“To Dive Into Ilia Zdanevich Is a Journey.”

Stanislav Dorochenkov’s ILIAZD (2021)

Vol. 118 (October 2021) by Anna Doyle

One of the first avant-garde films to have ever been made is supposed to be Vladimir Kasyanov’s 1914 Drama in the Futurist’s Cabaret N°13. Now lost, the list of figures who participated in it includes David Burliuk, Mikhail Larianov, Natalia Goncharova, Vladimir Maïakovski and perhaps Ilia Zdanevich. It opened with a sequence of cabaret artists painting their faces in preparation for the evening show. As the preparation work behind a performance is shown, the film breaks the wall between the spectator and the actors. The birth of avant-garde cinema is therefore inherently linked to a vision of cinema as being at once an act, a performance, and a way of life, thereby crossing the boundary between art and life. This vision of cinema as a performance, as a ball or a cabaret, between poetry and art, between sound, costume, and theatrical effects, finds a contemporary iteration in Stanislav Dorochenkov’s debut feature ILIAZD. In this protean film, we enter the world of the Russian avant-garde through an offbeat portrait of Russian futurist Ilia Zdanevich.

If the film was first set out to be inspired by archive material related to Ilia Zdanevich’s life, it soon became what Ilia Zdanevich might have hoped it to be: an experimental film that borrows from different media, being sonic, theatrical, performative, poetic, illustrated, and typographic at once. Since Ilia Zdanevich was himself a polymath, this protean aspect reflects his multiple identities. Also known as “Iliazd”, he was a Georgian-born futurist who never stuck with one artistic movement or profession. If editing books was his main profession, he was also a poet, a playwright, a photographer, a geographer, a geometrician, an astrologist, a philologist, an ethnologist, a fabric designer for Chanel, as well as a discoverer of forgotten talents – notably of that of Georgian painter Niko Pirosmani, astronomer Guillaume Tempel, or the medieval poet Comte de Cramail.

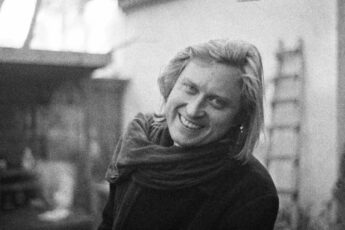

The film is also a portrait of the film’s director Dorochenkov himself. It starts with Dorochenkov’s voice stating that “Iliazd was an inalienable part of my life”, and adding that his (that is Dorochenkov’s) life would stop without him. Dorochenkov plays the role of “Ilia” in the film. Dressed in a strange buffoon costume for most of the time, he quests for his identity. The character of Ilia is like the ghost or double of Zdanevich who is in direct contact with the spirit of Ilia Zdanevich without truly embodying him. To make films with – rather than about – great literary figures is a project Dorochenkov has pursued with different films. He has worked with poetry, for instance with Ossip Mandelstam in La vie est tombée comme une menagerie and with Shakespeare’s sonnets in Ateisti Fuminati. His film Postface a la brochure de 1942 was inspired by Russian Slavicist and so-called “guardian of national culture” D.S. Likhachov. Furthermore, he has made a project around Bruno Schulz, focusing on his lost novel and drawings that together made up Le travail de Messie. And now, he has turned to polymath Ilia Zdanevich.

The film rejects the classical visions of the biopic and of historical reconstruction in cinema. An intertitle towards the end of the film positions it “against the ugliness of historical reconstruction”1, as if the film were a manifest, a provocation, and a meta-poetic reflection on the way it’s made. The spectator encounters a full-fledged poetic experience of Ilia Zdanevich’s life from birth to death, with all the passions, desires, and wanderings that project encompasses. Furthermore, it is hard to tell between truth and fiction in the life of a man who played with the mistakes of his own identity. If the film shows true facts, for example the fact that Ilia Zdanevich died with a cup in his hand, the spectator does not know whether other parts of what is being retold are true: is it true that he fell in love with a seven-year-old whom he supposedly wanted to marry? Or that his mother raised him as a girl in his early childhood? It is an apocryphal vision of a life in movement, where facts are rejected in favor of a phantasmagorical and imaginary life, where identity is not static and objectivity is not relevant. This is also because some of the drafts in the archives of Ilia Zdanevich were themselves apocryphal. We dive into the life of Ilia Zdanevich as we would into his books, which is quoted at length throughout the film. “To dive into Ilia Zdanevich is a journey,” Dorochenkov quotes Régis Gayraud as saying. Indeed, perhaps more than anything, Ilia Zdanevich is the embodiment of a way of life.

