Living Patterns

Focus on Dóra Maurer at Fracto Film Festival

Vol. 159 (November 2025) by Mariya Nikiforova

The 2025 edition of the experimental film festival Fracto, which took place in May at the Kunsthaus ACUD in Berlin, featured a two-day focus on the films of visual artist Dóra Maurer (b. 1937, Budapest). The mini-retrospective comprised films Maurer made between 1973 and 1990 at the legendary Béla Balázs Studio. The program was curated by Federico Rossin, who had already presented a selection of Hungarian neo-avant-garde films at the festival Les États Généraux du Film Documentaire in Lussas (France) in 2021.

The focus on Dóra Maurer’s films was noteworthy for a number of reasons. To begin with, while this may seem surprising, an invisible line separates the milieu of experimental cinema from that of visual and performance artists working with the moving image. This division is due to many factors, including differences in modes of production and forms of institutional support, divergent ideas about proper presentation conditions and contexts, as well as questions of histories, lineages, and influences. At the same time, the mutual influence of the two fields is indisputable, and so it is always stimulating to see them presented in dialogue with each other. Furthermore, avantgarde practices from Eastern Europe of the Socialist period remain little known not only in the West, but often, in the home countries themselves. And they certainly do merit being rediscovered – both for their remarkable and sometimes off-the-wall contributions to conceptual and other artistic thought and, perhaps even more importantly in the current political context, for their experience with forging informal collective initiatives and networks based on mutual aid and solidarity. Finally, it is high time that Dóra Maurer be duly recognized for her remarkable body of work and for the clarity and consistency of her vision across multiple disciplines.

Maurer’s films thrive on a finely tuned tension. When she appears in her films with her signature middle-parted chignon and slick black outfits, she exudes cool minimalist reserve. The same calculated attitude defines the works themselves: she sets up a framework or a protocol and patiently carries out the steps. Yet, every time, the diegetic event (the captured ‘reality’) escapes the algorithm, however subtly, creating a moment of illuminated amusement for the viewer. Where does the protocol begin to slip, and why is it so moving?

Having studied in the graphic arts program at the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts in 1955–1961, Maurer arrived to film via printmaking. Over the course of the 1960s, as she struggled to find her place in Hungary’s officially sanctioned art scene, she privately progressed in her experimentation with “minimal shifts” and “displacements” of printed forms, gradually arriving at a “conceptualization” of her discipline that was intuitively in sync with global artistic trends of the decade.1 The translations she undertook during these years reveal her influences: Josef Albers’s Interaction of Color (1963) and Serialist composer Anton Webern’s The Path to the New Music (1963). Like conceptual artists in other parts of the world, she became interested in repetition and systems, and, like them, she would go on to bring process, labor, and daily life to the foreground of her work.

Though cut off from the West, Hungary experienced a political thaw in the 1960s and 1970s marked by greater cultural and transborder openness. In 1967, Maurer traveled to Vienna for a half-year residency, where she met the Hungarian émigré Tibor Gáyor, who would become her life partner and collaborator on many artistic and organizational projects. Together, they would split time between Vienna and Budapest, benefiting from a privileged access to artistic milieus in Austria, Germany, and Europe more widely speaking, all the while participating in the underground artistic scene that was beginning to take root in Hungary at the end of the decade.

In 1973, Maurer became a member of the Béla Balász Studio, where she could put into practice filmic ideas she had been pondering for several years. The studio had been launched in 1959 and officially established in 1961 as a space that would provide emerging filmmakers with the technical means to elaborate their first independent film projects. As a ‘concession’ to the youth after the suppression of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising, the studio was self-governed, allowing filmmakers to avoid governmental oversight; censorship intervened only after a film’s completion, at the stage of distribution.2 Thus, the studio became a center for cinematographic experimentation, especially after 1973, when filmmaker Gábor Bódy and art historian László Beke launched the Film Language Series, a discussion and screening format intended to stimulate interactions between semiotics, conceptual art, and film practice.

The first film of Maurer’s in the Fracto program, Learned Spontaneous Movements (Megtanult önkéntelen mozgások, 9’15”), was made in the same year, 1973. A young woman (artist Éva Büchmüller) contemplates an open book with girlish absent-mindedness (chewing a fingernail, then twirling her hair) while an off-screen female voice reads a passage from a fairy tale. The scene appears naturalistic, but, perplexingly, it breaks off mid-sentence and starts over again, with the same lackadaisical gestures repeated almost exactly as before. The action is replayed several more times before the voice begins to be layered cacophonously; during all this time, the woman repeats her deceptively nonchalant gestures again and again. The various takes are overlaid in positive and negative, presumably through the use of an optical printer, sometimes matching nearly perfectly, at other times forming doubles of the woman’s figure. Finally, four takes are placed side-by-side, creating a strange choreography of boredom.

