Ghosts in the Cold War Machine

Arthur Franck’s The Helsinki Effect (2025)

Vol. 161 (January 2026) by Daniel Schwartz

Arthur Franck’s The Helsinki Effect is an ordinary documentary. That is about the best thing one can say for it. It feels strangely from another epoch, when liberal bromides about the powers of a free press were consumed without question. It belongs to the era of cable in the classroom, with a framed photo of George H.W. Bush sitting atop the TV set. Save for two important differences. The film premiered in 2025 at the venerable CPH:DOX film festival and was made using generative AI.

The playful (but in fact rather boring) use of AI is the main selling point of Franck’s film. It tells the story of an important yet largely forgotten diplomatic summit held in Finland in the summer of 1975 aimed at easing Cold War tensions that resulted in the so-called Helsinki Accords. In exchange for territorial guarantees legitimizing its control over Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union promised to loosen restrictions on speech and expand civil liberties. This led to the creation of Helsinki Watch — later to become Human Rights Watch — an NGO that sought to verify compliance with the accords. If the film’s thesis is to be believed, the seemingly minor advances of the accords eventually led to the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Like the wings of a butterfly, the accords brought about momentous change from the seemingly insignificant flapping of diplomatic mouths.

Reference to the butterfly effect communicates the film’s crude understanding of historical temporality and aligns curiously with its use of AI. Both are products of cybernetic discourse. The butterfly effect was initially articulated by the mathematician and meteorologist Edward Norton Lorenz to describe how small changes in the initial conditions of a system could lead to drastically different results. A single flap of a butterfly’s wings could change the course of a future tornado. Such modeling of cause and effect in weather systems soon became part of a popular representation of the unintended consequences of time travel.

There’s no reason, however, to think that historical events — summits, accords, wars — interact with one another the way electrons or weather systems do. For want of a nail, a kingdom may be lost; but there’s no way to trace the loss of a kingdom to the loss of a nail. Poetic as the idea may seem, it does not make for a good archival documentary. The film’s narrator seems to understand this. He is constantly excusing himself lest the viewer find the material “too boring.” He wonders how to present archival footage of a diplomatic summit most viewers have either forgotten or are too young to recall. A noble task. But like so many writers and artists lost in the weeds, he makes a fatal mistake. He turns to AI for answers.

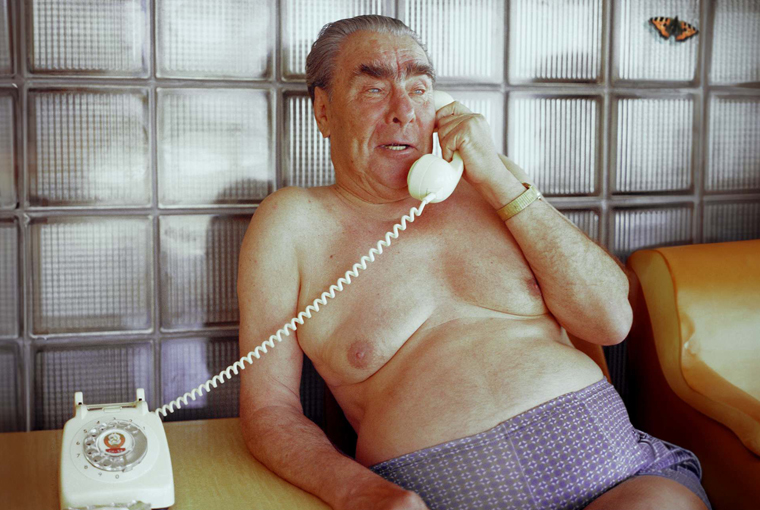

The move is somewhat cheap. Lacking an innovative way of putting the footage together, the film uses AI to embody the voices of the conference’s main participants: Henry Kissinger and Leonid Brezhnev. Kissinger and Brezhnev read from meeting minutes and telephone transcripts, giving voice to the off-scene (and at times obscene) details of history. Kissinger-AI has little trouble rendering the diplomat’s English cadence. Brezhnev-AI, however, has some difficulty given that the Soviet leader did not speak English. The narrator, in turn, interacts with both AI voices, asking them ironic questions and interjecting with witty remarks, much in the same way one would when having a conversation with ChatGPT.

The results are about as dull as listening to an actual broadcast of Brezhnev addressing the Soviet public on New Year’s Eve, perhaps more so, since the Brezhnev broadcast at least has some entertainment value. Nevertheless, there is something to be learned from this attempt to enliven history. The desire to get closer to historical personages and processes using the voice is an impulse shared by many recent documentaries, notably Morgan Neville’s Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain (2021) and Andrew Rossi’s The Andy Warhol Diaries (2022). These exercises in AI ventriloquism connect to larger anxieties about the voice as a source of alienation.

As Mladen Dolar channeling Slavoj Žižek points out, we all suffer from the fear that we are in a sense ventriloquized puppets.1 For Žižek, an “unbridgeable gap separates forever a human body from ‘its’ voice. The voice displays a spectral autonomy, it never quite belongs to the body we see, so that even when we see a living person talking, there is always a minimum of ventriloquism at work.”2 One can never be 100% sure one isn’t talking to a robot. This makes it possible to associate the acousmatic mystery of the voice with a mainstay of Lacanian psychoanalysis, l’objet petit a, the leftover remainder of desire that keeps it in motion – e.g. the feeling of never being truly satisfied. In ventriloquizing AI documentaries such as Franck’s, the desire to uncover the source of the voice is displaced onto history. One seeks in the spoken words of world leaders some magical formula that explains why things are the way they are. What one finds, however, are the same platitudes committed to paper by journalists reporting the events, along with a bit more small talk and a few extra dirty jokes. Having a conversation with a historical figure turns out to be not all that enlightening.

The most interesting feature of The Helsinki Effect is how the cybernetic view of history and that of the ghost in the machine come together in the immaterial voice of power. There is a desire to hear these world-historical leaders say what they’re actual thinking, to have something like an authentic conversation with them. This turns out to be an illusion that reflects our own desire — or, perhaps, just the filmmaker’s desire — for a cookie-cutter version of history, one in which an increase in free speech and civil rights leads inevitably to the fall of dictatorship. The Helsinki Effect does nothing to challenge this simplistic narrative, nor does it reflect on its use of AI in an interesting way. We’re left with a documentary that fetishizes the archive for its own sake only to tell a story that has long ago grown stale.

Leave a Comment