In 2015 and 2016, the working conditions of interns at the Berlinale made it up to the German Bundestag. In these two years, the Berlinale had “employed” 115 and 133 interns respectively, whereas in the six previous years, it was only a little over thirty per year. The steep rise in internships made some believe that the festival was trying to circumvent German labor laws. In previous years, the majority of the auxiliary workforce of the festival (between 130-170 per year) had been employed under minijob contracts, which enforce a hourly minimum wage and add up to a monthly salary of under 450,- Euros, exempting them from the income tax (the low-payed minijobs are intended as an additional income beside one’s main earnings). There is, however, no minimum wage for internships. Since the Berlinale gets funding from the Federal Government of Germany, some newspapers picked this up as a story of government-sanctioned exploitation. The Bundestag justified their position by saying that the Berlinale interns get paid roughly the same amount as the minijobbers. That a working contract as an intern at the Berlinale asked for 39 hours per week, which makes an hourly pay of 2,88,- Euros, or, about a quarter of the amount set by the minimum wage legislation, did not keep either side from closing the case. Meanwhile the Berlinale director, Dieter Kosslick, earned a yearly income of 294.412,82 Euros in 2015, the difference between the two salaries equal to the development of the manager-to-worker pay ratio, which was around 1:60 in 2015.

For most festivals in most countries including Germany it is, of course, routine to hire volunteers, which don’t get paid at all. Whether festivals use free labor or the working poor may not make that big of a difference. In either case, the hiring discourse is often based on the additional “benefits” the job supposedly offers, such as a free festival pass, access to reserved areas or parties, the promise of networking or opportunities to converse with important cultural actors, and so on. The real justification for the low paid labor, then, is the hope of belonging. With a reserve army of aspiring cultural actors waiting for an internship to “get in” , the lucky few that do are encouraged to interpret their precarious contracts as an invitation to be part of the “highly professional and artistic cultural industry”, to use the words of the Bundestag.

As the Berlinale kicks off this week with an exclusive online event for professionals (for which we too are accredited), the distance between those who belong and those who don’t has been made acutely visible. None of the selected films are available to the wider public, there are no after-hours events, festival galas or free lunches and, most importantly, no screening rooms accessible to those lucky enough to get a ticket that could blur the lines between insiders and outsiders. (The fact that the Berlinale is planning to stage a separate event for the wider public in summer only accentuates this division.) Hopeful volunteers, interns, minijobbers, trainees, and contractor employees are now kept at bay by what looks like a self-isolated bubble, in which selected filmmakers, producers and distributors claim possession over cultural resources and experience. Once hailed as the biggest public festival, today’s Berlinale is thus everything but popular. Indeed, only an established cultural elite would so easily dispose not only of the lower- and mid-level workforce, but also of its large semi-professional audience, both of which were hitherto willing to seek social integration, or the illusion of it, through the precarious labor market. Where cultural capitalism succeeded in assisting these hopeful outsiders with an optimistic outlook, the blatant aristocratic structure of the festival has, alas, opened the door for pessimism. Whether the admittance of these inequalities will now lead to increasing secession, inspiring talents at the fringes of the cloistered cultural production processes to take matters into their own hands, remains to be seen. But the lack of a labor market capable of sustaining a neo-Protestant work ethic in which hoping and dreaming are made obligatory, may, after all, leave some room for change.

***

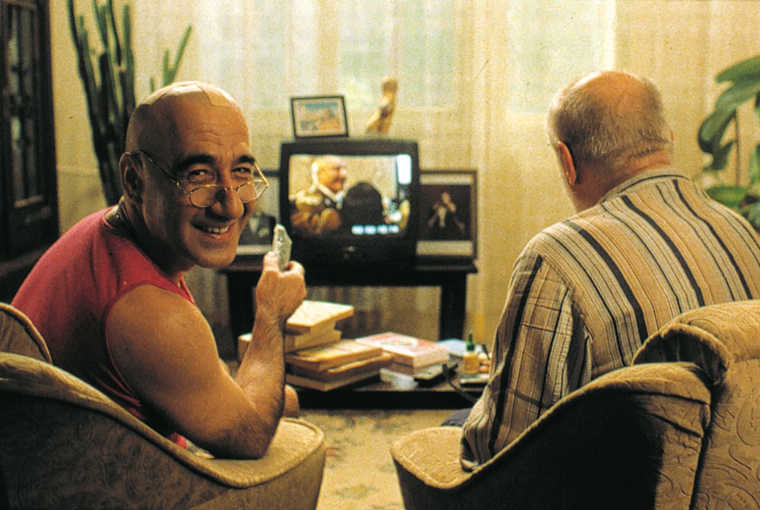

In this month’s issue, we bring you two pieces related to our 2021 focus on Romanian cinema. Anastasia Eleftheriou examines the role of montage in Radu Jude’s Exit of the Trains, which asks how we can document and remember the atrocities of the Iași pogroms. And Lucian Tion argues that the failure of Niki and Flo prefigures the successes of the Romanian New Wave.

Our February issue also features three reviews from the Rotterdam film festival. Daniil Lebedev reviewed Dea Kulumbegashvili’s Beginning, a sad tale of biblical dimensions. Jack Page discusses Looking for Venera, Norika Sefa’s impressive take on femininity, coming-of-age stories and town life. And Melina Tzamtzi saw Marta Popidova’s Landscapes of Resistance, which documents the story of a female ex-partisan who fought against the Nazis. Finally and in addition, Jack Page also saw Elvin Adigozel’s latest film Bilesuvar, which paints a piecemeal portrait of the mundane.

We hope you enjoy our reads.

Konstanty Kuzma & Moritz Pfeifer

Editors

Leave a Comment