The proximity of the Austrian experimental film scene, and especially its Structural vein pioneered by Peter Kubelka at the end of the 1950s, who also drew his initial inspiration from Serialism in music, must have had an impact on Maurer’s entrance into filmmaking, whether directly or indirectly. Like a full score spelled out in musical notation, Learned Spontaneous Movements is structured around repetition and variation. An exercise of sorts, it announces many of the preoccupations that Maurer would continue to explore in subsequent films: protocol and iteration, shifting and phases – but also, in a way that brings it closer to the work of the Austrian feminist performance artist Valie Export, body language and women’s (self-) representation.

Relative Swingings (Relativ lengések, 1973, 10’17”), undertaken around the same time, is a deceptively simple game exploring notions of perception and artistic process. Two simultaneously-shot sequences appear on the screen side-by-side: one filmed with an “active camera” and the other with a “passive” one.3 The “active” camera records two simple objects, a conical hanging lamp and a cylinder, as they are set in motion, while the “passive” camera, located a few meters away, films Maurer and the cinematographer János Gulyás over the course of the same action. The “passive” camera thus reveals that the apparent motion in the “active” sequence is created by swinging the camera, not the object. Like in the previous film, Maurer sets up a series of variations (only the camera swings, only the object swings, both of them swing, etc.), each time placing side-by-side the perceived motion and the filming process. The juxtaposition is surprisingly amusing and even touching. Like in some examples of video art made around the same time (such as that of Joan Jonas or Peter Campus), there is a curious ambivalence between the rigorousness of the protocol driving the work and the unadorned documentation of the artist’s process, a kind of self-portrait in action that also makes its way into the piece. Seen over 50 years after its creation, it is also a precious record of the Béla Balázs Studio’s artistic environment at that time.

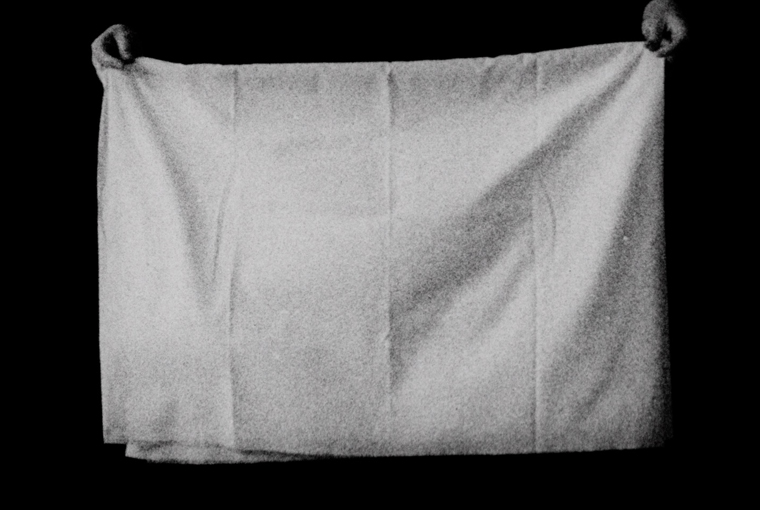

Perhaps one of Maurer’s better-known works, Timing (Idömérés, 1973–1980, 10’07”), was originally conceived as a live performance. In the film, the artist’s hands hold up and then fold a white tablecloth against a stark black background. After seven repetitions, the variations begin: the screen is now split down the middle with a different take of the action on each side. The two sides begin in perfect symmetry but inevitably shift out of phase due to the stochastic nature of the process. Going further, the screen splits into four rectangles (each rectangle filled with a different quarter of a take), and later, eight. Thus, the image is ‘folded’ through optical tricks just as the tablecloth is literally folded in the pro-filmic action. The choice of the object does not seem insignificant: a homely tablecloth, handled with the familiar gestures that evoke ‘women’s’ work, is here elevated to the status of an art object, breaking the division between everyday life and creative process.

Indeed, in presenting the program, the curator Federico Rossin insisted on the surreptitiously feminist slant of some of Maurer’s films, despite her own distancing of her work from any such political engagement. In seeing Proportions (Arásnyok, 1979, 10’22”), one would tend to agree with Rossin. In this video piece, she places a long roll of paper on the floor, with which she proceeds to take measurements of herself in order to demonstrate, absurdly, the proportion of different parts of her body (feet, hands, arms, shins, shoulders) in relation to her height. It is the Vitruvian Man as a woman, on video.

Maurer also appears on screen in her following work, Triolets (Triolák, 1980–1981, 10’40”). In this disorienting film, images shot in her studio are split into three lateral sections, which go out of phase as the three cameras pan back and forth at various speeds in an automatic manner that recalls some of Michael Snow’s works, such as Back and Forth (1969). Each camera is accompanied by a corresponding singing voice, which joins the two others in dissonant trios. Maurer herself is seen moving through the space, closing the window, and looking at the camera. The final sequence combines the middle section of her face with the top and bottom of the countenance of a mustachioed man. Again, the artist’s (female) body creates a point of interrogation within a piece that seems to be structured according to a predetermined pattern of action. The film is credited as being part of the experimental K/3 program that had been formed at the Béla Bálazs Studio in 1976 as a continuation of the Film Language Series.

