Soviet Animations from the Mezhrabpom studio

J. Scheljabuschski’s Katok (1927), M. Benderskaja’s Prikljutschenija kitajtschat (1928), N. Chodatajew’s Budem sorki (1927), L. Amalrik and I. Iwanow-Wano’s Blek end uait (1932)

Vol. 15 (March 2012) by Patricia Bass

Twice during this year’s Berlinale festival, a series of Soviet animations were projected as part of the The Red Dream Factory Retrospective. Mostly silent with Russian intertitles, accompanied by the pianist Maud Nelissen (also known for her accompaniment at the Telluride Film Festival and the Pordenone Silent Film Festival in Italy), these are not films with a big audience. Nor are they easy to find: according to the head of the Russian Film Archive who introduced the work, at least 80 percent of silent films have vanished due to what he termed “a consumerist approach to film”.

Such a phrase is a becoming introduction to these films which were, and continue to be, highly imbued with an “anti-consumerist” tone. Stalin is said to have ordered “Disney-style” animated films to be made in the Soviet Union (an “invisible order” of which there is no documented proof), but the films projected at the Berlinale seemed like anything but a cog in the American cultural hegemony.

Ice Rink

The most famous of these films may be Ice Rink (sometimes translated as On the Skating Rink) by Juri Scheljabuschski (1927). “One day in the deepest winter”, it begins via Russian intertitles, “our little hero went for a meander…”

Our little hero is a diminutive stick figure, whose cursory representation shows only a line for a body, arms, boots and a winter hat. The story follows our hero as he tries to go ice skating. Like any film, desire encounters obstacle, and a story is born: the hero spies on a stick-figure woman who is ice-skating with a grace surprising for elementary animation. The simplicity of her form and movements creates an aesthetic impossible in live-action or even contemporary animation cinema as we know it. Our hero’s obstacle: lack of funds. With empty pockets, he tries to scale the wall, and encounters not only the Forces of Security (an overweight guard), but also the Forces of Hierarchy (an overweight man who, having paid his ticket, had first dibs on the ice rink and the image of femininity).

Although lacking in both financial and corporeal opulence, our hero has an important asset: ingenuity. He scales the wall, creates a single skate for himself, and provokes a slap-stick physical comedy the moment he enters the ice-rink to the “public eye”.

Light as the animation may be, it introduces tropes that the following Berlinale animations show to be characteristic of Soviet animated film: the natural oppression of the capitalist system, the comic opulence of the dominating class, and the triumph of the underdog.

Adventures of the Little Chinese

Take, for example, the much more politicized Adventures of the Little Chinese made only one year later.

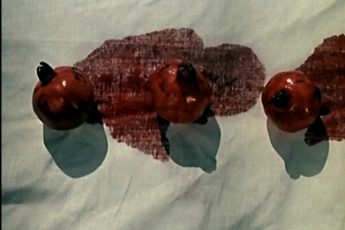

The film is a puppet stop-motion animation, a realm of Soviet filmmaking that was born with the innovative work of Laidslas Starevich – a stop-motion animator of embalmed insects in the 1910s who was subsequently decorated by the Tsar. Starevich launched the concept of mixing live-action and stop motion with his 1913 The Night Before Christmas, and much Soviet film, like Adventures of the little Chinese, montaged accordingly.

Two young Chinese children are oppressed under the system of colonial rule, and, predictably, adventures soon follow. Given that the children have features reminiscent of racist Western stereotypes and goggly inward-slanted eyes, it is no surprise that “Tom” – the Englishman, symbol of the West – is a morbidly obese man with pasty cheeks that hang over his collar. The intertitles inform us that “Tom was becoming fat while the Chinese were going hungry”, a possible reference to the economic difficulties of the Soviet Union in comparison to the capitalist powers of the West.

Early in the film, we learn that “our little Chinese are made to work as Tom’s kitchen servants”. The conditions are less than ideal: the young girl cries from over-work, and Tom beats both of them with a frying pan that is half the size of his bloated head. The boy comforts his sister, “Don’t worry Lika, there is a country in this world where the poor are free, and the children are never beaten”. Thus the tale begins.

The “little Chinese” are chased by a live-action tiger and float in a matchbox over a stop-motion sea to find their utopia. They hit land, and find indigenous black inhabitants carrying a white man on a raised chair: not the ideal they were looking for. After the children play with the equally stereotypically-featured children living in this strange land, the narrative panel reads that the “coolies” must continue their search for utopia.

Next, our protagonists land in the United States of America. Amid looming buildings and bustling capitalists, they catch a glimpse of the Statue of Liberty: “This is the Statue of Liberty. She tells all the nations of the world that America is free and glorious”. But is it? A bustling capitalist is quick to inform them that “colored people aren’t wanted here! Go home, Bolshevik trash!”.

The children were never before identified as Bolsheviks, and their physical representation – what we today would call a highly racist depiction – raises a myriad of questions about the possibility of mobilizing problematic tropes to situate racism outside of the Soviet Union, and the equally mysterious identification of oppressed peoples as “unconscient Bolsheviks”.

However, the film doesn’t dwell on this: in several seconds, the protagonists have found a blimp that carries them off to a land where a very-white child army is doing exercises on a hill: the Soviet Union, a true children’s utopia!

Let’s Be Attentive

The organizational forces behind the Berlinale’s retrospective were careful to add examples of non-fiction Soviet propaganda animations as well. Given the explicit pro-Soviet vibe of the previous “fictional” films, however, they don’t differ greatly. In Let’s Be Attentive, the same characters presented in Skating Rink and Adventures reappear, as if for another episode of the same show: this animated explanation of international politics represents Great Britain via a map on top of which a fat, cigar-smoking, googly-eyed fat man squats. “We’ll crush the Soviet Union with our embargo!” yells the corpulent antagonist, as animated maps show trade routes (a series of moving arrows) being blocked by Great Britain.

This film is a plea for help. Real footage of Soviet workers buying government bonds is interspersed with animated suggestions by the filmmakers to do the same: “We fought the bourgeoisie with guns, now we fight them with roubles!”. By buying government bonds, Soviet workers re-animate the series of moving arrows: industry has reignited in the Soviet Union, and the economy is saved: internal trade replaces international trade! Soviet utopia is once again restored.

Black and White

Government propaganda and a thin-fat dominated-dominating black-white schema is once again married to exceptional animation work in the film Black and White: a political statement on the colonial situation in 1932.

The film opens in the setting of a colonial village in Africa: a white slave-master whips a group of identical slaves, and a chain gang of black men languish behind bars. The only free person of color is the priest, and we are tipped off to his corruption by the fact that he, too, is morbidly obese. Indeed, he doesn’t only share the visible and biological signs (whiteness, corpulence) that Soviet animators seem to link to corruption and greed, but takes part actively in the oppression machinery. Notably, the viewer is witness to the white man paying him off (in pineapples, no less) so that he will preach to the indigenous population the value of colonial servitude. The viewer is also witness to revolt: “If you like your coffee with sugar”, one slave asks a “sugar king”, “why don’t you make the sugar yourself?”. The slave is imprisoned immediately.

After a series of powerful images of oppression via artfully done black and white animation, the directors leave us with a simple message: “Poor negro, how was he to know that such questions must be addressed to the Comintern in Moscow?”

This naïvité sums up the complexity of race and politics that all of these filmmakers seem to struggle to express with limited means. If capitalism = fat = white = bad, then why have all the oppressed peoples (who are defined, by default, as anti-capitalist = thin = of color = good) not joined the brotherhood of the Soviet Union? Could the world possibly be more complex than a 12-minute film with no shades of gray?

Leave a Comment