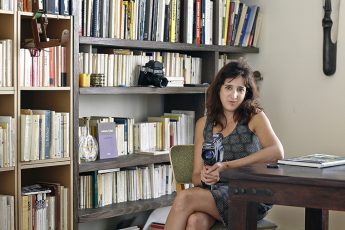

We met with Isa and Donat Qosja at the Thessaloniki International Film Festival (October 31-November 9), where they presented their new film “Three Windows and a Hanging”.

Can you tell us something about the production of this film, knowing that there are extremely few films produced in Kosovo today?

Isa: This is exactly how it is. We produce only one film per year, the budget available is very small, about two hundred thousand. And every year the government gives four-hundred thousand Euros for two films, or for one if it is a long feature. And maybe three or four shorts instead. This is very poor production. In this case, anyone who wants to make a film must wait for a long time, for example I waited for nine years from my last film Kukumi. The production was only from Kosovo, but I got a prize at the Sarajevo Film Festival, which granted me money for the post-production.

What’s the impact of this situation for filmmakers in Kosovo, I mean one can’t film independently under these circumstances?

Isa: That’s true. If we focus on the subject, we are totally independent. But when it comes to the money, we have to wait for it. It is public money, from the Ministry of Culture and the national film center. There is a committee there that gives this money to filmmakers. So, in a way the subject is also influenced because if we decide to do a very specific subject that’s interesting and that costs a lot to do, well this is impossible. So yes, in a way the decision about the subject of the film is not as independent. We must adapt the subjects to the budgets, and this is not easy.

How did you come up with your films’ idea, did you do a documentary or documentary research before?

Yes, it has been fifty years since the end of the war. And all information, which is not and can’t be official, says that we have around 20 000 women that have been raped. During the war. And this is the highest number of all the wars in the Balkans. And no one ever spoke about this, on television. Some women spoke to newspapers or NGOs, maybe three or four years after the incident. Definitely the last few years mostly. I have read stories like this in the newspaper, but it was always without names. People would not show their faces. And this scriptwriter decided to write a script on that – we took these stories and mixed them together in one scenario.

Why did you choose to set the film in a very small village?

Isa: Because it was the reality, most of these stories really took place in small villages. And in villages it is more common that people do not want to speak about it and protect themselves and their pride, it is taboo. The mentality from tradition is strong; they want to keep the story “inside” the walls. For example, Uka, the first man from the village, he wants to keep his authority in the village. And that is true. They want to save their authority in the villages in Kosovo. I think it is the same in Bosnia and Croatia.

Danot: What makes the story unique is that this happened during the Balkan wars, in all regions. What’s specific in Kosovo is that no one spoke about it until maybe the moment the film was out. It has been fifteen years and none of these women, 20 000 women, found a way to speak about it. You have cases in our countries where the men of two villages made a pact not to speak about these stories that took place in their villages. We had to show a way for these stories to come out. And now there are a few initiatives by the government to help women with such an experience, a mall fund I think.

How did people react to the film in Kosovo and also in other Balkan countries?

Isa: I did not expect it really, but the reactions were good. People in the government decided for some reason to help us with the victims now. When we showed the movie in the theaters for two weeks, admission revenues went to organizations that support these women today. I do not know if this will last, we will see. But our film has not reached audiences in small places yet, we have only had our premiere in Pristina. Screenings lasted two weeks and now the film took its way to the festivals. But the first reaction of people in Pristina was good. Also in terms of helping these women, of having the stories come out. But when it comes to the people who have really taken part in this, on both sides, it would be very difficult to say. And there was a case before the movie was finished when someone tried to speak about a rape and was stopped. The problem in the Balkans is actually that even today rape is considered to be a shame. Especially in rural parts. When I was in New York I met a doctor who told me this story. He said that every day a Bosnian woman would go to him with serious health problems. And he said that all women would tell him that their husbands knew about what happened to them but hey would not speak about it for them. They pretend not to know and this is what hurt these women the most. That’s why many women in Kosovo have also hanged themselves.

What’s your future projects and how long do you think is it going to take for you to get funding?

Isa: Some friend in Kosovo told me “it is not necessary to wait another nine years to make a film”. I hope I will not have to wait so long again. I do have a subject: it is a story about a man who crosses the border to another country and marries; there is a village where old people keep in touch with their sons who are not there anymore. Only old people are left behind as all the young immigrated to to the US and Europe. And then there is a sort of black comedy about misunderstanding.

Leave a Comment