Last month, as the Berlinale kicked off, we wrote about the working conditions at the event and European-wide initiatives to improve the terms of employment of film festival employees. While the working conditions of festival workers remain precarious for a majority of employees, precarity disproportionally affects female employees. As the next big film festival is approaching, the issue of gender equality in the industry has once again made headlines. As reported by the collectif 50/50, a publicly funded collective promoting gender parity in the French film industry, only the Semaine de la Critique selected as many films directed by female as male directors in the orbit of this year’s Cannes film festival, which is traditionally accompanied by parallel events like the Semaine or the Quinzaine des Cinéastes.

The European film industry still has a long way to go in achieving gender equality. Despite various commitments by festivals, funding bodies, and industry associations to address the gender gap, a recent industry report reveals just how tall the order is. The report, published by the European Audiovisual Observatory (EAO), conducted a survey of crews involved in European feature films produced and released between 2016 and 2020. It found that women represented only 23 percent of all directors. Behind the scenes, women accounted for slightly over one-third (33 percent) of working producers and just under one-third (27 percent) of screenwriters. The gender disparity is particularly pronounced among cinematographers and film composers, with women comprising only 9 percent and 10 percent of active professionals respectively. For cinematographers, a divide between Eastern and Western Europe can also be observed, with women being even more underrepresented among Eastern European cinematographers. On the other hand, the share of female producers turns out to be above the European average in Eastern Europe. In Romania, the share of female producers is even slightly above 50 percent.

Even on screen, there is a significant imbalance, as women only account for 39 percent of lead roles in European films during the five-year period analyzed. Compared to regular features, the presence of female directors is relatively higher in documentary films, where women make up 29 percent of directors, compared to 19 percent for live-action fiction films and 16 percent for animated features. These findings should serve as a wake-up call, considering the publicized efforts in Europe to achieve a 50/50 gender balance among filmmakers. They also provide ammunition for those advocating for more proactive measures, such as gender quotas for film financing.

As recently as 2021, several highly acclaimed European films were indeed driven by female talent, including Titane, directed by Julia Ducournau, winner of the Palme d’Or; I’m Your Man by Maria Schrader, a German Oscar contender; and Happening, an abortion drama by Audrey Diwan, which won the Golden Lion for Best Film at the Venice Film Festival. Quo Vadis, Aida?, directed by Jasmila Žbanić from Bosnia, a film centered around the Srebrenica massacre, received multiple honors at the 2021 European Film Awards, including the prizes for Best Film, Best Director, and the award for Best Actress, which went to Jasna Đuričić. Many major European film festivals have also committed themselves to achieving gender parity by signing pledges, aiming for a 50/50 balance between male and female directors in their official selections.

Of course, gender discrimination may be yet more entrenched than quotas can reflect. It is harder to blind the male gaze than to make people see the gender of a director. In one perverse scenario, films directed by women will be shown and win prizes alongside those directed by men, but the choice of the selected films and motive behind their accolades, may yet continue to be driven by dominance and humiliation. It is also harder to see the male gaze than the gender of a director. Especially when it imposes itself on us and, weakened by its force, we come to internalize it and accept its terms without ever being quite aware of how exactly it managed to shape our psyche. Remembering the queer cinema of the 1990s, Todd Haynes, in a recent masterclass given at the Centre Pompidou, recalls how filmmakers pursued a strategy where “the point was not a claim a seat at the table, but to question the table and to reverse it.” In that sense, gender equality may not be achieved, even if the numbers said otherwise, so long as the norms of the gatekeepers of cultural participation are not put into question.

***

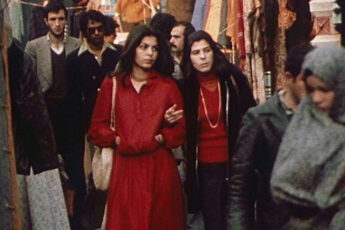

This month, we continue our coverage of the Berlinale. Zoe Aiano revisited György Fehér’s 1990 Twilight, a film reminiscent of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, while Anna Doyle reviewed Vlad Petri’s Between Revolutions, a fictionalized account of the friendship between two young women who lived through times of political turmoil in Iran and Romania. Jack Page has launched his coverage of the Crossing Europe film festival in Linz, where he saw Dominik Mencej’s Riders, a Slovenian buddy road trip movie; Irma Pužauskaitė’s The 9th Step, a film on life with and after addiction; and Vitaly Mansky and Yevhen Titarenko’s Eastern Front, which documents life on the front in Ukraine from the perspective of a paramedic. Finally, Antonis Lagarias discusses Alexander Sokurov’s Fairytale, which takes the political protagonists of WWII to the gates of heaven.

We hope you enjoy our reads.

Konstanty Kuzma & Moritz Pfeifer

Editors

Leave a Comment