If it might seem that Maurer’s filmography rests entirely on performed actions, Kalah (1980, 9’49”) is a totally abstract piece using rapidly changing rectangles of pure color and synthesized music. Although it certainly recalls some of the color flicker films by Paul Sharits, Maurer’s film stays true to her interest in Serialism, as the color blocks in Kalah are arranged according to variations derived from the eponymous board game. This work is closer to Maurer’s activity as a painter; in addition to creating abstract color paintings, she has also worked on color installations, such as a room environment she created at the Austrian Kunstraum Buchberg in 1983.

The following day’s program featured a bombshell of a film, Seven Trials (Hétpróba, 1981–1982, 55’40”). An experimental documentary shot in the style of television interviews, it involves five members of the same family (a mother, adult twin sisters, an adolescent sister, and a young brother) as they are questioned by Maurer on various issues, including deeply personal histories, and compelled to carry out certain actions as the camera attentively observes their body language. Again, Maurer is interested in repetition and variation, but in this case, it is the psychology and gesturality of the family members – who greatly resemble each other physically – that she seeks to analyze and compare. Like her previous films, but on a different scale and with different stakes, Seven Trials starts from a protocol, or even a hypothesis: the five participants are made to answer the same questions and carry out the same actions as if to demonstrate their genetic, or mutually acquired, predeterminations. The comparisons are emphasized by her use of superimpositions and a split screen. However, the entangled and sometimes painful history of the family and the strong personalities of each member repeatedly subvert the rigid framework of the interviews. As the film goes deeper into each of their subjectivities, it paints a complex portrait of a family through issues of shared trauma, gender performativity, and identity.

Never seen on the screen, Maurer remains a constant presence with her questioning voice, which she layers cacophonously over the voices of her protagonists in the last section, further implicating herself as an invisible subject of the film. One cannot help but feel troubled by the authoritarian tone in the artist’s voice and the veiled cruelty of her instructions (as when she tricks them into eating toothpaste). The result is open to interpretation, but, in view of its resemblance to a psychological experiment, it is perhaps her response to the concept of the “cognitive film” formulated by Maurer’s friend and fellow artist Miklós Erdély, through which he aimed to use the film medium to represent the structure of human consciousness in all its complexity.4

The three-part film closing the program, Inter-Images 1-3 (1989–1990, 17’28”), shows a departure in Maurer’s film language. Shot in color, all three parts of the film are concerned with visual perception as far as it allows to recompose a splintered image, and thus, with the foundations of cinema itself. The artist’s process is no longer depicted within the work, the production quality is slicker than previously, and Maurer’s interest in the body has shifted away from questions of self-representation and femininity. In “Retardation,” the first part, several film frames of a woman’s face unfold in extreme slow-motion as they are broken up into many small squares that flicker on the screen in apparently random order accompanied by synthesized tones. “Streams of Balance” portrays a male dancer filmed in close-up with a constantly moving camera, abstracting his body in motion in an estranging way that recalls the disorienting self-portraits of John Coplans. “Anti-Zoetrope” portrays two male boxers filmed inside a cylindrical space enclosed by a wall with vertical slits. The camera moves in a circle around the wall, capturing slivers of the action happening inside. As suggested by the title, the movement is recomposed from fragments in a similar way to the zoetrope, the famous predecessor of cinema.

Throughout her career, Dóra Maurer has not only continued to engage with many disciplines in addition to film (performance, photography, printmaking, painting), but has also been active as a curator and pedagogue. During the Socialist era, she actively used her connections on either side of the Iron Curtain to help promote Hungarian artists outside of the country as well as to bring Western European artists, filmmakers, and curators to Budapest. In 1975, she created an experimental artmaking course alongside Miklós Erdély that emphasized collectivity and interactivity over individual mastery. Throughout these activities, she continued to experiment, to push forward, and to support artists and students in her entourage. With an exhibition at the Tate Modern in 2019, Maurer has been receiving much-deserved attention outside of Hungary. Federico Rossin’s Fracto program contributes to reigniting interest in her films, proving that it is increasingly being recognized independently of the rest of her artistic practice. As any œuvre of truly timeless value, Maurer’s work stays true to itself as it never ceases to evolve and open itself up to endless new interpretations.

- Féher, D. (2019). Planes in motion: Hidden structures. In J. Bingham (Ed.), Dóra Maurer (pp. 70–89). London: Tate Modern, p. 70; Morris, F. (2019). Introduction. In J. Bingham (Ed.), Dóra Maurer (pp. 6–8). London: Tate Modern, p. 6. ↩︎

- Gurshtein, K. (2022). Conceptual artist, cognitive film: Miklós Erdély at the Balázs Béla Studio. In K. Gurshtein & S. Simonyi (Eds.), Experimental cinemas in state-socialist Eastern Europe (pp. 265–292). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 268–269. ↩︎

- Whitefield, C. (2019). Expanded thinking: Moving images 1970–1997. In J. Bingham (Ed.), Dóra Maurer (pp. 47–69). London: Tate Modern, p. 48. ↩︎

- Gurshtein (2022, p. 275). ↩︎

Leave a Comment