Scoring the Era of Upheaval

Rashid Nugmanov’s The Needle (Igla, 1988)

Vol. 157 (September 2025) by Nora Furlong

The first thing heard in Rashid Nugmanov’s 1988 film The Needle is a rattle, perhaps of a can kicked or blown by the bitter Almaty wind down an empty alley. Almost empty; a cat, introducing itself by a mew, traverses this backstreet, while a distant figure appears in the background. Although the individual is still indiscernible, the sudden voiceover must be referring to him, even if the narrator’s gravelly statement – “nikto ne znal kyda on idet” (“nobody knew where he was going”) – hints at his remaining unfathomable. The guy sure seems enigmatic, but chicly so, for as the voice continues – “i sam on tozhe” (“and neither did he”) – a beat begins, a syncopated intro evoking hip kids nibbling cigarettes. As the first verse of Russian rock band Kino’s “Zvezda Po Imeni Solntse” rings out, and as our punk protagonist approaches the camera, one might feel unsure if they are in the right alley. Is this Nugmanov’s directorial debut, one of the most celebrated and experimental films of the Kazakh New Wave? Or is this a music video for Kino, with all the formulaic features of a late 80s rock reel and an actor who looks an awful lot like the band’s lead singer, the lionized Viktor Tsoi? The question is moot. When Tsoi – both frontman and main character, Moro, in this case – reaches the foreground, the color scheme quickly switches to a more saturated, almost garish hue, and the modish music swells; concerns of who this nomad might be, and through what dilapidated city he moves, fade out. All that’s left is Kino’s indifferent croon: “On ne pomnit ni chinov, ni imyon / i sposoben dotyanut’sya do zvyozd” (“He doesn’t remember ranks nor names / and is capable of reaching towards the stars”).

Just like its protagonist – cool but ever uncategorizable – The Needle seems to at once play into and play against type. Critics have attempted to thread the needle; the feature has been deemed a “postmodern synthesis” of several cinematic cultures, uniting, as Ludmila Zebrina Pruner puts it, “the American western with the bytovoi (coming of age) film … a documentary with a musical.”1 It’s been hailed as an ode to Viktor Tsoi, the piece that put Kazakhfilm Studios on a momentary pedestal, and the bizarre brainchild between brothers Rashid and Murat Nugmanov (director and cinematographer). From its formidable success at the 1989 International Film Festival in Moscow, to its current cult status as an emblem of the chernukha genre – a neo-romantic and violent aesthetic phenomenon occurring during and arguably as a result of Gorbachev’s glasnost – Needle has maintained its image as an entertaining and elliptical example of late-stage Soviet cinema.

In situating the film, there are many elements which beget and beg comparisons to its contemporaries; like its perestroika-era peers, Nugmanov’s Needle gives a glimpse into the Soviet subculture of the 1980s and 90s, showcasing the sex (in communal apartments), drugs (supplied by the New Soviet “Narkoman”),2 and rock ‘n’ roll (Kino, Nautilus Pompilius, Aquarium, DDT). Because the Gorbachev administration’s glasnost policies emboldened artists to exhibit the “shameful lacunae” of the U.S.S.R. (albeit within reason), filmmakers were liberated from the “cinematic didactism” imposed by the decades-long governance of GOSKINO (State Committee for Motion Pictures), and could, ostensibly, toss the creative tradition of Socialist Realism to the dogs. Merging melodrama and “kitchen-sink cinema,” chernukha movies – from the Russian portmanteau for “dark reality” – depict the daily lives of the young, the immoral, and the hedonistic in an environment wherein the validity of Soviet doctrine was steadily seeping out, and Western culture was seen and heard more and more. They were by and for a “generation of Soviet youth, lost between the East and West, cynicism and romanticism,” seeking out an istina (truth) not written in Pravda and a type of spravedlivost’ (justice) not provided by the powers that were.3

In rejecting past practices of aesthetic apotheosis, the heretofore-ignored cynical underbelly of Soviet society was brought to light in all its gritty glory: working-class families, the criminal echelon, and bitter adolescents populate these decaying, but strangely winsome, landscapes. The films of this period illustrated a nihilistic and countercultural attitude towards life in the U.S.S.R., establishing the form and content of chernukha as an artistic formula for representing, finally, reality. Yet in seeking out a naturalistic portrayal of a dissolving and desperate Soviet Union, many of these movies established new types of (anti)heroes to fill the void left by the death of the Homo Sovieticus. Misery was at once unmasked and fetishized. Chernukha, as a “representational art that emphasizes the darkest, bleakest aspects of human life,” acted as a cinema of catharsis.4 Nonetheless, its revelatory elements became, in turn, romanticized.