The film is also a voyage encompassing Marseille, Berlin, Constantinople, Tiflis, and Paris. It is a labyrinthic quest for identity. Ilia is a Ulysses of sorts, haunted as he is by a sickening nostalgia, the fate of those who are in constant search for their identity – the exiled living overseas who are never to return. Ilia Zdanevich lived in many cities and was indeed stateless. After the fall of the Russian Empire in 1917, he obtained a so-called Nansen passport – a stateless person’s identity document – and would never return home. He did not revert to patriotism, calling the Russian empire “a house of shit”, and fled to Istanbul on his way to Paris. In a way, one could say he was following the steps of the intellectuals forcefully transported on the famous “philosopher’s ship” in 1922, who were expelled from Odessa to Istanbul. During their trip, the exiled (ex-)citizens of the Soviet Union debated whether they should hoist the orthodox flag or the red star on the Hagia-Sophia – an episode documented by Dorochenkov. Such gestures of non-conformity and exile are omnipresent in the film. Dorochenkov’s Ilia walks the streets of Marseille in a costume; eyes glare at him as he squashes a tomato with his bare hands. He epitomizes the role of the foreigner, of a stranger who is not at home anywhere, of a citizen of the world, a “foreigner […] among the foreigners”. At the same time, the voice-over features passages from Vladimir Jankelevitch’s Irreversibilty of Nostalgia. The text evokes nostalgia as being the fate of the exiled, of those who are neither here nor there, who live a double life as citizens of an ‘invisible republic’. After desiring to run away, he is finally overcome with nostalgia for Georgia.

This position of exile and statelessness corresponds with a universal language. In several parts of the film, we hear Zaum, an experimental language creation invented by Ilia Zdanevich along with his friends Velimir Khlebnikov and Aleksei Kruchenykh. In Zaum, all accents are welcome. In his play called Janko, Ilia Zdanevich had already made different people with various cultural and linguistic backgrounds speak this sound-language with different accents – one character has a German accent, two Albanians recite the alphabet, another speaks with a click in the tongue, another one uses only one vowel. In the film, people from all over the world speak Zaum in their own way too.2 The different characters speaking Zaum wear different make-up and costumes, as if they were part of a Dadaist ball and their farcical ways of being, despite their internal differences, were interchangeable.

Russian futurism is different from its more well-known Italian version. Italian futurism is drawn to a new world, an urban and industrial world that is articulated by the language of machines and crowds and which rejects moral values in favor of raw energy. Roman Jakobson claims that Russian futurism does not long for this new industrial world in the same way, but rather experiments with new forms of autonomy in language.3 Russian futurists considered language in its physical reality – acoustic and articulatory -, without using it to express meaning. Zaum illustrates the uselessness of an art that appears to have no meaning, but that has become, for Iliazd, the most important part of his life. For Jakobson, Zaum reveals the function of poetry itself when it is purged from communication and prose: “the focus put on the message for its own sake is what characterizes the language function of poetry.”4 Zaum is a transmental language whereby language is reduced to its sound and graphic material. In the same way, Dorochenkov’s film uses Zaum typography for the subtitles and intertitles. This typography is like a double reading of words capable of transmitting an emotional expression that is lost after mechanical printing. Sometimes, it seems that the spectators were turning the pages of a book as the film progresses, calling to mind Zdanevich’s own illustrated books.

Occasionally, the film makes mistakes or creates moments of doubt: error replaces rules while visual and sonic effects disturb the naturalist aspect of cinema. The film is polytextual, polymorphic and polyphonic. It is black-and-white at times but for the most part colorful, and we hear different sounds and different textures of voices. Not only a radio announcer speaks in Zaum; there are dialogues between theater actors and commentaries of Dorochenkov which are sometimes superimposed to the point that we cannot make any sense of them. The futurist philosophy of life is one of testing, provocation, and of farce, and this constant surprise is found in the film. It is said in the film that one should never start a sentence with “art should”, and that talent is not necessary to make art. That is because it is not language and art that are the ultimate material of this poetry for the futurists, but the poet himself.

