subjects. Using Žižek’s term, their act of appropriation is both a negation of and an overidentification with Sherman’s originals. Also, as the artists point out, their “(re)possession” of Sherman’s photographs makes a “double turn”: yet another recycling of “the already recycled photographic images by Cindy Sherman [that] she takes from movies.”20 Sherman’s dead stills come to life again in Gržinić and Šmid’s visceral body-performances, with sweat and tears running down their motionless faces.

“A socialist parade is not only a solemn performance; it is also preparations involving the man condemned to death before he is taken to the scaffold. As if the final culmination of every parade were not the excitement it arouses but might just well be a body, embalmed, glazed and made up as a victim,” says the narrator in Bilocation (Bilokacija, 1990).

“Bilocation” is the miraculous ability of an object or body to be located in two different places at the same time. In Gržinić and Šmid’s video, it is a metaphor to capture the bloody history of Kosovo — marked by the conflict between ethnic Albanians and Serbians – which plunged into unrest in 1989. Documentary footage from TV Slovenia is juxtaposed with multiplied shots of a dancer dressed in red. Excerpts from Roland Barthes’ 1977 A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments are channeled through the voice-over.

The dancer’s body and found footage from Kosovo overlap and permeate each other, with images perforating her eyes, face, and intestines. The final socialist parade, Bilocation cynically suggests, are the coming bloody wars of its destruction. “When dressing up for the parade I am actually adorning my body which is soon to be destroyed by lust.” Like the Sherman video, Bilocation performs “the act of taking possession of documents, photographs, images, faces and bodies.”21

Bilocation concludes Gržinić and Šmid’s work of the 1980s, painting a dark vision of the decade to come. A bright red star adorns the disturbing collage. “It is not red, it is blood, is the indivisible post-Communist remainder that is not (yet?) possible to re-integrate into the global (media) world,” Gržinić was to write much later.22 Communism, Gržinić suggests, “is not red, it is blood.”23 And video is the territory impregnated with this blood, torn between history and the infinite loop of copies and fictions. There is no way back and no future.

References

- 1.A recent retrospective entitled “Marina Gržinić & Aina Šmid: Dissident Histories’’ ran at Loža Gallery, Koper (25.11.2022–28.02.2023). Thanks to Marina Gržinić who generously shared material and videos with me. Excerpts of her and Šmid’s work can be found on their website: http://grzinic-smid.si/?page_id=389 [Accessed on 25 October 2023].

- 2.http://grzinic-smid.si/?page_id=256 [Accessed on 25 October 2023].

- 3.Sally R Munt. Interview with Marina Gržinić (September 8, 2020). Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics 4(2), 31. https://www.lectitopublishing.nl/download/interview-with-marina-grzinic-8519.pdf; 6 [Accessed on 25 October 2023].

- 4.http://grzinic-smid.si/?p=306 [Accessed on 25 October 2023].

- 5.https://www.obalne-galerije.si/en/marina-grzinic-aina-smid-dissident-histories/ [Accessed on 25 October 2023].

- 6.Munt 2020, 6.

- 7.Gržinić, Marina. 2020. “VHS as a medium of subculture.’’ In: Sandra Frimmel, Tomáš Glanc, Sabine Hänsgen, Katalin Krasznahorkai, Nastasia Louveau, Dorota Sajewska, Sylvia Sasse (Ed.). 2020. Doing Performance Art History. Open Apparatus Book I.

- 8.http://grzinic-smid.si/?page_id=389 [Accessed on 25 October 2023].

- 9.Ljubica Spaskovska. The last Yugoslav generation: The rethinking of youth politics and cultures in late socialism, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017; 23.

- 10.Munt 2020, 4.

- 11.Munt 2020, 2.

- 12.Munt 2020, 3.

- 13.Quoted in Munt 2020, 4.

- 14.Dubravka Djurić and Miško Šuvaković (Ed.). Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-Gardes, Neo-avant-gardes, and Post-avant-gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918-199., Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003; xiv.

- 15.Marina Gržinić. Situated Contemporary Art Practices: Art, Theory and Activism from (the East of) Europe. Ljubljana/Frankfurt a.M.: ZRC Publishing/Revolver, 2004; 144.

- 16.Ibid.

- 17.Slavoj Žižek. Why Are Laibach and NSK not Fascists?. In: Zdenka Badovinac, Eda Čufer and Anthony Gardner (Ed.) NSK: From Kapital to Capital, An Event of the Final Decade of Yugoslavia, Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 2015; 202-204.

- 18.Badovinac et al. 2015, 8.

- 19.Marina Gržinić. Fiction Reconstructed: Eastern Europe, Post-Socialism & the Retro-Avantgarde. Vienna: springerin, 2000; 71.

- 20.http://grzinic-smid.si/?p=301– [Accessed on 25 October 2023].

- 21.Quote from http://grzinic-smid.si/?page_id=256 [Accessed on 25 October 2023].

- 22.Gržinić 2000, 36.

- 23.Quoted in Munt 2020, 6.

Leave a Comment