Needle fits in – as the whimsical brother of Aleksei Balabanov’s Brother (Brat, 1997), the slightly less salacious contemporary to Vasili Pichul’s Little Vera (Malenkaya Vera, 1988), and the far less depressing coeval of Vladimir Lyubomudrov’s White Crows (Belie Voroni, 1988). Yet, while it is indisputably situated within the chernukha filmscape, certain elements in Needle’s portrayal of the immoral and abysmal state of the Soviet Union separate it from the grave and weighty aim of its aesthetic peers. Neither the glorification of Soviet society nor the ennobling of its nastier elements is as prevalent. Identifying the film as a glimpse into the moral void, as a postmodern pastiche begotten by political instability, or as just one ruin porno among many, ignores the important, impish otherness which gives Needle its edge. Its many classifications seem to only circumvent the film, an evasion practiced as early as 1990; critics writing about the Kazakh New Wave – of which Needle is considered the catalyst – chalked it up, in all caps, to a “DRUGOE KINO” (“DIFFERENT CINEMA”), calling it an unprecedented “phenomenon” from the Soviet republic of Kazakhstan.5

What, exactly, is so deafeningly different about Needle? The sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll of Soviet subculture are definitely present, portrayed with quintessential chernukh-ian candidness – such as when Moro (Tsoi), grinning easily, asks his drug-addled beloved Dina (Marina Smirnova) if her boss “tebya trakhaet?” (“he fucks you?”), or, more harrowingly, the scene in which Dina’s technique of shooting up is shown in all its disgusting sorrow. But the reproving “reality” exhibited by other chernukha archetypes is inconsistent with Needle’s. Its dark landscape – the dim peripheries of and around Almaty – is decidedly light; there is a distinct playfulness to the film, a flippant manner of worldbuilding which gives an impression of mischievous manipulation instead of malevolent criticism or post-heroic heroizing. Meaning is made and immediately cheerfully negated through Needle’s eccentric, indulgent, and self-aware form; it is as if a pofigzim narrative (a term derived from the Russian slang expression “po figu,” implying total indifference) took place in a circus. This is due to certain structural techniques, first wielded by Nugmanov in his short student film Ya-Ha (1986); a disruptive and disrupted diegesis, an almost “hallucinogenic” soundscape, and the constant, cartoonish juxtaposition of sound and image turn Needle into a film within a film, or a series of narratively related music videos, or a stylized, psychoactive experience with little interest in righteous revelation. Spravedlivost’ is far less essential, it seems, than which Kino song should play when.

As glib as that claim might be, Nugmanov himself made no fuss about Needle’s meaning; during a 1989 interview, the director stated that his piece is simply “about friends who are trying to play in film, that’s all. We just wanted to have fun.”6 I would argue that it is this “fun,” manifested most formidably in Needle’s experiments with the sonic structure of its narrative, that constitutes its DIFFERENce. Its treatment of sound at once distinguishes the film from its fellows and places them in conversation with each other. Nugmanov, like other directors of this period, took advantage of glasnost’s aesthetic unfettering to depict Soviet subculture, using the culture’s music – rock from both the republics and the West – as the score to this era of upheaval. But he also recognized and so heavily involved the extant purr of propaganda from various sources of Soviet popular media, especially television and radio programming, which failed to be drowned out by these punk anthems of progress. While political admonitions and animated voices can be heard in other films of this period– such as Kin-Dza-Dza! or Courier (both 1986) – the “schizophrenic mumblings” of Soviet broadcasts function as a surreal and omniscient spirit in the world of Needle, like some half-mad aunt watching you from her balcony. So although Nugmanov seemed to reject any notions of his movie as a symbolic exegesis of life in the Soviet Union – even unequivocally stating that he doesn’t “write about real life” – there is, within and around the soundscape of Needle, an acknowledgement of reality, absurd as the method of acknowledgment is. Through an oscillation between intradiegetic and extraneous sound, the two main components of the soundscape – sourced from mainstream media and the Soviet subculture of punks and gangsters – make Needle play out in a kind of ironic echo chamber. By including much of Kino’s oeuvre (and matching the band’s songs to Tsoi’s face), the hypnotic lilt of Soviet television programming, and the fragmented aurality of switching between radio platforms (with Kazakh, English, and French language stations momentarily heard), there results a fascinating and funny incoherence between worlds – between the tovarish-tabulated and televised perfection of what the Soviet Union appeared to be, and its destitute, destabilized reality.

