We met Stanislav Dorochenkov at the FID film festival in Marseille (July 19-25), where he presented his experimental biopic on avant-garde figure Ilia Zdanevich. Dorochenkov speaks about the motivation behind making “ILIAZD”, its artistic premise, and Zdanevich’s views on art and the Russian revolution.

Your film focuses on a character of the avant-garde who is hardly known in France: Ilia Zdanevich. What led you to make this offbeat portrait?

Ilia Zdanevich is an unusual figure, and the project goes along with his character by developing an offbeat idea, the time code and the intervals of the film being out of sync… Ilia Zdanevich was born in Georgia and became a Futurist – an artistic movement in Russia that sympathized with the idea of sparking a revolution in the 1910s and 1920s. This movement, which is related to Dadaism, seeks to provoke things, to test things. Fittingly, Iliazd developed and changed his ideas throughout his life.

With the help of Futurism, Iliazd developed the movement of “vsiotchestvo” along with his friend Michel Le Dentu, which was translated into French by Régis Gayraud, an Iliazd specialist who served as both actor and scientific consultant in the film, as “toutisme” [“everythingism”]. He finds inspiration for the contemporary world in very ancient, primitive forms, in a time when man was anonymous and prehistoric and drew on the walls of caves. He draws a moving line between that time and today. Rather than reading the fashionable poets, he is interested in something very distant and forgotten. Charles Peguy said that revolution is putting in place the things of the forgotten past. And Walter Benajmin speaks of the “tiger’s leap into the past”. We cannot answer the question who Iliazd is. The film is a search for Iliazd’s identity. The mystery of Iliazd’s identity haunted me for a long time in this film, and the film answers this question in a way. He might be a sort of Ulysses of the 20th century. He also embodies a “way of life, a way of living” which is completely opposed to our way of living during the Covid-19 pandemic.

This multifaceted aspect is really apparent in your film as it’s a film that borrows from different media: sound, theater, performance, poetry, illustration, and typography. Was this protean aspect meant to evoke the multiple identities of Ilia Zdanevich?

The notion of multi-dimensionality was very apparent from the start. Nevertheless, the protean form had to find a specific form to manifest itself in the film. Otherwise, one gets lost, as one would in a labyrinth, so I first had to compose a thread and with it a way out. About Iliazd, Regis Gayraud has said that “to dive into him is a journey”. I plunged into his life and the question was how do I return from it. The question of return, the Greek question of Ulysses, is central to the film. Iliazd was exiled without being exiled, he came to France to study and stayed, but he had a complex relationship with this country which treats many foreigners badly. Legally speaking, Iliazd was a stateless person. A Norwegian philanthropist called Nansen (High Commissioner of the League of Nations for Refugees) set up the Nansen passport for people who had been expelled from their country, a document which Iliazd had acquired. Once the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917, there was no nationality available to him. He was a man of the world, stateless, which was a 20th century status. I don’t know if you can still find people who have the Nansen passport as a recognized status today.

Ossip Mandelstam addresses this theme in ‘Journey to Armenia’, which is a kind of poetic exercise of displacement and of choosing another homeland (in Mandelstam’s case Armenia) in order to lose one’s identity and in a way find it again – like Ulysses does in the Odyssey. In the film we travel a lot: to Marseille, to Tbilisi, to Paris, and we can find this ‘Odyssey’ idea reoccurring there too.

Regarding Mandelstam, it’s funny because I made my first film Life falls down as a menagerie based on Mandelstam’s poems. I was always pursuing this idea of engaging with an author who interests me. Of course, I don’t work on the authors that interest me but rather I work with them.

What was the creative process like? Did you have a script or fragments of a script in advance of filming?

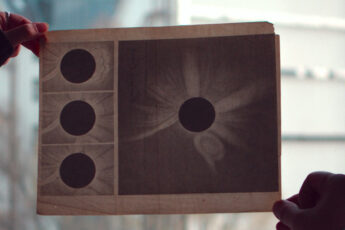

Iliazd is a labyrinthic journey, the idea for the script didn’t come to me right away, it was built up in chapters. In the text I wrote on my film, I talk about Iliazd’s multiple identity: he was an editor of rare books, an inventor of a new language, an ethnologist, a byzantologist, a costume designer, a fabric designer, a researcher of ancient architecture, a writer, an organizer of dada balls, an excellent photographer etc. This gives us a challenging multiplicity to work with – uniting all these aspects that seem so disparate is not easy, which is where the idea of labor comes in. The scenes of engraving work – of etching – were a guiding thread in the film. It’s an ancient crafting ritual to create a book. I wanted to put in place this notion, the construction of something, specifically a book that is made, and to raise the question what it is like to work, how much time it takes to work on something. Over the course of the film, the film regains a certain rhythm which leads to the disappearance of Iliazd. In the end, Iliazd dies standing with his cup of tea in the kitchen on December 24th.