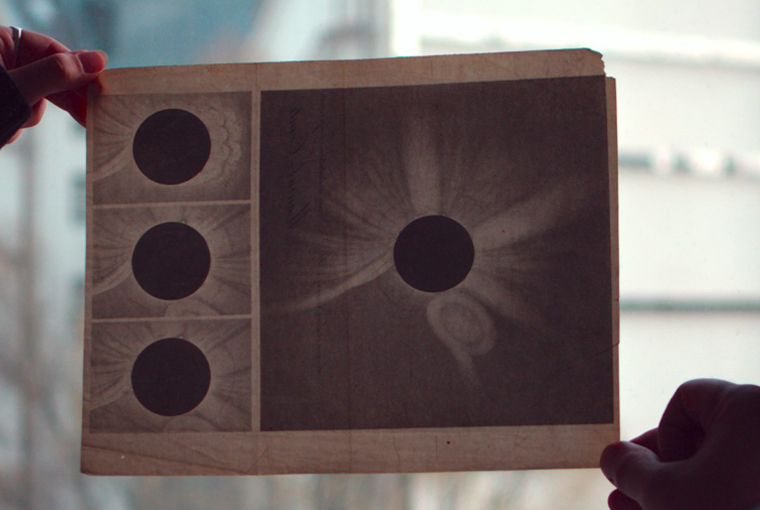

In contrast to the Italian futurists’ quest for a superior modernity and their skepticism of tradition, longing for the past is fundamental to Ilia Zdanevich. Zaum is not only about the new world. It is also a return to the origins of language, which in Russia was the panslavic language. Secondly, in the film we travel through caves (as in Iliazd’s novel Rapture, in which the characters hide in a cave), drawing us to periods before humanity had divided itself into modern nations. This brings to the fore what Ilia Zdanevich called “vsiotchestvo“, “everythingism”, a movement coming out of futurism that consists in finding forms in the ancient past to inspire the art of the present, say a prehistorical cave drawing, which appears to be more relevant than a fashionable poet when it comes to revealing the potential of a new poetry. If for many Communists, the art of the past was condemned for being bourgeois, for Ilia Zdanevich, it is a discovery. In the film, we follow his expedition to Georgia for example, during which Zdanevich sought out the medieval churches of the 9th to 11th century. Zdanevich maps and identifies “Asteroidal edifices”, churches built in the shape of stars. This initial interest will later trigger a passion for Byzantine art. The film shows these architectural blueprints like archives that look more like avant-garde drawings than maps. Another discovery in Georgia is the talent of primitive painter Niko Pirosmani. This painter of taverns, condemned to a life of alcoholism and poverty, was to Zdanevich an equal to Giotto or Picasso. Here, the film recalls other cinematographic works made about Pirosmani: Shengelaia’s Pirosmani and Paradjaonv’s Arabesques on the Theme of Pirosmani. Paradjanov’s work is also a reinvention of biographical films on artists that elude historical reconstruction. Rather, it draws parallels between cinematography and painting, like when Pirosmani enters the frame and approaches modernday Tbilisi with his muse and in the company of Saint Georges. In Zdanevich’s work on the other hand, the actor impersonating Pirosmani does not resemble him at all, his face being blurred, anonymized and transposed to our modern days, as if to say: Pirosmani is here with us today and can be each and every one of us.

Trying to orientate themselves in the labyrinth of ILIAZD, spectators feel like a contemporary Theseus following Ariadne’s string. Although multidimensional, the film stops at times to dwell on beautiful images of etching. The repetitive work of etching is the calm moment where the film rests. The film suggests that the poet’s destiny is to be forgotten, yet we remember Iliazd through his books, which remain with us till today. The presence of this preparatory work, etching, shows that the film is really its own creative process: a film searching for its own form and identity, reflecting on itself as an artwork and trying to reach the limits of a total artwork.

References

- 1.Translation by author.

- 2.Regis Gayraud, Poésie et prose d’un Zaumnik : Il´ja Zdanevič. Quelques caractéristiques communes, Revue des Études Slaves, 1995 67 (4); pp. 563-575.

- 3.Roman Jakobson, Fragments de La nouvelle poésie russe in Huit questions de poétique, Seuil, 1977; p.15.

- 4.R. Jakobson, Les six fonctions du langage et la fonction poétique en particulier , extrait de Essais de linguistique générale, 1960; p. 356.

Leave a Comment