This disjuncture is witnessed throughout The Needle, and from the jump. About three minutes into the film, over the last few chords of “Zvezda Po Imeni Solntse,” Moro steps into a phone booth to call his old girlfriend, Dina. He shouts into the barely functioning receiver that he’s just come from Moscow, inquires after her family, and cheerfully says he is broke. Upon hanging up the phone, he fishes out the coin, tied to a string, which he used to place the call. Against the image of this petty-bum trick plays a voiceover; dulcet tones tell us that we are now going to be told an “unfortunate story,” and that as we listen, we must “pay attention to the time.” The next shot obliges this condescending direction with a digital clock flashing a neon 9:00, and from there we are ferried along through the unfortunate story with the unceasing aid of these escorts: the punk ballads of Kino and the patronizing encouragements of Soviet programming.

We learn that Moro has come to Almaty to collect a debt, but upon finding Dina addicted to morphine and involved with some weirdos, he decides he must rescue her from these badlands. Before doing so, however, he has business to settle and arranges a meeting with Spartak (Aleksandr Bashirov), leader of the local drug pushers. The threat of a chaotic encounter is clear, but we are brought to this scene with the habitual gradation between shots; transition music plays, the lilting voice of the narrator sweetly tells one what to expect, and the digital clock strikes 19:35. At this point in the film – about twenty minutes in – the transition from space to space is well-established; between each scene, the audience is given a moment of metalepsis, this break of the fourth wall, as an unseen and disembodied narrator speaks directly to the viewer. In this instance, we are told that “it is time to go to a cafe” – preparing us for the next space – where “the guy who is always late will have an appointment with his friend” – preparing us for the next action, the standoff between Spartak and Tsoi. One might feel a bit babied; critic Michael Brashinsky aptly likens this “syrupy voice-over” to one belonging to “a children’s program a la ‘Sesame Street.’”7 Nugmanov’s use of these simplistic, mass-market television techniques divvies the narrative up in a sardonic and almost sentient manner; Moro’s movement through a thug-run and drug-fueled underworld is presented in a neat series, akin to how popular programming is offered, creating an absurd juxtaposition between the story and the candied clinicality of its structure.

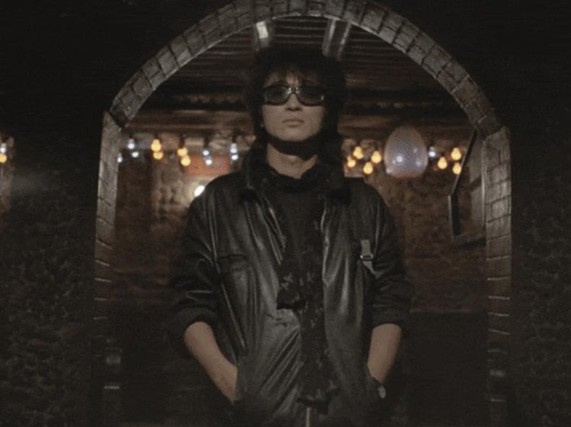

Entering the cafe, the background music of the transition becomes briefly diegetic, before Claudia Mori’s “Non succederà più” usurps it. Moro sips an espresso to the Italian pop song, casing the joint for potential saboteurs while lost love is lamented over the radio. The world of Needle seems to at once maintain and make fun of paradigms; since its soundscape offers, as put by critic Greg Dolgopolov, “an obvious, childish subtext to the action in a sonic form,” any depicted brutality, negativity, or even insouciance comes across as fatuously performative.8 As the camera moves between midshots of Moro and his perspective, a mafia clown enters and hands the barman a cassette. Edita Piekha begins to scat. The rest of the gang enters, and we see the sudden flare of carnival-like lights reflected in Moro’s glasses (Figure 1). Even though Spartak demands that the room clear, and a legion of goons take up their positions, there doesn’t seem to be anything to fear; we are in a fun house, a Cosa Nostra fabricated for the benefit of making Moro even more of a badass.

