We met Jiří Menzel at the Transilvania International Film Festival (May 31-June 9), where he received this year’s Lifetime Achievement award. He dropped a few words on changing perceptions of his films, being part of a cinematic movement, and the risks and merits of freedom.

Have you ever been to Romania with any of your films?

Yes, two years ago I was here and they screened my films.

Since 2001, what critics call a “New Wave” has been going on here in Romania…

I read that there’s great cinema here in Romania, but I didn’t get around watching any of the films yet. To be honest, I don’t watch many films anymore, not even Czech ones. You know how they say: the shoemaker’s wife walks barefoot [Czech proverb]…

But you used to watch a lot of films?

When I was young I saw everything. That’s why I’m not crazy about films anymore: I’ve seen it. I still have some DVDs for entertainment at home, but it’s mostly Laurel & Hardy. That’s what I look forward to seeing anytime.

Do you still watch your own films?

No, absolutely not. Anyway if I’d see the films, it would seem better to me in the spirit than it is on screen. That would bug me, it would remind me of all the mistakes I made when shooting it. Someone said in an interview recently that a filmmaker watches a film either because he’s sorry for the other people because they can’t make films like he can, or because he doesn’t remember how he did it… I think that’s true. That’s two reasons for watching your own films.

You’ve been traveling around the world with your films for many years now. Has something changed in the perception of your work?

I am surprised. I am surprised to see that people still watch my films and appreciate my work, and that the films still make sense today. I like it when people talk about the films because they like films, not because an award or something has to been given away.

I also like traveling around festivals because it’s good for my ego! I hope people can’t tell [laughs].

Have you learned anything about your own work from the critics, curators and theoreticians who have dealt with your work?

No. If I talk to a friend who tells me what he thinks, that’s great. But I don’t like listening to people whose profession that is. I appreciate normal people, normal viewers. Critics always try to prove to their reader that they’re smarter than the director…

The consensus is that you were part of a New Wave, and that your films, in one way or another, are part of a movement. Do you agree with that?

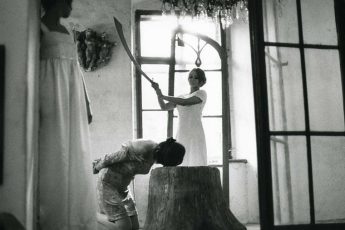

I’m happy I lived in a society together with Miloš Forman, Věra Chytilová, Ivan Passer, Jan Němec etc. It’s an honor, not because I like all of their films, but because they made some great movies and because they are honest filmmakers. Noone did nonsense, except for me. I did a commercial comedy in Germany because they payed me well, but I didn’t realise people would actually watch it. I don’t know, I don’t think Forman and these guys would do such a thing.

You’ve said in an interview that there is always some form of censorship that cinema has to face. Still, it seems that in Czechoslovakia in the 1960s, the apparatus gave artists a different sort of “impulse” than the state or system do today…

There were great films made under censorship, even in the United States, for instance when they were not allowed to show kissing. Freedom has this unlucky side effect that by making everything possible, you lack purpose and a direction. Creation always needs limits. If you’re writing a book, you’re composing a song, or directing a film, you have to make it. Creation comes out of conflict. If you don’t have borders, you babble nonsense. Of course, there are different sorts of constraints: even money is one. Every director working with any budget needs to adjust his vision to his budget. Or you have a vision that can’t be visualised the way you imagined. It’s all about conflict. Finally, there’s ideology, which goes through history like a red thread. There were taboos, rules passed on by church. Now that people are free, this freedom is problematic. It’s like when a young boy who wasn’t allowed to smoke and play cards leaves home: he will think that freedom lies in smoking and playing cards. That’s wrong. Until you grow up, your parents shouldn’t allow you to smoke or play cards.

You can artificially set rules and constraints, like the dogma movement.

Yes, but that’s formal. It’s a limit that provokes and inspires, because you have to find ways to overcome it, but it’s about the language, not the content. The main thing is to think about what effect you are going to have on the viewer. Many dogmatic films are quite depressing.

Can’t filmmakers in today’s world world also “grow up” and find the limits of our freedom?

Another question is who’s gonna watch that. In Czech cinema, the succesful are those who always try to discredit others. I think right now, we’re making some honest documentaries. That’s where our strength and future lies, even if the audience is limited right now. Feature films vary formal parametres, but documentaries are really straightforward. It’s easy to find a motivation to make feature films: you travel around festivals and get a lot of exposure, but documentaries are different. Many documentaries are made because they need to be made.

Thank you for the interview.

Leave a Comment