We interviewed Aleksandra Sekulić, who works as a curator at the Center for Cultural Decontamination in Belgrade (CZKD), about the film program she curated together with Branka Benčić on women amateur films at the AVANT 2022 festival in Karlstad/Kristinehamn (23-24 September). Sekulić explains how she became interested in experimental and amateur films, what the different connotations of “amateurism” are, and how they relate to feminism in the (post-)Yugoslav context.

Could you please tell us more about how your work with experimental film archives and curating amateur films started?

I started producing films and working on films more broadly in the 90s during the Yugoslav wars. At the time, there was a Low-Fi Video movement that was part of our alternative culture in Serbia. This movement was open for all kinds of experiments, from famous artists to amateurs or filmmakers from distant villages, everyone could come and show whatever they wanted to. The movement was inspired and established by three of my friends who were inspired by an older generation of famous filmmakers, prominent teachers and lecturers on cine-amateurism and avant-garde film. The aim was to use the democratic ability of VHS cameras to continue the emancipation from conventions in film and moving image production that started in local cine-clubs in Socialist Yugoslavia. It was part of the wave of microcinema in 90s that was pushed forward by international networks in spaces that were emancipating from the usual film club structure and cinema experience. This resource, which involved community and broader audiences, is today known as “radical amateurism”, as it stepped outside of academic, gallery or conventional cultures to develop emancipated forms that react to and impact the conventional culture of films.

How is so-called film amateurism in Yugoslavia different to that in other places of the world?

“Amateurism” in Yugoslavia does not mean the same as it does in other countries, where the field of amateurism often means dilettantism. Amateurism, with its infrastructure of cine-clubs, was the playing field for the most experimental forms of avant-garde production in Yugoslavia. Apart from loving films, amateurs in the structures of cine-clubs in Yugoslavia had to pass exams and acquire certain skills to be able to make their films. At cine-clubs, members, associates, and visitors would debate, discuss, and screen films, thus helping develop cinema culture. They enabled educational measures as well as facilitating the production and dissemination of films, and thus helped establish an engaging film infrastructure.

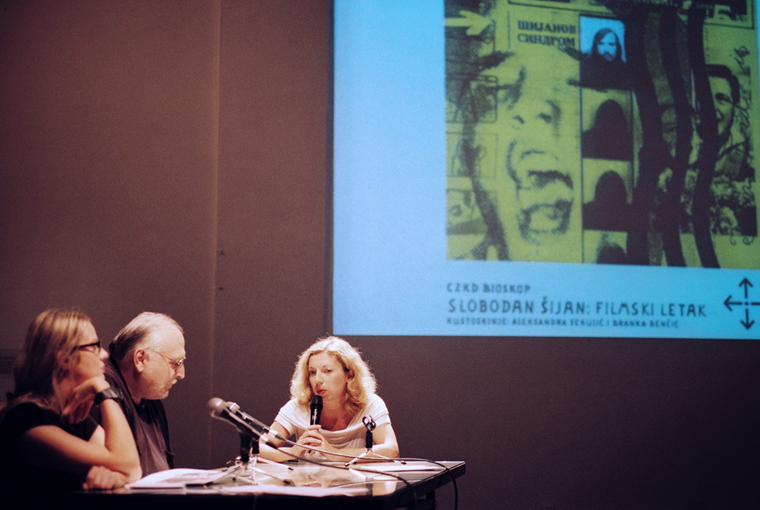

On the fringes of Pula’s famous film festival, amateurs established their alternative festival in the 1970s, the MAFAF – also known as „Little Pula“ –, which would take place a few days before the official festival and helped establish a complex net of cooperation between cine-clubs in different Yugoslav cities: Pula, Split, Belgrade, Zagreb, Ljubljana, Pančevo, and others. My collaborator Branka Benčić’s exhibition in Pula on the “Invisible History of MAFAF” was a starting point for our work, as we made it into an extended exhibition entitled „A Look From Belgrade“ at the Center for Cultural Decontamination in Belgrade in 2011. Since then, we have worked on these complex histories and common cultural spaces in Yugoslavia, despite facing major obstacles as the influences and networks of cooperation are very hard to entangle. Our next project was an exhibition of the 1970s lo-fi fanzine Film Leaflets by Slobodan Šijan, which we first showcased in Pula and Belgrade in 2012 and which are now on display here at AVANT, curated by Dejan Sretenović. The Film Leaflets were distributed in front of the Pula film school by Šijan himself. Then we prepared the “VIDEO TELEVISION ANTICIPATION” exhibition. It ran in the Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade and Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb in 2013 and showcased art works as well as retracing the history of movements, groups, and collectives from the 90s. These films and videos were thinking about how they anticipated and imagined the future, and specifically how video and television influenced each other. One of the works shown there and at Avant is Sanja Iveković’s Personal Cuts, which thinks of the infrastructure of television as the dominant media system.