The casting of Viktor Tsoi as Needle’s enigmatic hellion adds to this waggish sonic division between the real, the glorified, and the glorification of the real. Tsoi, a rockstar and legend of the anti-establishment Soviet youth, was adored for his punk rock attitude and allegorical lyrics, and first worked with Nugmanov on Ya-Ha, a short documentary about the underground rock scene in 1986 St. Petersburg. It was around then that Kino, and Tsoi as its frontman, became ridiculously famous across the Soviet Union; “Kinomania” rocked the republics, and many of the band’s clever, incendiary songs became “romantic anthems of change.”9 The soundtrack of The Needle is primarily composed of such anthems, a choice which lays a playful membrane of irony over the movements of the main character. It is indulgent to watch Tsoi, an idolized representative of Soviet subculture, approach the camera, ever-present cigarette dangling from lips, while his own voice croons in the background. But the visual and aural experience is effective; the almost insolent relation between sound and structure, rocker and dissident allows the audience to revel in the simultaneous disjuncture between and layering of realities. Tsoi is the star of both an alternative Soviet stage and the weird world of The Needle.

A comparison to Brother’s Danila (Sergei Bodrov Jr.) may augment the self-aware strata of Tsoi’s role. The hoodlum protagonist of the 1997 film – which I would argue is the nec plus ultra of the chernukha genre – adores listening to Nautilus Pompilius, and the band’s music makes up a formidable part of The Brother’s soundtrack. NP accompanies Danila as he smokes in the begrimed streets of St. P, or, alternatively, as he kills Chechen mafia bosses, and the hitman has a practically puerile love for the tunes. Similar to Needle’s uplifting of Kino, Brother became one of the most commercially successful films in Russia and Nautilus Pompilius enjoyed not a small rise in popularity from their involvement. A type of trifecta seemed to have been hit on; a Russophile gangster film, with a great score, and a loveably tough lead played by a heartthrob. Danila is undoubtedly the ideal example of the chernukh-ian anti-hero; to replace the shiny idols of the past comes a still strong man with no ideological qualms, who values family and fraternity, but also McDonalds and rock music. Along with his criminal tendencies, Nautilus Pompilius marks Danila as a member of Soviet subculture (although the band was, by the late 90s, relatively mainstream). Yet despite the fact that NP was popular in and out of the reality of Brother, there is no potential of meta-irony in Danila’s partiality; the songs never make the actions of the anti-hero tongue-in-cheek. As for Tsoi, the situation is steeped in jest; he sings as his character swaggers and shoots, turning the world of Needle into an “extended music video.”10 Perhaps Nugmanov himself puts the paradoxical appeal of this coalescence best; “Moro is a kind of Romantic Hero. But Moro is Tsoi. The character … is Tsoi and his music.”

This sentiment is part of the crucial distinction that separates The Needle from other films of both its time and the chernukha genre; the sound of a subculture is a character in and of itself. Rather than being used as proof of the ontological authenticity of the reality portrayed, rock music is incarnated as Moro. But he in turn is a mask for Tsoi, a facet that asks the viewer/listener of Needle to engage in a benign type of doublethink; we are able to experience two manifestations of the man at once, one of which acts out the countercultural persona (as created by Kino’s music) of the other. It is difficult to know whether it is Moro who glorifies Tsoi or vice versa. But the playful nature of the performance is indisputable.

The cacophony of the landscape through which this embodied rocker moves is the other part of Needle’s distinction. As alluded to before, there is a near-constant aural subtext, which overlaps, clashes against, or curiously conforms to the action on screen. There is rarely a moment of quiet, even when the lovebirds escape to the desert; Moro, like some knight in leather armor, rescues Dina from her circle of addicts, and they play house in the arid wasteland which used to be the Aral Sea. In a rudimentary stone dwelling, Dina goes cold turkey and Moro rolls cigarettes between chores. Over a montage of her withdrawal, discordant, almost tribal disco chords play from somewhere while Dina writhes around. A snatch of Uzbek is heard, when an old sage blows in out of nowhere. There is a shot reminiscent of that worm-cam one in Lynch’s Blue Velvet, and scorpions momentarily add their clicking to the symphony. This incessant and unfiltered diegetic noise is important in the world of and around The Needle, important for how the film is understood and how it understands itself. Qualms about both the misery depicted and the meaning of this depiction are overwhelmed by the veritable din of the soundscape, which some might contend is a result of Nugmanov’s aimless, cinematic naturalism. But the reality of life in the late-stage Soviet Union, at least the reality aimed for by other chernukha films, is not just made up of the sound of a muffled gun and a raspy rock song. Nugmanov inundates Needle with a surplus of sound sourced from, as outlined before, several realms of reality: Soviet subculture, Soviet popular programming, and music from an international sphere. While some may say this racket reduces the intelligibility of the film, the sonic fidelity is crucial. Here, I would steal a question posed by critic David MacFayden in his analysis of the “Russian ‘Rockumentary,’” wherein he explores discordant film scores; “is this homeless excess closer to actuality?”11

