In Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy, editing is used to make Batman (Christian Bale) vanish on command. In The Dark Knight (2008), Batman talks with Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart) and Police Commissioner James Gordon (Gary Oldman) on a rooftop; the camera stays on Dent as he turns his head mid-conversation, and the next cut shows him facing the same spot, with Batman gone. The film never shows the exit, so the viewer reads it as a sign of extreme stealth and speed. The missing “walk away” moment preserves Batman’s mythic omnipresence and becomes a running joke. Gordon, already used to the stunt, ends the scene saying, “he does that.”

In Hollywood movies and popular TV series, most characters act like Batman. Although they let each other finish their sentences, if only barely, the editing is so fast that the camera often cuts away a beat before a line ends, shifting to the listener’s face or a new angle to keep the dialogue punching forward, a technique David Bordwell has described as part of “intensified continuity.” The voice still completes the thought, but the cut steals the pause that would normally let it breathe. The same effect pairs with constant shifts of setting, so characters seem to talk across a stream of new rooms, environments, and micro-moments, with no time for a scene to sit still. The extreme use of such techniques in film, usually known as “post-continuity,” of course resembles the grammar of social media, in which our attention is trained to expect the next image before the current one has fully resolved.

Perhaps as a reaction to this, some films are increasingly embracing flânerie as a refusal of the cut, insisting instead on the time it takes to leave. Filmmakers seem to believe that if we don’t see the character find their keys, open the apartment door, close it, lock it, walk down the stairs, open the front door, close it, walk down the street, take a left, take a right, and another left, the character basically doesn’t exist or, worse yet, has superpowers like Batman.

In Dea Kulumbegashvili’s April (2024), Nina drives across the Georgian countryside, between medical appointments. The scenes are as long, and sometimes longer, than the appointments. Minutes pass as the road stretches across the Georgian plains and the car moves through the grass and the gray light. The viewer sees the steering wheel, the passing trees, and the long curves of the highway. While the director undoubtedly wants to establish a connection between her protagonist and the environment, the connection is prolonged with so much naturalism that Nina ends up vanishing. Batman would be proud.

This kind of flânerie is not restricted to European arthouse films of the periphery or so-called “slow cinema.” Recent movies like Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Secret Agent (2025), Nathalie Najem’s No Way Back (2025), or Christian Petzold’s Mirrors No. 3 (2025), all have their protagonists drift between scenes as if they were in a state of perpetual transit. In fact, walking does not play any narrative role in these movies, as they would, say, in a road movie or more existentialist films that depict their characters walking aimlessly and where, in short, walking could be interpreted as an essential part of cinematographic storytelling. No, in these films the point just seems to be to make a realistic gesture, a kind of realness signifier that helps perform the director’s commitment to reality even when that reality carries little or no meaning.

Early 20th century writers portrayed the flâneur’s leisure as a rejection of functional time and rational purpose. The flâneur walks, looks, lingers, and treats the street as a text that is to be read at human speed, while modernity tries to yank their gaze away with flashy posters and blinking storefront signs. In Franz Hessel’s 1929, Walking in Berlin: A Flaneur in the Capital, the narrator observes: “Around here, you have to have purpose, otherwise you’re not allowed. Here, you don’t walk, you walk somewhere. It’s not easy for the likes of me.” In a way, the long walks in contemporary European films resemble this passive resistance. They insist on the unproductive minutes that mainstream cinema edits out, as if the only remaining freedom is to waste time. The gesture comes with a form of self-congratulatory stubbornness: the more the films insist on showing the walk, the more it begins to look like a credential, a performance that the director has not been contaminated by hyper-fast editing.

However, where the flâneur rejected modern life on his own terms, there might be something else dictating the tempo of this new-found flânerie. After all, festivals like long films, programmers like “serious” films, and a director who can stretch a premise across two and a half hours looks, on paper, like someone worth funding. Some of these cinematic walks, then, may simply be driven by the pressure to meet a demand for feature-length runtime, even when a short or medium-length film could have done a better job, and when there is no viable infrastructure to support these formats.

The flâneur was never a hero to the city. As the only passerby who did not display a discernible purpose in their meandering walks, they were socially illegible, tolerated at best, an idle nuisance at worst. Does today’s independent and arthouse economy want films to perform this kind of flânerie? The real question, it seems, is not whether filmmakers have become afraid of the cut, but whether the institutions that validate them have become afraid that they might arrive somewhere. It is a form of institutionalized anti-heroism, a false sign of resistance. Where mainstream characters vanish because the edit will not let them exist between scenes, these characters vanish because the system will not let them exist anywhere else.

***

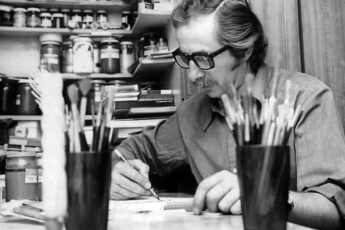

At DOK Leipzig, Zoe Aiano saw Urszula Morga and Bartosz Mikołajczyk’s Signs of Mr. Plum, a biopic about a Polish graphic designer that is neither particularly critical nor overly offensive. Daniel Schwartz offers a reckoning with the recent trend of AI-assisted films through his critique of Arthur Franck’s The Helsinki Effect, a trite and ultimately reductive story about how the Berlin Wall came crashing down. From the Thessaloniki International Film Festival, Savina Petkova reports with a review of Emine Emel Balcı’s I’m Here, I’m Fine about a misunderstood woman who finds purpose in female solidarity. Anna Batori discusses Bálint Szimler’s Lessons Learned, which portrays the Hungarian school system and the way that it reflects greater societal tendencies. Finally, Jack Page reviews When the Phone Rang by Iva Radivojević, in which a young girl leaves behind her home and with it part of her identity.

We hope you enjoy our reads.

Konstanty Kuzma & Moritz Pfeifer

Editors

Note: Due to delays in our publication schedule, this issue was published in the month of February 2026.

Leave a Comment