You say that Dadaism began in Tbilisi, Georgia. You also mention the life of primitive painter Pirosmani. Obviously, this brings to mind various films about Pirosmani, for instance Shengelaia’s Pirosmani and Sergei Paradjanov’s Arabesques on the Theme of Pirosmani. What vision of Pirosmani did you want to convey?

I really liked Shengelaia’s film. Pirosmani’s part is played by this magnificent painter Avtandil Varazi, as if it were necessary to be a painter in order to play a painter! But in fact, I wanted to concentrate on a specific passage about Pirosmani from Iliazd’s book. In his book, Iliazd makes this discovery of the genius that we don’t know, a genius who appears out of the blue and who would become a national painter a few decades later. Though he evokes this in a very simple and humble way, Iliazd discovered Pirosmani and materialized him somehow.

Generally speaking, all kinds of vision of Georgian cinema were very present, Paradjanov of course. But I didn’t have anything particular in mind. I was thinking more about Iliazd’s Zaum plays than about cinema.

How did Iliazd feel about the revolution?

1917 marks a very important date for anyone who experienced the Russian Empire. The world was changing. Iliazd was a law student in St. Petersburg at the time. Being a Futurist, he was rather optimistic about the revolution. But he ultimately became tired of the revolution, stating that “I leave the revolution for architecture”. In the film we witness this gesture as he joins an expedition in the Caucasus in the historical region of Tao-Klarjeti. At the time, a war was being waged between Russia and Turkey, which ends in the region being taken over by the Russian army. The Ottoman empire collapses. The quest of the expedition was to discover the remains of ancient Georgia. Iliazd identified and mapped the architectural plans of ancient churches dating from the 5th to the 11th century, which are scattered all over this region. After the expedition, Iliazd left for Tbilisi, arriving in the short period when Georgia was independent before the Bolsheviks took over.

In this period, Tblissi becomes a focal point of Russian artists’ exodus. Many people of the avant-garde end up in Tblissi. Iliazd stages various performances, writes his Zaum plays, and founds his 41° book edition. A very old idea of his is to study art in Paris, and so in 1921 he leaves a still-independent Georgia for Paris via Istanbul, never to return to Russia. He had very funny ideas about Russia, as he played around with a peculiar and provocative notion of “Russophobia”. He advocates the idea of recomposing Russia into many states.

Iliazd is a separate entity. Naturally he finds himself doing things that are surprisingly different from what others do. He doesn’t get stuck in the revolution or in Futurism. The revolution is disappointing as it backfires, turning on those who helped materialize it in the first place.

What was the process of working with the archive like?

I set out to make a more documentary film but, studying the archive, I discovered that it is not only an archive, but also a proposal for a stage production. A hypertheatrical “ball” – that is a multi-disciplinary event that combines elements of dance, music, performance, cinema, and theater. Iliazd accumulated everything, he didn’t throw away his papers, his archives in the Rue Mazarine became a place of pilgrimage where true treasures can be found. At some point, the archive was moved to Marseille. Regis Gayraud catalogued everything that was unpublished and that had not been studied yet.

Iliazd pioneered a certain way of speaking about heritage. And by studying ancient Georgian architecture, he became a Byzantologist. Iliazd went to Catalonia by foot and wrote a journal on a city in Catalonia that I have deciphered and excerpts of which I inserted in the sequence where he talks about the nostalgia he has for Georgia towards the end of the film. All these writings have guided me.

You are currently developing a new project centered around Ulysses. Can you tell us about it?

So ILIAZD is also related to the Iliad, and with this new project I am currently working on, I’m asking myself the question what Homer was doing between the end of the Iliad and the beginning of the Odyssey. It will be a film about the passage between both, about Homer’s research between the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Thank you for the interview.

Leave a Comment