Whatever the relation to the real, The Needle, because of its at once lifelike treatment and superficial warp of sound, stands apart. The playful detachment with which Nugmanov treats the less-than-pleasant aspects of reality has been explained in several ways. Perhaps the fact of the film originating from the “peripheral Soviet Union,” from, as Nugmanov put it, the “nomadic nature” of Kazakhstan, contributes to this cinematic distance. But I would feel remiss to explain Needle’s DIFFERENT components as such, for fear of implying that anything NON-RUSSIAN is that which diverges. As alluded to, and as expressed by Nugmanov himself, Needle was a result of “playing in filmmaking,” a statement to which many of the formal idiosyncrasies of the film can be attributed.12 It seems to correspond to chernukha in terms of themes, and while the grittiness of an alternative milieu is still communicated by Nugmanov, the stakes are not so high. Instead of examining the social, political, and cultural environment through filmmaking, Needle seems more inclined to focus on film and soundmaking themselves, approaching these landscapes by way of music and other forms of media. The film is therefore witnessed through various sieves of cultural and technological illusion, resulting in a “delusional world,” wherein “anything is plausible because cultural symbols have lost their power, authority is decaying and nothing is so serious…”13

Needle’s form manipulates the misery of its world, portraying it playfully within a construction more evocative of cultural expressions than social strife. A bleak, “somnambulistic fog” engendered by drugs and general malaise hovers over the landscape, but that which cuts through the mist – punk music, popular programming– mocks the meaning of this environment, rejecting the rational and favoring the absurd. The sharpened point of Needle often provides an ironic prick, despite the harrowing representation of addiction and violence. Not to say the prick is painless; after returning to Almaty, Dina quickly relapses, the thugs pursue Moro with purpose, and several deaths occur. In an awful and awfully stylized penultimate shot, one of Spartak’s minions approaches Moro in the snow-filled street, asking for a light. The man stabs Moro, holding his wrist so he can still light the cigarette. As Tsoi’s voice sings, his character smiles bitterly and stumbles towards the horizon, and one feels a romantic ache for the hero of this underworld. A lament is ultimately what’s left when Needle ends; as Moro pitches into the night, Tsoi performs “pozhelai mne: ne ostatsya v etoi trave, ne ostatsya v etoi trave…” (“Wish me luck, I won’t stay in this field of green, won’t stay in this field of green…”)

- Prener, L. Z. (1992). The new wave in Kazakh cinema. Slavic Review, 51(4), 792. ↩︎

- Conroy, M. S. (1990). Abuse of drugs other than alcohol and tobacco in the Soviet Union. Soviet Studies, 42(3), 447–480. ↩︎

- Brashinsky, M., & Horton, A. (1994). Russian critics on the cinema of glasnost. Cambridge University Press, p. 124. ↩︎

- Brashinsky & Horton, 1994, p. 124. ↩︎

- Shpagin, A. (1990). Novaia volna?! Iskusstvo kino, 9, 65–69; Aprymov, S. (1990). Naperekor mifu. Iskusstvo kino, 9, 70–72; Zarkhi, N. (1990). Drugoe kino. Iskusstvo kino, 9, 72–75. ↩︎

- Horton, A. (1990). Nomad from Kazakhstan: An interview with Rashid Nugmanov. Film Criticism, 14(2), 36. ↩︎

- Brashinsky & Horton, 1994, p. 124. ↩︎

- Dolgopolov, G. (2010). Igla (The Needle). Senses of Cinema, 55, 57. ↩︎

- Dolgopolov, 2010, p. 54. ↩︎

- Dolgopolov, 2010, p. 54. ↩︎

- MacFayden, D. (2010). The Russian ‘rockumentary’: Documentary films and rock, pop, and chanson. The Russian Review, 69(4), 671. ↩︎

- Brashinsky & Horton, 1994, p. 125. ↩︎

- Brashinsky & Horton, 1994, p. 53. ↩︎

A beautifully written and insightful critique. Where can we see the film?

There is a version on YouTube in a decent quality:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=uOVZjX3UpMk&pp=ygUNSWdsYSBudWdtYW5vdg%3D%3D

Hope it works!