What made you start working on women amateur films specifically?

This program was our attempt to catch up because women authors from the period of Yugoslav cine-clubs were not visible in our generation, they were not canonized in a way that we could consider them a cultural resource. We arrived at a situation where many of my colleagues tried to digitize the works of these women who should also be considered as subjects of research and in order to catch up, we put a focus on their work. And we are not only portraying cine-club authors, but dynamic fields of different experimentation in the media from the 60s through to the 80s, when experiments in video and film were influencing each other. Film expanded with the newly discovered medium of video. A lot of films were rediscovered, like Erna Banovac’s Erna. The film was shown in several retrospectives, but it was never considered as a finished film by Erna herself, which may be one of the reasons it ended up in the archive. One of her colleagues from the the cine-club period, Miroslav Petrović, met with her and offered her help in finishing the film in 2010. Erna passed away in 2020, and now we have two versions of the film circulating.

We are also showing cine-club works by Dunja Ivanišević and Tatjana Ivančić. There is an interesting story about Dunja’s film Žemsko (“Gal”), whose title translates as “female”. Along with her colleagues, she would go to cinema clubs and get some film to shoot. Once, they were supposed to send their film to an amateur festival in another city in Yugoslavia in 1968. Somehow, although she had handed over her film to her colleagues for them to hand it in, the male colleagues didn’t send her film to the festival, while all the remaining films by male authors where successfully submitted. This discouraged her and so she never made films again. This is her first and only film, as she went on to become a teacher. Now, many consider it to be the first feminist film in Yugoslavia. Dunja explained that she would not call her film a feminist film, but that it is simply her reflection on the ideas of the time.

So how about feminism, did these women self-identify as feminists? Or as part of a wider emancipating movement? And what did this mean to them in terms of filmmaking?

Sanja Iveković and her works strongly affected feminism in our region, as well as other aspects of social thought related to emancipatory ideas. Iveković might have been the most radical figure in her position, openly questioning the media environment despite the repercussions she faced. Some of the women whose works we discovered were actively marginalized despite deserving to be put in the spotlight. Looking back, they are not always part of film history, but should instead be viewed in a wider context of different media shaping them, notably videos that were produced in a specific political and social production context. For example, Bogdanka Poznanovic, a notable figure from the art world, made Heart (1970). She filmed the action of a social movement for which young people are seen moving a big sculpture of a Heart in the streets, thereby experimenting with public space. It was a very important period for art in public space and this is one of the rare documents of this. Divna Jovanovic produced the animation piece Rondo (1964) at Dunav Film school. Looking at it formally, this particular piece is an alternative film. She plays on contrasting political and historical contexts, reflecting on the Rock and Roll generation and the new reality it faced whilst society was enthralled in postwar patriotic culture. The second part of the film with its folk music and the flickering of the film also has a dark and gloomy animation which reflects on Cold War anxiety.

Sanja Iveković often questions the accuracy of media reproduction. Her performances are a very direct experience of the media, which is one of the reasons that they were produced for TV screens. Her awareness of the media landscape made her want to challenge the question of media as a form of single channel media aggression. The film features her with a partially see-through mask over her head onto which she projects short inserts of media coverage, which is seemingly meant as a throw-back to her media exposure. Although reflecting on the media, her films have something intimate about them, they instill courage. She is a female artist experimenting with her own body as well as turning to more social questions.

Tatjana Ivančić made City in the Shop Window (1969), a film of the cityscape reflecting on the windows of the city. It reflects a lot of knowledge of early film experiments with city lights. At the end she inserts a message in the credits where she thanks the window cleaners – a touching gesture of the film. Usually, ninety percent of the cinema apparatus is forgotten in a film as we are invited to only pay attention to the big auteur.

The montage of these women’s films is very striking, as they often contrast two visions: that of the woman as a feminine, leisurely, and free being who dares to deconstruct the male gaze, which is in turn represented by images of virility, of soldiers or politicians on television or even of male fantasies about women in magazines. Would you say that this is a common denominator of these films?

Yes, it is. Take Erna as an example. But remember, even if 1960s counterculture was very strong, Yugoslavia was a socialist country and women had an important role. Women were given the right to vote immediately after WWII. That said, with this emancipation came the burden for women to fulfill several roles at once: they had to be socially engaged, had to work, and they had to be mothers. Many of my colleagues have projects that interview women from ex-Yugoslavia and how they experienced disillusionment or desire in the name of further emancipation.

Thank you for the interview.

Leave a Comment